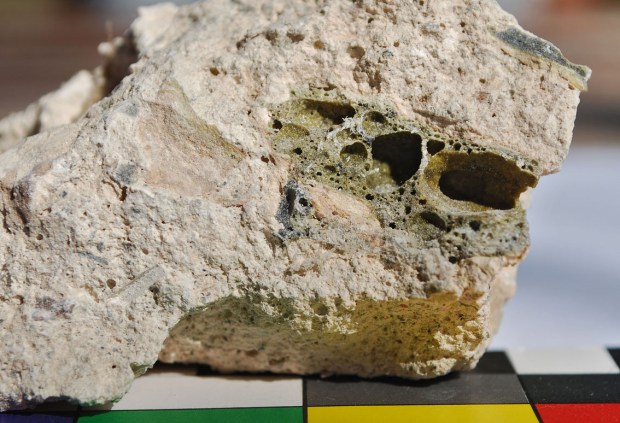

Slag in medieval lime mortar from the 12th century Hedrum church in Norway. Photo by Per Storemyr

During investigation of Hedrum church by Larvik in the winter of 2023, it was noticed that its hard, medieval lime mortars contained large amounts of slag fragments. By then it was not obvious whether the slag had been deliberately added, for example deriving from bog iron production, or whether it was naturally resulting from the burning of impure limestone at high temperatures. Subsequently, slag was discovered in medieval mortars at several other churches. Slag formation was also seen during contemporary, small-scale burning of impure limestone for restoration purposes. Hence, it became increasingly evident that “native” slag from the limestone itself is an ingredient not uncommon in old, Norwegian mortars. On further investigation and analysis, the significant hydraulic character of such mortars was moreover elucidated. This article discusses slag and other compounds and what effects they have on mortar properties.

Introduction

Deliberately adding slag to improve or change the properties of lime mortars has been a well-known practice in the early modern period. Both furnace slag and hammer slag have been used. Also, formation of crystalline slag during high-temperature burning of impure limestone is known, and often found in waste heaps by old lime kilns. Even when bigger pieces of such”native” slag is sorted out and dumped, smaller and larger fragments may inevitably end up in the mortar mix. Whereas the slag itself may (or may not) be rather inert, it is a strong indicator of high temperatures and also of the presence of associated burnt and sintered material (silicates) that render the mortars more or less hydraulic (cementitious). Examples of these phenomena are published in e.g. Swedish and Scottish contexts (Leslie & Hughes 2004, Johansson 2017, Lindqvist et al. 2019).

Piece of slag from burning of impure marble at Smilla limeworks (c. 1890-1940) in Hyllestad, West Norway. Photo by Per Storemyr

Even though many have seen slag by old lime kilns, formation of native slag from lime burning has not previously been reported from Norway. Thus, in this article three cases of medieval mortars containing slag and associated compounds are described. To back up the findings, observations of native slag formation during contemporary, small-scale lime burning are also reported. Analyses have been made using polarizing microscopy of thin sections and X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) of slag components.

Medieval churches described in this article. Photos by Per Storemyr

Churches sampled and lime burning carried out

Over the last few years mortars from about 12 Norwegian medieval stone buildings have been inspected visually and analysed with polarizing microscopy. Samples have been obtained during analyses of condition and practical restoration works. In at least three of these cases, the medieval mortars contain what is interpreted as native slag, as well as associated compounds that render the mortars hydraulic. The buildings include the near-coastal, 12th century Hedrum and Nøtterøy churches in Vestfold and the inland 13th century Ulnes church in Valdres. In addition, mortars from the ruins of Oslo Bishop’s Palace (13-14th century), St. Nicholas Church (Hadeland, 12-15th century) and Tingvoll church (Nordmøre, 12th century), are believed to contain native slag, but properties and context/dating are yet too ambiguous to include them in this article as clear examples of slag-containing, medieval mortars.

Parallel to the mortar analyses, small-scale lime burning has been carried out in new, intermittent wood-fired kilns with traditional design, recreating conditions favourable for producing native slag. Such conditions include raw materials of impure limestone and marble as well as sufficiently high temperatures, i.e. well above 850-900°C, which is necessary for calcination, but not for slag-formation. Several raw material types from known medieval lime burning regions have been burnt, of which the majority produced slag, slag-like and/or sintered components. Clear, crystalline slag was obtained form Silurian and Ordovician limestones from Porsgrunn (Telemark) and Ringsaker (Innlandet), respectively. Both are impure limestones from the Oslo Graben. Together with observations during the burning process, in this article also slaking, mortar mixing, and use of these limes are reported.

