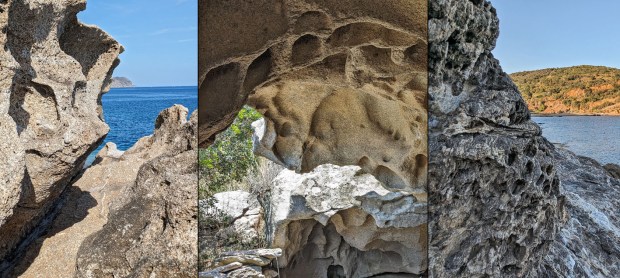

Tafoni at three sites on Elba: Spiaggia della Calle, Monte Capanne and Terranera. Photos by Per Storemyr

Together with Corsica and Sardinia, the Mediterranean island of Elba is a classical location for tafoni weathering. On a recent trip, I made some observations of tafoni forms and weathering activity, especially in the young Monte Capanne granite that makes up the western tip of the island. Large-scale tafoni, often forming small caves and shelters, prevail at higher altitudes as “relict” features with generally low current weathering activity. Some of the features are likely very old, initially developed in the Pleistocene. Simultaneously, tafoni weathering rates now appear high just by the shoreline, presumably governed by sea salts. Understanding the development of tafoni is difficult, and we need to look at geological history, as well as long-term climate and landscape development to approach it. This article offers a glimpse of tafoni at three sites on Elba, humble attempts at interpretation – and many questions.

Tafoni

Tafoni was first described on Corsica and in other parts of the Mediterranean in the late 19th century. The Norwegian geologist Hans H. Reusch was probably the first to use the term in scientific works, after a travel to Corsica in 1876, where he found tafoni not only in granite, but also in schist (Reusch, 1879, 1882). It is, however, a world-wide phenomenon, characterised by small and large-scale cavernous, alveolar and honeycomb weathering forms, that typically, but by no means exclusively, develop in coastal and hot or cold arid zones. Tafoni may form in stages, from incipient honeycombs that successively merge to larger ones and produce “caves” with concave walls, which upon further weathering can partially or entirely collapse.

Not restricted to granite, a wide variety of lithologies may become affected by tafoni, including other magmatic rocks (e.g. gabbro), volcanic rocks (e.g. basalt), sedimentary rocks (e.g. sandstone) and metamorphic rocks (e.g. gneiss). Globally, tafoni formation is a significant contributor to weathering and erosion of the earth’s landmass.

The mechanisms of formation, not least the peculiar forms, are not fully understood. Recent research suggests a range of explanations for the forms, with inspiration from universal laws of geometry to self-organization principles in nature. However, it seems that salts play a pivotal role in the actual weathering. As in other forms of salt weathering, this implies that internal (in the rocks themselves) and/or external salt sources must be present, the latter via transportation by wind and various forms of moisture. Moreover, the climate must be able to facilitate periods of significant salt action, such as crystallisation upon evaporation of moisture. Usually, this means that the environment must feature some form of aridity, either generally or seasonally, e.g. in the form of dry spring weather, in addition to more frequent changes in humidity and temperature.

In addition to salt, a range of chemical, biological and physical weathering agents may be at work, depending on the actual environment. And, as always in weathering, the properties of the rocks are of crucial significance for how – and how fast – the development of tafoni proceeds, if it takes place at all. This includes geological history and former weathering/alteration phenomena, for instance deep chemical weathering, as well as, more generally, mineral assemblages, textures and structures.

For references to tafoni research, read more at www.tafoni.com and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tafoni

Impressions of tafoni in different landscapes, from Jordan, via Corsica and Spain to coasts in Northern Europe. Drawings by Hans H. Reusch 1879, photos by Per Storemyr.

