The Sparsås soapstone quarry in Aust-Agder, with carved out vessel blanks attached to the bedrock and highly organised spoil heaps in the background. Photo by PS

The region of Aust-Agder in Southern Norway hosts a range of Iron Age soapstone vessel quarries. One of them, the Sparsås quarry in Froland, is exceptionally well-preserved and one of the most “classic” quarries I have ever visited in Norway. With unfinished vessel blanks still attached to the quarry faces and a highly organised layout of the spoil heaps, it once must have been worked in an efficient way, providing vessels and other items for regional use and, quite probably, for export to Denmark and beyond. Here’s an account of the research history, geology and layout of the quarry summarized in a hypothesis offered: This was a short-lived quarry, operated for a generation or so within the 9th or 10th century CE. A peculiarity – that the quarry may also have been used for minor production of millstone – is moreover interpreted.

Sparsås, locally named Grytefjellet (“Pot Mountain”), is one of about 10 soapstone quarries in Aust-Agder. Located in the municipality of Froland, between Nelaug and Heldalsmo, 30 km from the Skagerrak coast, it stands out as extremely well-preserved and there has been no visible interference by modern exploitation.

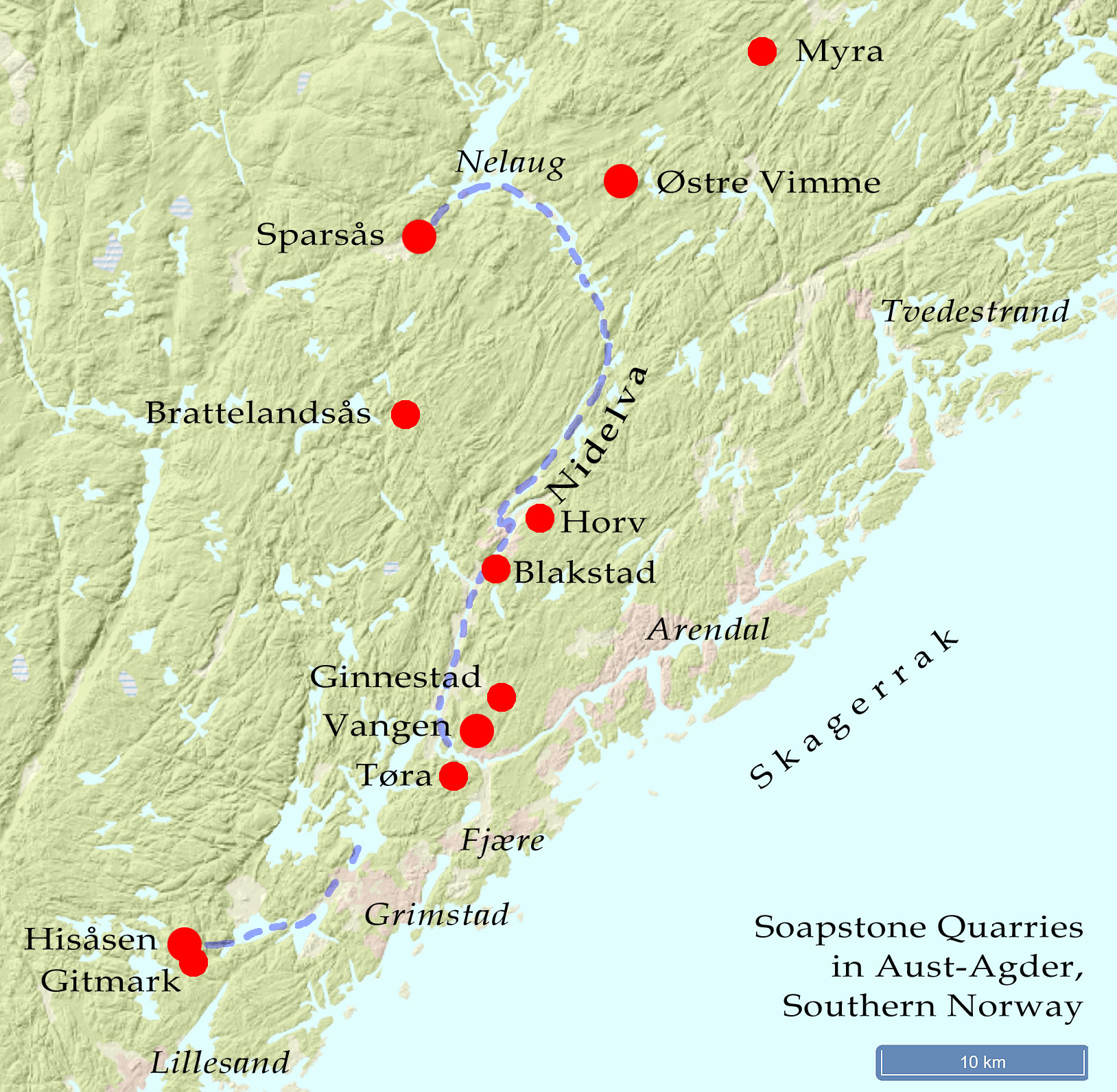

Overview of soapstone quarries in Aust-Agder, with main transportation routes indicated. Map based on Kulturminnesøk and NGU’s mineral resource database

Research history

The research history is sparse. Archaeologist Helge Gjessing visited the quarry in 1922 and offered a short description in a regional overview of the prehistory of Aust-Agder (Gjessing 1923), in which he underlined the vessel extraction marks and spoil heaps. He inferred that the workings could have been rather deep and observed quite a few half-worked, abandoned vessels. Gjessing’s work at Sparsås, and descriptions of other soapstone quarries in Froland, are also featured in Froland bygdebok (Dannevig 1979).

Gjessing briefly mentions the observation of a broken quernstone (probably a small millstone) in the quarry, its whereabouts now unfortunately unclear. A millstone extracted in a soapstone quarry sounds strange due to the softness of soapstone. But it is not as odd as it seems, as will be discussed below.