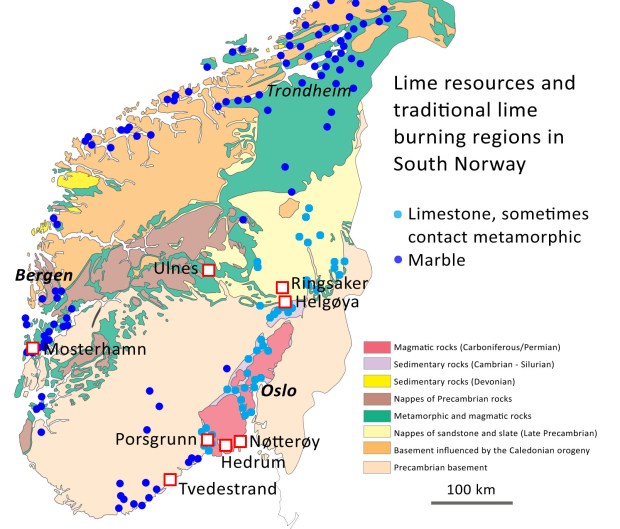

Geological map of South Norway with lime resources marked. These are indicative of traditional lime burning regions. Places mentioned in this article are marked with squares. Map and lime resources based on data from the Geological Survey of Norway.

Hedrum church

Investigations prior to restoration works in 2023-2024 established that the medieval parts of the nave in Hedrum church contained fat (c. 1:1 binder:aggregate), beige-brownish mortars. Added aggregates consisted of medium-sized grains derived from sand rich in feldspar, reflecting the local geology, with Permian intrusive, syenitic rocks (larvikite) of the Oslo Graben.

Deep within the masonry the mortars were firm, and a little harder than many other medieval lime mortars. But in the outer parts, below cement-containing repair mortars from the 1920s, they were unusually hard and extensively spalling, the latter clearly due to frost damages caused by the retaining of excessive moisture, not least by the impervious cement. After removal of these exterior repair mortars, exposing the medieval joint system in its entirety, detailed visual observation of the mortars revealed numerous small, dark grey and green slag fragments with rounded surfaces and voids/pores (see title photo above). Similar compounds were found in the mortar samples from deep within the masonry.

Medieval, hard and heavily spalled mortar from the nave of Hedrum church. Photo by Per Storemyr

Microscopy showed that the fragments often had a spinifex-texture and consisted of pyroxenes and melilite-group minerals within a glassy matrix. XRD confirmed this, detailing the pyroxene to augite ((Ca,Na)(Mg,Fe,Al,Ti)(Si,Al)2O6) and the melilite-group mineral to akermanite (Ca2Mg(Si2O7)), which – together with the glassy matrix and spinifex texture – are typical of calcium-rich silicate slags (see Leslie & Hughes 2004). The slag has a much higher calcium content than what is typical of the iron-rich silicate slags derived from traditional Norwegian bog iron production. Not including the less obvious phases, the amount of clear slag grains in the mortar is estimated at 10-15%.

There are also elongated, slate-like grains with melilite and other, unknown minerals, as well as many brown to dark, often elongated aggregates with a fine-grained character. Generally, these hard-to-interpret phases are likely representing altered, sintered and partially melted siliceous impurities in the limestone, typically thin slate fragments and intergranular mud.

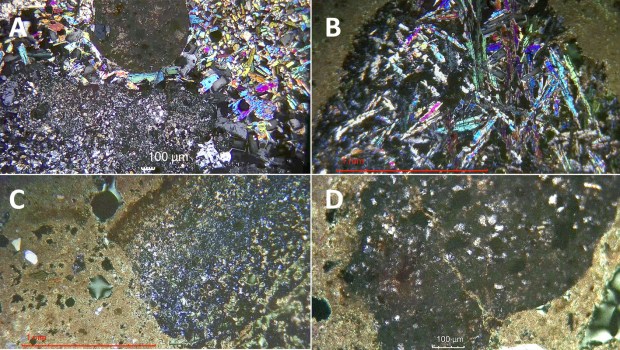

Microphotos of the Hedrum medieval mortars. Photos by Per Storemyr

The microphotos show distinct features of the Hederum medieval mortars: A) Slag fragments with pyroxene (colourful) and melilite (gray). B) Slag fragments with pyroxene with spinifex texture and some melilite in a glassy matrix. C) Part of burnt slate-like fragment with various components, gray represents melilite. D) Dark grain/aggregate from burnt impurities in the limestone. Crossed polarized light.