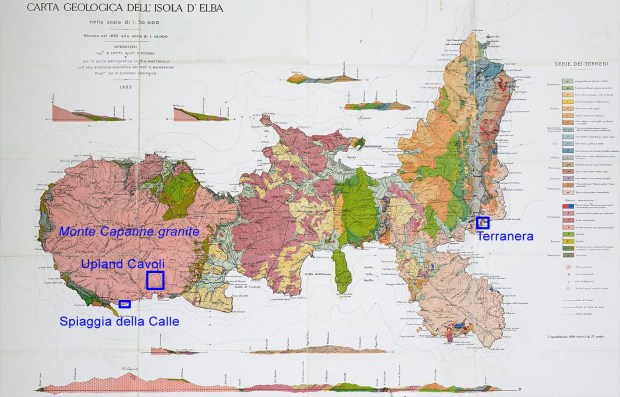

An early geological map of Elba (1885) with locations studied in this article marked. The map can be viewed at the mindat.org website. For comparison, see the newest (2016), detailed map of Elba here.

The Monte Capanne granite landscape

The finest tafoni on Elba can be observed in the Monte Capanne granite. It is a young granite, from the final stages of the Apennine orogeny and the shaping of the Mediterranean as we know it today. The pluton started intruding through a cover of sedimentary rocks in the Late Miocene, some 6-7 million years ago, due to extensional stress in the Tyrrhenian Sea (Bortolotti et al. 2001, Bortolotti et al. 2016).

The final uplift of the pluton took place only 4-2 million years ago, just before the onset of the Pleistocene. This suggests that Monte Capanne, now at 1019 m asl (above sea level), has developed its current morphology mainly during the shifting cold and warm climate episodes of the Pleistocene, with cold periods featuring periglacial conditions at higher altitudes, and sea levels up to 120 m lower than at present. Unlike neighbouring Corsica, with mountains more than 2700 m high, there are no traces of Pleistocene glaciers on Elba (Guglielmin 2022).

With a diameter of about 10 km at sea level, Monte Capanne shows steep ridges, valleys and ravines running from the top of the dome-shaped pluton. Screes filling valleys and slopes are common at higher altitudes, where the granite is intensely cracked. Boulder fields prevail along much of the slopes of the mountain, where – more generally – Pleistocene and Holocene landslide and slope deposits are common. High cliffs are the main landforms directly by the coast, intercepted by beaches at the end of valleys (Aringoli et al. 2009).

With the present climatic regime (warm, dry summers and cool, humid winters), the vegetation is now typical Mediterranean. Along the southern slopes of Monte Capanne, where my observations of tafoni have been made, the bedrock and boulder landscapes is characterised by shrubland, with threes such as Mediterranean Stone Pine in the lower reaches only.

The southern slopes of Monte Capanne. Photos by Per Storemyr

Petrography and use of Monte Capanne granite

The Monte Capanne granite is light grey in colour and described as a monzogranite or granodiorite. There are several facies, but generally the granite is medium-grained and mainly contains quartz, plagioclase, K-feldspar and biotite, with orthoclase commonly forming megacrysts up to 10 cm in size. It regularly also contains smaller and larger mafic enclaves (Bortolotti et al. 2016). As the main iron-containing mineral, biotite provides “rust” on alteration, which gives the colour and especially the weathering rinds of the granite a characteristic brownish tint.

According to observation, the granite does not seem to have been extremely influenced by deep weathering phenomena (saprolite formation). However, significant chemical weathering must have occurred along fractures, enabling the development of the present landscape with free, spheroidal boulders along the slopes (Aringoli et al. 2009). Moreover, in comparison, analysis of a very similar granite of the same age on the neighbouring island of Giglio showed general formation of clay minerals from feldspars and biotite, apparently due to hydrothermal processes (Fratini et al. 2022). This may well be the case also at Monte Capanne. Combined with remains of deep weathering, this implies an increase in porosity and a decrease in weathering resistance. The rocks are, in effect, not entirely “fresh”, a phenomenon that influences both tafoni development and weathering of architectural elements made form the stone.

