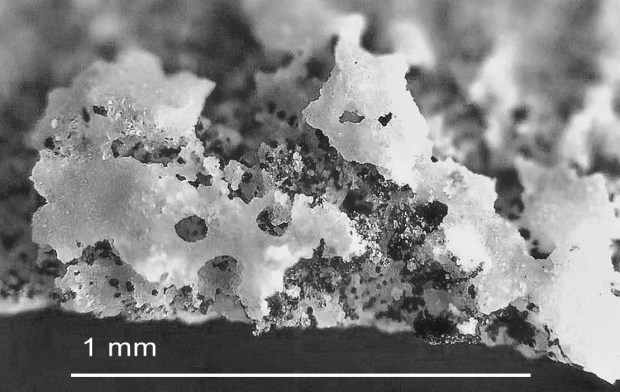

Borings in limestone fragment from Mljet, made by bivalves and likely broken from the littoral zone. Photo by Per Storemyr

As the final destination of our family’s road trip through Europe this summer, the Croatian island of Mljet offered a beginner’s crash course on bioerosion of limestone. My experience in weathering has mostly been connected to abiotic phenomena such as salt and frost weathering, so it was fascinating to observe the bizarre forms made by living organisms, especially in the littoral zone of the rocky coast. Particularly interesting is the boring into the limestone by bivalves, limpets, barnacles and several other organisms.

Karst and biokarst

The island of Mljet is located a little north of Dubrovnik. Like much of the Dalmatian coast of the Adriatic its geology is entirely made up of Cretaceous and Jurassic limestone and dolostone. Karst phenomena are widespread on this forested island and so is the formation of biokarst along the mostly very steep and rocky shoreline.

The forested island of Mljet seen from Veliki grad, the highest peak on the island (513 m). Photo by Per Storemyr

Mljet has a very rocky limestone coastline. From “Odysseus cave” on the south coast. Photo by Per Storemyr

Biokarst refer to the phenomenon of mixed biotic and abiotic weathering and erosion, or biologically enhanced dissolution or breakdown of limestone. It is prevalent on limestone coasts across the world and also contributes to accretion and sedimentation of new limestone. Simplified, an equivalent might be the dissolution of limestone in karst caves, which end up in the formation of stalactites and stalagmites.

Biokarst on the south coast of Mljet, with holes from boring organisms and very sharp limestone edges. Photo by Per Storemyr

But all this is very complex and there is a long range of organisms and mechanisms involved in the formation of biokarst. And wave-action is certainly also responsible for how the littoral zone looks like. This brief post touches the surface only.

At Mljet, I tried to photograph the most visible phenomena, notably boring into the limestone. The reason why e.g. shells bore into the rock is basically a hunt for food. Many of them feed on endolithic cyanobacteria, i.e. bacteria that colonise the interior of the stone, and also contributes to its dissolution/weakening. The boring itself is done by a combination of acid secretion and mechanical means (“teeth”).

Holes from boring organisms in the tidal zone at Mljet. Photo by Per Storemyr

Boring in the tidal zone

Tides are weak in the Adriatic, with Mljet experiencing only a few decimetres between highs and lows. Thus, narrow, more or less flat parts in the tidal zone are ideal for observing how organisms bore into the limestone.

Biokarst on a small platform in the tidal zone by Plaža Limuni on the eastern tip of Mljet. The rugged surface is overgrown by barnacles. Photo by Per Storemyr

The most visible and widespread activity that I observed was by barnacles. They adhere strongly to the rock surface, boring small and distinct, oval shaped holes. One hole doesn’t make much of a biokarst, but when hundreds and thousands repeatedly bore into the rock, they contribute to shaping a surface that becomes very rough, with sharp edges, pinnacles and pools.

Barnacles boring small, oval holes in the limestone. Note the removed barnacle to the right. Photo by Per Storemyr

Similarly, univalves such as the Common limpet bore circular, relatively shallow holes, with the shell perfectly adjusted to the periphery of the hole. Gastropodes are also found boring relatively shallow holes, sometimes adjusted so the whole shell fits well inside the hole.