Possibly excluding the most crystalline slag-phases, the components likely contributed to a significant hydraulic set of the mortars. However, the exact hydraulic phases/clinkers remain unknown, as well as how these evolve over time. With the distinct brownish tone of the mortars, and of the binder under the microscope, it may be assumed that calcium aluminoferrites are important. Although some observations indicate the presence of dicalcium silicate (belite), no clear-cut evidence has been found under the microscope.

Obviously, these are very complex mortars, as compared to much simpler air-lime mortars based on purer limes. The complexity is, moreover, illuminated by the fact that they become much harder on long-term exterior exposure to excessive moisture (as compared to the situation in the core masonry only little influenced by moisture). It is likely that some clinker components continue to hydrate over very long timespans under moist conditions (such as belite may do). Perhaps the slag also acts as a pozzolan over time. Further, under the microscope the formation of much secondary (recrystallized) calcite and other, unknown precipitation products can be seen, as well as significant chemical etching of feldspar minerals in the aggregate. These phenomena are by experience known to contribute to strength/hardness of traditional mortars.

The provenance of the lime is unknown, and a few underburnt particles of limestone in the mortars are too small to give clear hints. However, there are no limestone deposits in the near vicinity of Hedrum church, thus limestone or quicklime had to be transported from sources farther away. The nearest are located in the Grenland district (Langesund-Brevik-Porsgrunn-Skien), some 30-50 km (by boat) to the west, where impure (and also rather pure) Ordovician and Silurian limestones can be found. These limestones have often undergone contact metamorphism because of their proximity to the Permian intrusive rocks of the Oslo Graben. Probably exploited since the Middle Ages, they are now used as raw materials in the cement industry (Heidelberg Materials, formerly Dalen Portland Cementfabrik).

Other possible sources are located about 90 km (by boat) to the north, in the Holmestrand district, where a significant lime industry prevailed until the early 20th century (see overview in Storemyr et al. 2023). In this context it is interesting to note that on experimental burning of this limestone in the late 1990s, much slag was observed associated with high-temperature areas in the kilns (information from Terje Berner, who built and operated the coal-fired, small kiln).

Nøtterøy church

Situated about 45 km (by boat) east of Hedrum, the medieval tower and nave of Nøtterøy church visually shows similar native slag components. However, the mortar stratigraphy is much more complex. On investigations in order to establish test fields for new conservation mortars in 2024, four joint mortar repair phases were found before the innermost and most likely original 12th century mortars were revealed. None of the more recent mortars had (visual) signs of slag.

Awaiting detailed petrographic analyses, visual inspection showed fat, light-beige mortars with medium to coarse sized aggregates and many pieces of charcoal, as were also seen at Hedrum, presumably from the lime burning. Microscopy of crushed slag showed elongated minerals in glassy matrices, partially with spinifex textures. Importantly, when not visually affected by excessive moisture, the mortars were firm but not hard. Visually, the amount of slag was lower than at Hedrum, indicating that the mortar is less hydraulic. However, in places with much recrystallized calcite, a sign of moist conditions, the mortar was significantly harder – harder than such recrystallization alone normally can account for.

The Nøtterøy masonry and medieval mortar with slag. Photo by Per Storemyr

Although the Nøtterøy mortar is generally softer, in principle we are probably looking at a situation quite similar to Hedrum, i.e. that the medieval mortars are based on burning of impure limestone, at temperatures high enough to produce native slag – and that the mortars have a tendency to harden over time. As for Hedrum, the provenance of the original limestone remains unknown, but with the Grenland and Holmestrand districts as prospective candidates.

Ulnes church

Ulnes church in Valdres, investigated in 2023-24, has medieval mortars both very different from and quite similar to Hedrum. The brown mortars are different because they are all very hard, both far within the masonry and in joints. Most of the mortars are also devoid of any added aggregate. They are similar because slag and associated compounds share many of the features found at Hedrum. The mortars are generally in very good shape and have not been exposed to excessive moisture over long time spans, a reason for which is that Valdres has a much drier climate than by the coast. And in contrast to Hedrum, where the lime plaster was stripped off in the 1920s, Ulnes has a relatively good plaster, and only few cement repairs.