Both the Giglio and Monte Capanne granites have been used extensively in architecture. The Romans operated significant quarries on the southern slopes of Monte Capanne, from where especially monolithic columns were extracted and shipped to e.g. Rome. The granite was priced among the Pisan builders of the Middle Ages. Many columns in the Pisa cathedral originate on Elba. And the stone is used everywhere in the villages on Elba itself, with quarries by San Piero still active (se overview at infoelba.com).

One of the reasons why the granite was so suitable for columns can be found in the sheeting joints of the granite and generally in the pattern of fractures and cleavage (cf. Aringoli et al. 2009), making it easy to split the rock by wedging. There are fantastic examples of splitting the rock to column forms along the southern slopes of Monte Capanne, near Cavoli.

Monte Capanne granite in the Grottarella quarries above Cavoli: From raw material to columns. Photos by Per Storemyr

Tafoni along the southern slopes of Monte Capanne

In the description to the “Geomorphological Map of the Tuscan Archipelago”, Aringoli et al. (2009) show tafoni on several islands in the Archipelago and give a summary of their widespread distribution at Monte Capanne. They indicate that the largest forms are found in a belt between 10 and 200 m asl, and especially in the southern, most arid slopes. The frequency of tafoni decreases with increasing altitude and they are seemingly rare above 500-600 m, where other weathering forms take over. But tafoni is generally so widespread at Monte Capanne, and with such weird forms, that they are the theme of the picture book “Mostri di pietra” (Stone monsters) by Nello Anselmi (2006). There are dragons, crocodiles and elephants, but also small caves and shelters formed by tafoni weathering (see also this YouTube video from the area around Madonna del Monte).

One of the pastoral shelters, “Capanna de Marco” at c. 300 m asl by Cavoli, offers a cool retreat from the baking sun. This is a large boulder, almost entirely carved out by tafoni, with a roof remaining at the top. Dry stone walls have been built along the sides to give maximum protection from sun and rain. Inside, where salts can accumulate, it is quite easy to see relatively active tafoni weathering, at places where honeycombs still exist. But on the whole and judged from the widespread presence of crustose lichen growth, also inside, the weathering rates appear low. Growth of lichen inside tafoni caverns was also observed by Aringoli et al. (2009)

Tafoni appearing relatively stable is also mainly the case in many other places on the southern slopes by Cavoli and Seccheto. Moreover, the general impression is that the formation of large-scale tafoni somewhat diminishes downwards to the sea, as more vegetation takes over. But this may, perhaps, also be a result of apparently fewer large boulders down-slope.

Obviously, many of the large-scale tafoni forms must be very old. This is supported not only by the sheer size and crustose lichen growth, but also by the fact that there is hardly any visible weathering in nearby Roman and Medieval stone quarries, i.e. on rock surfaces exposed to the elements for some 1000-2000 years.

The pastoral shelter “Capanna de Marco” near Cavoli is located in a big tafoni cavern. Photos by Per Storemyr

Impressions of old tafoni forms above Cavoli, many of which have lichen growth inside. Photos by Per Storemyr

Corsica comparison: Tafoni age and salt sources

With the lack of specific investigations at Monte Capanne, it is interesting to compare the tafoni with similar forms on Corsica. Though the granites are different (but both showing signs of deep chemical weathering), exposure ages inside several Corsican tafoni “caverns”, measured by cosmogenic isotopes (10Be), indicated that some surfaces had been stable for up to some 70 000 years, others in the range of 14-21 000 years (Brandmeier et al. 2011). This implies that the active weathering phases started thousands of years before.

Calculating the recession/weathering rates, it was also found that they, over the millennia, were lower in coastal areas than in the inland of Corsica. A somewhat opposite trend has been found on Sardinia. In current active tafoni weathering zones by the shoreline on Sardinia, the recession rates may be in the range of 20-30 mm/ka (mm/thousand years) (Guglielmin 2022).