Bivalves, on the other hand, bore several centimetres to decimetres deep tube-shaped cavities. I could only observe a few small bivales in action, but there are many larger, “fossil” holes, some of which includes remnants of the bivalve shells.

Boring shells. Top: Univalve, probably Common limpet, making shallow circles. Below left: Small gastropods (white) boring more irregular holes. Below right: Dead bivalve within a bored cavity. Photos by Per Storemyr

Then there is rock “peppered”, on a mm to sub-mm scale, with connected holes, caveties and “galleries”. Some sponges (Clionaidae) are known to make such patterns, but I don’t know whether this is what has happened in the cases I observed. Perhaps it is rather endolithic (cyano)bacteria that have been at work?

Limestone fragment looking like a sponge. Perhaps natural sponges created this pattern, or rather endolithic bacteria? Photo by Per Storemyr

Karst above the shoreline

Moving from the biokarst around the tidal zone, through the belt of black-coloured rock marking the influence of splash during high waves, other karst forms take over the barren landscape before the pine forest begins a little higher up.

Small platform with biokarst below black-coloured limestone affected by waves. Photo by Per Storemyr

Rugged limestone between the tidal zone and the forest. Photo by Per Storemyr

The black belt is probably to a significant extent covered by cyanobacteria and there are many signs of boring organisms. Higher up the barren zone, the limestone generally gets naturally white and there is very little vegetation. But the dissolution of the limestone is intense, typically featuring different karren forms, holes and pinnacles.

Karst between the tidal zone and the forest. Photo by Per Storemyr

Apart from the black belt, there is often little visible microbial activity in the barren zone, yet black and grey coloured patches are not uncommon, typically forming in depressions and cavities, and along cracks widened by dissolution. Looking closer, biopitting and similar sub-mm connected holes, caveties and “galleries” as mentioned above can be observed, nearly always with black microorganisms at the bottom, most probably cyanobacteria. Hence, it is likely that they are effectively “eating” the limestone. But it is also likely that “normal” dissolution plays a significant role in the karst formation in these barren zones.

Biopitting in linear arrangement. Width of image c. 50 cm. Photo by Per Storemyr

Microphoto of biopitting, showing “clean” limestone surface above, and organisms, probably cyanobacteria, in holes and cavities – and it areas “eaten” away. Width of image c. 10 mm. Photo by Per Storemyr

Close-up of biopitting, with the “clean” limestone above and myriad cavities with organisms, probably cyanobacteria, below. Photo by Per Storemyr

It is however not easy to be certain about the actual weathering and erosion mechanisms. As the rest of the Mediterranean the sea level in the Adriatic rose after the last ice age, but there have been local ups and downs due to neotectonics/earthquakes. This implies that it may be difficult to determine whether dry land by the seashore have been closer to or slightly under water in the recent past – and thus may have been affected by stronger bioerosion including borings.

*

Limestone is relatively weak, slightly soluble in water and full of carbon. It is rather easy to see bioerosion in such a rock – and to wonder about the effect it has in shaping whole coastlines. But bioerosion and bioweathering affect all types of rock in almost all environments. The impressions I got from Mljet was a strong reminder not to overlook the influence of life in studying all kinds of weathering and erosion phenomena. In addition, observing rock and life in the tidal zone is a reminder of the beauty of planet earth!

Beadlet anemone on top of barnacles in the tidal zone. Photo by Per Storemyr

Discover more from Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology & Conservation

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Bioerosion of shells on the beach – and in old Norwegian lime mortars | Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology & Conservation

Pingback: video: themenhirs of carnac

Hallo Per,

Beautiful phenomena, nice, clear photo’s, fine paper! I read it with great interest.

Greetings, Marian

Op do 21 aug 2025 om 14:25 schreef Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology &

Hi Marian, glad you liked it! Hope you are doing fine. Per

08/23/25

Per,

A great study in the milieu of limestone landforms and their related features from bioerosion and related agencies.

Thanks for sharing,

Jack Cresson

Thanks for reading!