The brown mortars were used as masonry and joint mortars in the 13th century chancel and partially in the nave, which was rebuilt in the 18th century. It seems that the medieval-style mortars were, at least to some extent, still used in the 18th century. It is mainly in these, younger mortars that some aggregate is present.

The Ulnes medieval mortars. Photos by Per Storemyr

It is hard to see slag in the Ulnes mortars by the naked eye. But under the microscope many small, porous fragments with melilite-group minerals and pyroxene with spinifex textures set in glassy matrices can be observed. Also, there are slate-like, elongated fragments consisting almost entirely of melilite. Conspicuous features include strongly brown, fine-grained aggregates as well as brown and dark grey, burnt slate fragments, often with alternating “bands” of lime. Moreover, the mortars are speckled with often large, brown fine-grained lime lumps. A few underburnt limestone fragments can be observed, either consisting of relatively large calcite crystals alone or smaller calcite crystals together with quartz, indicative of calcite-rich siltstone/quartzite. As in the Hedrum case, it is yet difficult to reveal exactly which hydraulic components that have been at work.

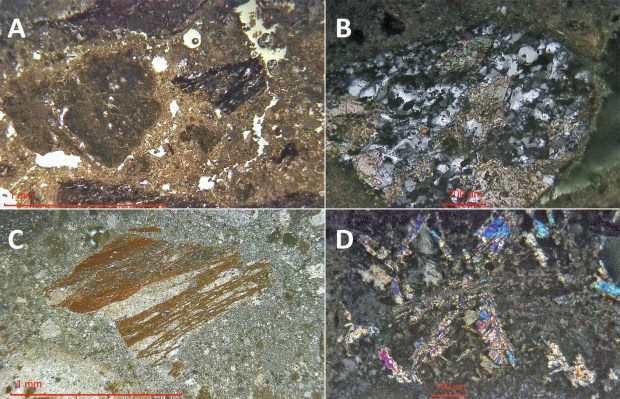

Microphotos of the Ulnes medieval mortars. Photos by Per Storemyr

The microphotos show distinct features of the Ulnes medieval mortars: A) Dark, hydraulic binder matrix, burnt slate-like fragments, and a large, half-rounded probably hydraulic lime lump. B) Underburnt sandstone/quartzite particle with calcite. C) Slate-like fragment with alternating bands of lime/hydraulic lime. D) Spinifex texture of slag fragment, with pyroxene (colourful) and melilite (dark grey) in a glassy matrix (black). Crossed polarized light, except A, which is in plane polarized light.

The reason why there is little or no added aggregate is very likely because burnt impurities that could not be slaked worked well as such. Adding gravel/sand would simply have made the mortar less usable from the perspective of the mason. Clear slags, slag-like fragments and brown/burnt slate fragments amount to some 20-30% or more of the mortars.

The content of the mortars points to the burning of very impure limestone or rather some kind of low-metamorphic calcareous slate/schist. Sources might be the nearest, very small deposits of impure Cambrian-Ordovician limestone interbedded with slate/schists and sandstone some 10-30 km east of Ulnes (especially in Nord-Etnedal). This region is historically known to have been a tiny lime burning district for mainly home use, with small kilns operated at summer mountain farms. Notably, it is reported that the lime burners had problems with the impure nature of the limestone/quicklime, and they often needed to use a sieve to get rid of impurities (Hermundstad 1965).

If this really is the source of the Ulnes lime, it is interesting because it would then show how traditional, local materials may have been used over long timespans in a region some 70-80 km (by sledge/waggon and riverboat) away from the nearest major lime producing area, at Toten.

Burning impure Porsgrunn silurian limestone in a small wood-fired intermittent kiln in Tvedestrand in 2023. The top cover is removed on ending the burn, leaving the kiln to cool down overnight. Photo by Per Storemyr

Slags from contemporary small-scale lime burning

Although the slags found have clearly not been deliberately added from any metal-production source (iron bloomery slag, hammer slag), there is a slight possibility that they may have formed from clay mortar linings in limekilns. That is: if real kilns were indeed used, and not the perhaps more likely – in the Middle Ages – simple heap or clamp “kilns”, which do not require any mortar whatsoever.