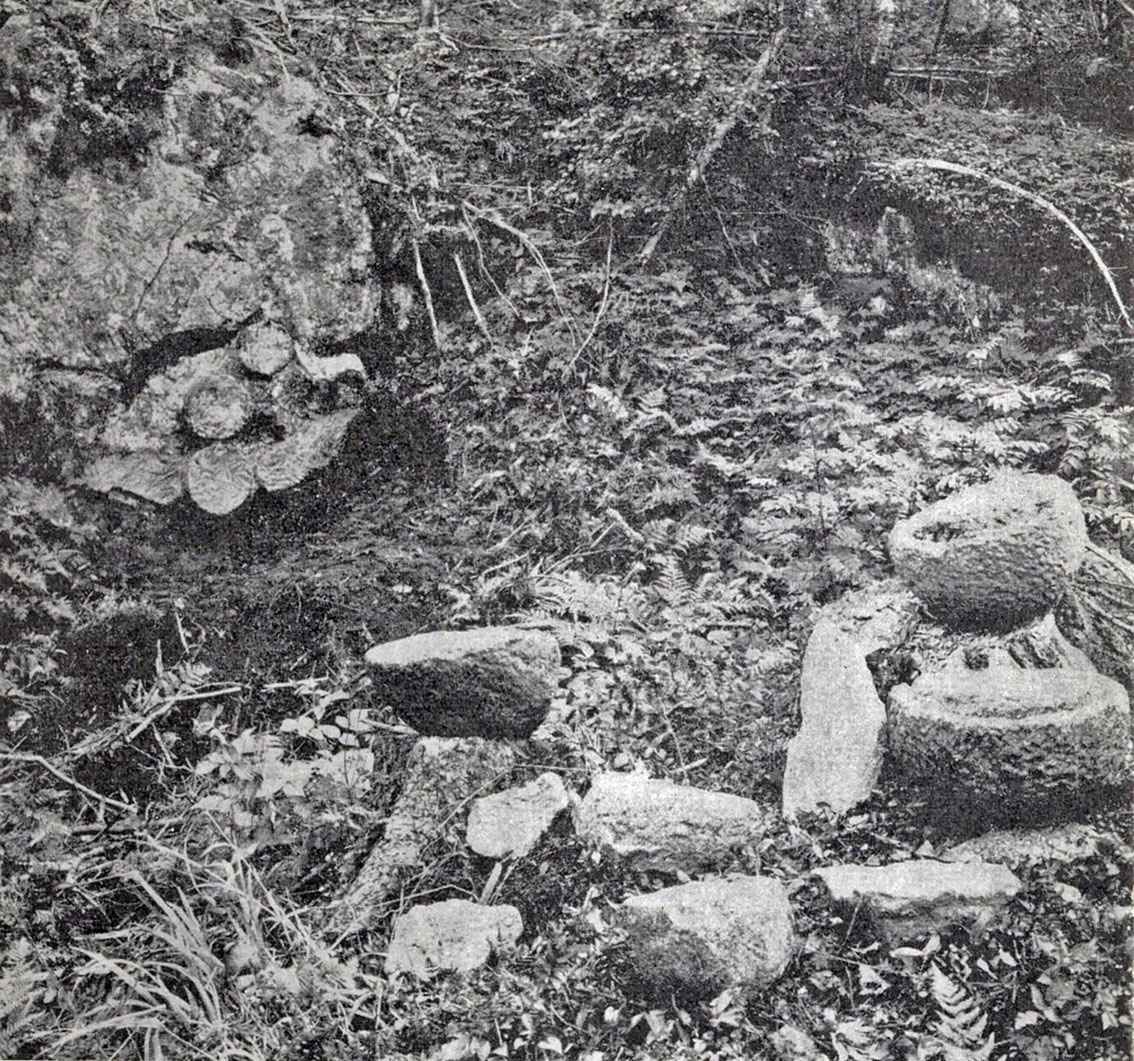

A small part of the Sparsås quarry with finds recovered from the spoil heaps by Helge Jessing in 1922. Photo by Gjessing, from Skjølsvold (1961)

Archaeologist Arne Skjølsvold went to see the quarry in 1952. In his influential Klebersteinsindustrien i vikingetiden (“The Viking Age Soapstone Industry”) (1961), he points out that there are two quarries of similar size, both surrounded by organised spoil heaps and with many traces of vessel extraction on retracted rock faces.

He also observed a peculiar way of carving: Normally, vessel extraction in Norway (and elsewhere) was undertaken by carving the underside of the item before it was spilt from the host rock, implying that items abandoned due to e.g. cracks show the underside “sticking out”. Not so at Sparsås, where several vessel forms are carved with the upper side sticking out. In some of them, hollowing with the use of chisels (or picks) had commenced before the rough outs were abandoned.

From the consistent size and typology (R729, see also Schou 2017: 139) of half-finished, abandoned vessels, including those still attached to the host rock, Skjølsvold inferred that the quarry quite certainly was worked in the Viking Age.

Half-finished vessel recovered from the Sparsås spoil heaps. Photo by Kulturhistorisk Museum, University of Oslo. Retrieved from digitaltmuseum.no

In more recent times the quarry has attracted the occasional archaeologist, geologist and interested visitor, but as far as I know, there has been no further archaeological or geoarchaeological survey. The quarry is described in some detail in the Norwegian cultural heritage database (see Kulturminnesøk), but only briefly in the mineral resources database of the Geological Survey of Norway.

Several authors, including Låg (1999), Holberg & Dørum (2018), and in particular archaeologist Torbjørn Preus Schou, in his work on regional vessel production and trade (2007, 2017), have highlighted the significance of Sparsås and other soapstone quarries for understanding the Viking Age in Aust-Agder. Schou argues for professional craftsmanship (as Skjølsvold before him), the River Nidelva as a transportation route and the area of Fjære by Grimstad as a centre for trade in soapstone vessels, with export e.g. to Denmark, as well as to Kaupang. The arguments on export are highly interesting, indeed, but not based on geological provenance studies.

Recently, Skowronek & Chmielowski (2024) have also argued that vessels with a likely provenance in the Aust-Agder quarries, notably Hisåsen, were exported to Ribe (Denmark) and Hedeby (North-Germany) in the 9th and 10th centuries. Their work is also very intriguing, but based on indirect, geochemical provenance studies only, and not on analyses of soapstone from Hisåsen and other quarries in the region.