Though comparison is always difficult, it would not seem far-fetched to consider many of the larger tafoni forms at Monte Capanne as developed in the Pleistocene. Guglielmin (2022) suggested that formation may originally have been triggered during cold and simultaneously arid periods, also with reference to current tafoni formation in Antarctica. Since tafoni has been found both below the current sea level and buried by Pleistocene aeolian deposits on Corsica and Sardinia, the Last Glacial Maximum may have been such a triggering period. However, it is not unlikely that triggering may also have taken place in hot and arid periods during interglacials – as indicated by the oldest exposure dates on Corsica (see above).

Brandmeier et al. (2011) also analysed salts involved in tafoni formation on Corsica. Sea salts (mainly halite) were only part of the picture, with sulphates apparently more important, and with gypsum and, to a lesser extent, sodium sulphates forming the actual salt types in action. Several sources for the sulphates were considered, including oxidation of small amounts of sulphides in the bedrock itself. However, based on isotope studies, wind-blown Saharan dust was interpreted as a major contributor. The sulphates in such dust originate from exposed evaporites in the desert. Saharan dust may, consequently, also be of importance as a salt source on Elba – in addition to bedrock sulphide and sea salts.

Tafoni and granite boulder landscape in Filitosa, Corsica. Photos by Per Storemyr

Tafoni on the southern shoreline of Monte Capanne

On the barren, steep and rocky shoreline of Monte Capanne, between the villages of Seccheto and Fetovaia (Spiaggia della Calle), weathering activity of widespread tafoni appear much higher than in the shrub-covered uplands. Weathering rates at this extremely exposed place by the open sea cannot be quantified without further investigations, but high speed is indicated by the combination of relatively big caverns and large amounts of small-scale honeycombs, often in the process of merging with one another. Aringoli et al. (2009) infers that small-scale honeycombs seem to be limited to the lower reaches of Monte Capanne, which is also my impression.

Like on Corsica, sulphate salts may well be in action, but there can be little doubt that sea salt is a very significant contributor to the weathering. This is indicated by lots of small, natural pools and conduits with loads of crystallizing halite directly by many tafoni features, up to some 20 m from the actual shoreline. The pools must be regularly filled in periods with high waves, since there are practically no tides in this part of the Mediterranean Sea.

There is no tafoni in a 10-metre belt on the sloping, wave-abraded, relatively smooth rocks just by the sea. Further up the slope, both “normal” salt weathering and tafoni gradually takes entirely over, with tafoni more prevalent along cracks and in steeper zones. Weathering is differential, in that megacrysts of orthoclase tend to stand out from the now friable and porous granite matrix. Moreover, mafic enclaves in the granite often weather faster. Approaching the steep coastal cliff with shrubs above, tafoni formation seem to diminish; perhaps due to – in the long run – processes like rock fall that disturbs evolution of tafoni.

Honeycombs and small-scale tafoni forms clearly dominate the picture. However, wherever larger boulders are present, they are usually heavily “eaten” by weathering from below. The normal, upward trending of tafoni formation, with concave “ceilings”, is also easily seen in much of the small-scale phenomena. My impression is that this is due to preferential accumulation of crystallising salts in this most sheltered part of the “caverns”. But the large-scale tafoni is not developed in the same way as in upland Cavoli. This is because the general salt weathering is so intense that no case-hardening can develop on the “outside” of boulders and small caves. Thus, it seems that tafoni forms collapse before they can grow big.

Though with ups and downs, the Mediterranean sea level and general climate has not changed very drastically over the last c. 4000 years (Vacchi et al. 2021). This is after the significant rise in sea level through the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene, following the melting of the ice caps since the Last Glacial Maximum. Thus, excluding possible neotectonics, it can be inferred that the current weathering regime at Spiaggia della Calle has been active for a few thousand years. It can also be suggested that weathering rates increased as the sea level rose, and the site came closer to the shoreline. Perhaps we are looking at a situation where an old tafoni landscape was somewhat “reactivated” in terms of weathering?