Slags formed from clay mortar linings in high temperature areas of traditional, intermittent stone-built wood-fired kilns are typical and have been experienced by the author many times. However, if not deliberately collected from the walls or bottom of the kiln on ending a firing cycle, there is little chance that it can enter the slaking/mortar mixing procedures in such quantities as in the Hedrum and Ulnes cases. Therefore, and also because of the strong presence of associated, burnt siliceous compounds, it must be concluded that impure limestone is the source of the slags reported.

It is evident that high temperatures are needed to form slags, but also that kiln temperatures in the Hedrum and Ulnes cases must have been quite variable. This is because, especially at Ulnes, underburnt limestone fragments are present. Variable temperatures are, naturally, very typical in traditional kilns.

But what temperatures are really needed to form the crystalline slags observed? Leslie & Hughes (2004) indicate that melilites need 1300-1350°C to form. However, given the complex nature of impure raw materials comprising components that may reduce formation temperatures (including calcium oxide) they propose that formation may also take place at lower temperatures, and conclude that well over 1000°C is needed in practice.

This is in line with observations from burning lumps of fossil-rich Silurian, partially contact-metamorphic limestone from Porsgrunn (the Bjørntvedt quarry), containing a little more than 70% calcium carbonate. In a new, half tonne intermittent kiln built in Tvedestrand, running slag formed in the lower reaches of the kiln on burning this limestone in 2023. Temperatures were not recorded, but from experience (comparison with other burns that included temperature measurements) and the fact that the clay-lined walls of the kiln were not excessively sintered, it was estimated that they must have been 1100-1200°C (see report on this website).

Similar temperatures seem to be needed for the formation of slag from impure, Ordovician Orthoceras limestone from Ringsaker, estimated at also containing some 70% calcium carbonate. Burning lumps of this stone has been carried out several times over the last few years, in new, c. 10 tonne traditional intermittent kilns at Helgøya and in Mosterhamn (for the latter, see report on this website). Slags easily form in the lower reaches of these kilns, so easily that it is estimated that temperatures probably have not been much above 1100°C.

Slag developed in the lower reaches of the kiln on burning Porsgrunn limestone. Photo by Per Storemyr

Slags from burning Ringsaker ordovician limestone. Photo by Per Storemyr

Calcium-rich slags in the burnt Porsgrunn lime contain pyroxenes (diopside and enstatite), as well as a K-Al-silicate (XRD), partially with spinifex textures (microscopy of crushed materials). Whereas melilite-group minerals are lacking, they are present as akermanite in the burnt Ringsaker lime, which additionally contains wollastonite (CaSiO3), a Mg-Fe-silicate and siderite (Fe-carbonate). The slight deviation from the Hedrum and Ulnes slag samples is likely reflecting varying types of silicate minerals present as impurities in the different limestones as well as burning temperatures.

It is very important to note that slags do not form in the higher reaches of such traditional kilns. The temperatures are too low, but sufficient for calcination and, according to experience, usually also for formation of some hydraulic compounds. The varying temperatures in traditional kilns is a key explanation why mortars in old buildings sometimes may have highly varying properties, though the binder may stem from the same limestone.

Experience from mixing mortars with slag-containing quicklime

The burnt slag-containing quicklimes produced in the contemporary kilns were far from dead-burnt, implying that it was quite easy to make workable mortars, but of course not from lumps with excessive amounts of hard slag.

A simple, well-known way of making nicely workable mortar mixes from these limes is by traditional, rather dry hotmixing, covering the lumps of quicklime with a little sand and sprinkling carefully with water to achieve as high slaking temperatures as possible. If there are many components that cannot be slaked, implying that added sand is not needed for a good mix (cf. the Ulnes case above), slaking can be speeded up by adding a lump or two of air-lime (or the purest pieces from the actual burn). This will quickly raise temperatures, usually setting off a “chain-reaction” in slaking the mix. It may be more efficient than using hot/boiling water.

Mortars from the most impure of these mixes set quickly and usually become very hard, too hard – too hydraulic – for application in normal, contemporary restoration work. Only time will show how they develop in test fields over the years to come.

However, lumps burnt at lower temperatures, e.g. sorted out from higher reaches of the kilns, have been used with some success in restoration works, at places where it was considered appropriate to apply such hydraulic mortars. According to experience, and in terms of firmness and carbonation speed, they behave quite in line with modern, medium (to weakly) hydraulic limes. But also in these cases, it remains to be seen how the mortars will develop over time.