Tafoni weathering and general salt weathering at Spiaggia della Calle. Photos by Per Storemyr

Tafoni at Spiaggia di Terranera

Tafoni at Elba is not restricted to the Monte Capanne pluton, though this rather homogeneous lithology features the “finest” and most classical forms. They are also present in similar magmatic rocks (e.g. Porto Azurro monzogranite and Orano porphyritic granodiorite, see pictures in Anselmi 2006). Tafoni, especially in the form of honeycombs, has also been reported from loosely consolidated Pleistocene sandstone (dune deposits) near Capoliveri. In even less homogeneous rocks, for example by Spiaggia di Terranera by Porto Azurro in the SE part of the island, small-scale tafoni is also present.

Terranera features a complex geological sequence with Carboniferous schists intruded by Miocene aplitic dykes, Jurassic serpentinites, Cretaceous-Paleogene micaschists and Miocene breccia. A major fault system crosses the area, giving rise to intense brecciation and cataclasism (“crushing”). Moreover, the area is heavily mineralised with hematite, limonite and pyrite – it is one of Elba’s famous skarn iron deposits, mined from the Etruscan period to modern times (Garofalo et al. 2023).

The youngest sedimentary rocks, mineralised breccia and micaschists, are so friable that it is difficult to distinguish any tafoni among the general heavy weathering and erosion along the coastal cliffs. Presumably, salts produced from pyrite is an important contributor to the weathering. However, the oldest schists, more “sturdy” though still quite “crushed”, are dotted with small tafoni “holes” akin to honeycombs, with individual holes rarely exceeding 5 cm in diameter. This schist crop out in a limited, low-lying area by the shoreline only,

The holes occur practically everywhere in the schist, on vertical, sloping and even horizontal faces, but the white aplitic dykes are only little affected. When the holes merge, it typically takes place along the schistosity/foliation or along fractures. In places with much fracturing and “crushing”, tafoni seems, over time, to become indistinct. Hence, this may be a case where the rock’s structure strongly controls tafoni development and perhaps prevents the evolution of larger forms.

Without a deeper knowledge of the geological history, e.g. connected to the erosion of the former sedimentary rocks that once covered the schists, it is impossible to deduce anything about age and weathering rates. As for salt types, sulphates may be at work, but since the rocky outcrop is so close to the sea, halite is most certainly of importance, like in the reported case of Spiaggia della Calle (see above).

Impressions of geology and small-scale tafoni on Spiaggia di Terranera. Photos by Per Storemyr

A brief comparison with tafoni in Norway

The small-scale tafoni at Terranera has some resemblance to similar features in foliated rocks, e.g. some that I study along the southern Norwegian coast. There is quite a lot of tafoni in Norway, not least along the western coast (search “tafoni” in the geological heritage map of the Geological Survey of Norway). However, because of ice scouring during the Last Glacial Period, few large-scale forms have had the time to develop (but see Lund Andersen et al. 2022). In my study area, featuring Proterozoic banded gneiss directly by the southern Norwegian coastline, tafoni is thus generally small-scale and often restricted to the more easily weathered, darker (amphibolitic) bands. Structure also plays a significant role for the oval forms that often develop. When tafoni “holes” merge, it typically takes place along foliation and fractures, just like at Terranera.

In contrast to Terranera, the tafoni along parts of the southern Norwegian coast can be rather easily dated: By the city of Arendal, for example, the “fresh”, ice-scoured rocks along the shoreline rose from the sea only some 2000 years ago. Rough, preliminary estimates of weathering rates for these small-scale forms thus indicate that they are in the order of 10-50 mm/ka, in fact about the same as is currently observed along the coastline on Sardinia (see above).

Small-scale tafoni in Proterozoic banded gneiss on Tromøy, S-Norway, max c. 2000 years old. Compare with tafoni in schist on Spiaggia di Terranera. Photo by Per Storemyr

Questions

How tafoni develops on Elba appears to be dependent on many factors, such as lithology, landscape morphology, climate history, sea level change, availability of salts and so on. Above, I have tried to discuss what may be most important at three different locations. Each case study fills out the picture of the diverse nature of tafoni – and poses many questions:

- Upland Cavoli, Monte Capanne Miocene granite, altered by chemical weathering and probably hydrothermal processes: Mainly large-scale tafoni, which formation may initially have been triggered in one or more arid periods in the Pleistocene. Now activity is generally low, perhaps due to the current local climate regime, vegetation cover and growth of lichen? Maybe there is a more limited availability of salts than previously?

- Spiaggia della Calle along the shore, the same granite as in upland Cavoli: Seemingly very active weathering and many forms of tafoni, from honeycombs to caverns. General salt weathering is so intense that larger forms may rapidly collapse? Perhaps activity increased from some 4 000-5 000 years ago, as the sea by then had reached it approximate present level, implying an increase in the availability of sea salts? Moreover, perhaps an old tafoni landscape was “reactivated” as the sea moved closer?

- Spiaggia di Terranera along the shore, several lithologies, with small-scale tafoni in fractured Carboniferous schists: Loads of small tafoni holes, which development is seemingly strongly dependent on the structure of the rock, i.e. its schistosity and fracture system. How old and how active is it really?

Whatever the exact causes in each case study, tafoni is a very fascinating and beautiful phenomenon. Once interpreted and understood, it may tell us a lot about how different and changing climates influence rock weathering. Such understanding relies on climate records and detailed reconstruction of environmental history in the broad sense. It also relies on indirect and/or direct dating of the tafoni. Without dating, tafoni may remain in the realm of beautiful weathering forms only.

Cited references

- Anselmi N. 2006. Mostri di pietra e leggende dell’Isola d’ Elba. Bologna: Renografica edizioni d’arte. More info on Wikipedia.

- Aringoli D. et al. 2009. Carta geomorfologica dell’Arcipelago Toscano. Mem. Descr. Carta Geol.D’It., 7-107

- Bortolotti V. et al. 2001. The geology of the Elba Island: An historical introduction. Ofioliti, 26, 79-96

- Bortolotti V. et al. 2016. Geological map of Elba Island 1:25,000 Scale. Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research, ISPRA

- Brandmeier M. et al. 2011. New challenges for tafoni research. A new approach to understand processes and weathering rates. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms, 36: 839-852

- Fratini F. et al. 2022. The Alteration of Giglio Island Granite: Relevance to the Conservation of Monumental Architecture. Appl. Sci., 12, 4588.

- Garofalo P. et al. 2023. Fluid-rock interaction, skarn genesis, and hydrothermal alteration within an upper crustal fault zone (Island of Elba, Italy). Ore Geology Reviews, 154

- Guglielmin M. 2022. The Mediterranean Islands. In Oliva M. et al. (eds.) Periglacial Landscapes of Europe. Springer, 135-144

- Lund Andersen, J. et al. 2022. Rapid post-glacial bedrock weathering in coastal Norway, Geomorphology, 397

- Principi. G. et al. 2016. Carta geologica dell’Isola d’Elba. Scala 1:25.000. Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research, ISPRA

- Reusch H. H. 1879. Tafonier. Naturen: populærvitenskapelig tidsskrift. 3, 74-77

- Reusch H. H. 1882. Notes sur la géologie de la Corse. Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, 3rd series, 11: 53-67

- Vacchi M. et al. 2021. Climate pacing of millennial sea-level change variability in the central and western Mediterranean. Nature Communications, 12, 4013

Discover more from Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology & Conservation

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Tafoni blant jettegrytene på Kvaknes (Kilsund) | Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology & Conservation

Pingback: Tafoni-forvitring i skogsterreng på Flosta | Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology & Conservation

Pingback: The Grotesque World of Tafoni Weathering on the South Coast of Norway | Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology & Conservation

Pingback: Tafoni-forvitring på Sørlandskysten: Havets og landhevingens betydning | Per Storemyr Archaeology & Conservation