Impressions of Ringsaker limestone, with mortars based on burning this stone at higher and lower temperatures.

Medieval diversity

Having established the properties of the native slag components and that they may form at 1100-1200°C, much more analytical work is needed to determine the actual clinker compounds responsible for the hydraulic nature of the mortars discussed.

Is it the typical calcium silicates (belite, alite?) and calcium aluminoferrites that are formed in the kilns, or are other compounds formed and available for hydration? Which compounds are responsible for increasing strength/hardness over time (such as in the Hedrum case)? Are the slags acting as pozzolans over time? Or are they merely indicators of high kiln temperatures?

However, the findings show that medieval lime mortars may be very diverse, indeed. The properties of the investigated limes and mortars are different from soft air-limes, which were probably less common in medieval Norway than often anticipated. Most medieval limes may have varying degrees of hydraulicity, all the way up to very strong mortars with slag, such as in the Ulnes case.

Traditional lime burning took place in hundreds of kilns in almost every corner of Norway, from the Middle Ages on, at nearly all places with available, often impure lime resources (Storemyr et al. 2023). Hence, it is only natural that the limes got their specific local and regional characteristics. Ultimately, they reflect the diverse limestone and marble geology of the country.

Acknowledgements

Sampling of mortars have been carried out by the author, as part of the Fabrica team together with Morten Stige. This has been done during wider investigation/consultancy work funded by local church authorities, with permission from the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage. The author has been responsible, together with colleagues, for small-scale lime burning in Tvedestrand and Mosterhamn. Tore Granmo is the responsible lime burner at Helgøya. XRD analyses were carried out by Calin Steindal at the University of Oslo. All microscopy is by the author.

Many people have helped, thanks in particular to Tore Granmo (Hamar/Helgøya), Anders Oppegaard (Tvedestrand), Bent Morten Steinsland (Mosterhamn), Martin Mannhart (Hedrum), Stig Aarøe Arnesen (Hedrum, Larvik church authorities), Daniel Bjørnstad (Nøtterøy, Færder church authorites), as well as Aud-Karin Hovi and Øyvind Huset (Ulnes, Nord-Aurdal church authorities).

The findings in this article was presented at the 2024 conference of Nordisk Forum for Bygningskalk (Nordic Building Limes Forum) in Aalborg (DK), 3-5 October 2024. See presentation, PDF in Norwegian

Sources

Reports from on-site investigations and mortars analyses are with the respective church authorities. References mentioned in the text are:

- Hermundstad, K. 1965. Industri i Valdres. I Valdres bygdebok, 5.2: Næringsvegane. Valdres bygdeboks forlag, 397-455. https://www.nb.no/items/48b24d263ba89a9036fb34f8ba1bb638?page=407

- Johansson, S. 2017. Hydrauliska bruk i Norden – från 1000-talet till nutid. Slutrapport postdocforskning. Byggkonsult Sölve Johansson AB, 54 p. https://www.bksjab.se/media/docs/Slutrapport2-1-postdocBildHems1702.pdf

- Leslie A.B. & Hughes, J.J. 2004. High-temperature slag formation in historic Scottish mortars: evidence for production dynamics in 18th–19th century lime production from Charlestown. Materials Characterization, 53, 181– 186

- Lindqvist, J.E., Balksten K. & Fredrich, B. 2019. Blast furnace slag in historic mortars of Bergslagen, Sweden. Proceedings of the 5th Historic Mortars Conference. RILEM Publications, 585-595. https://www.academia.edu/42315574/Blast_furnace_slag_in_historic_mortars_of_Bergslagen_Sweden

- Storemyr, P., Granmo, T. & Berner, T. 2023. Småskala kalkbrenning. Geologisk mangfold i kulturminnevernets tjeneste. Fortidsminneforeningens årbok, 177, s. 53-76. https://per-storemyr.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2023-storemyr-granmo-berner-smaskala-kalkbrenning-fortidsminneforeningens-arbok.pdf

Discover more from Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology & Conservation

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

10/07/24 Thanks for the latest data and experiments in (who knew?) the diversity of ancient mortars developed in Norway. It looks like this could be another great attribute in defining techniques and materials across all parts of Scandinavia. J. Cresson

Thanks a lot for your interest!