Geology

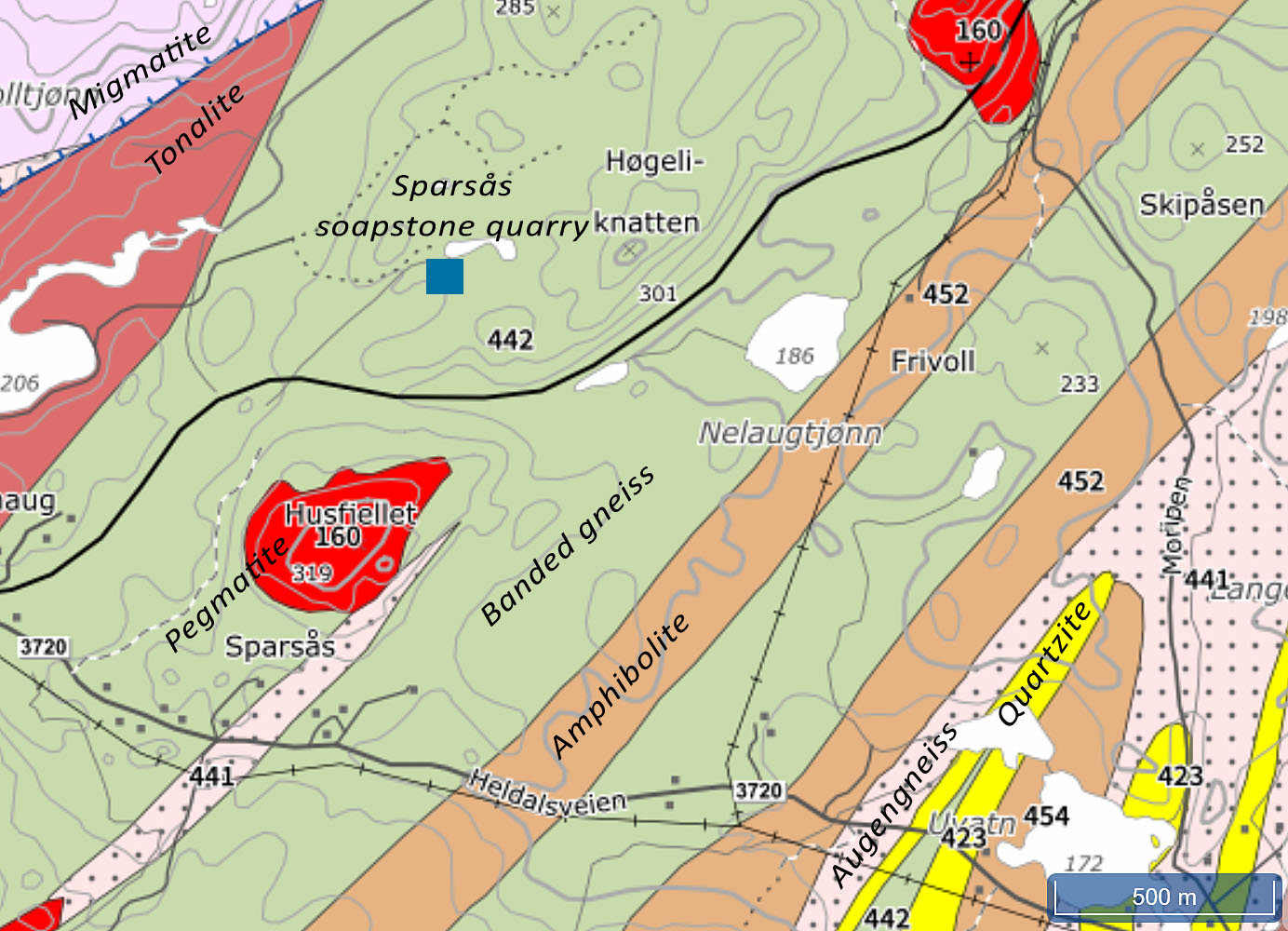

The Sparsås quarry is situated within the high-grade metamorphic Bamble Sector of the Norwegian Precambrian (review in Nijland et al. 2014). Whereas the local bedrock, with an age of about 1500 million years (Ma), is dominated by various quartz-rich gneisses, there are also amphibolite and metagabbro, as well as quartzite and some marble further away. Younger pegmatites criss-cross the area, also very close to the quarry, and are present as larger bodies a few hundred metres away. Moreover, Nijland et al. (2014) have observed a small ultramafic (dunite) lens by Nelaugtjønn, 500 m to the east of the quarry.

Local geology by the Sparsås quarry site. Map based on NGU’s geological maps

The soapstone in the quarry is different from the classical, light greyish, soft varieties, often with carbonate veins and aggregates, and often rather brownish from weathering. Such soapstone is especially found in the Norwegian Caledonides and usually derived via serpentinite from altered ultramafic rocks (see Storemyr & Heldal 2002 and several articles in Hansen & Storemyr 2017). Indeed, the Sparsås rock can hardly be called a soapstone, as it is visually almost akin to a dark amphibolitic rock. Since the rock is relatively soft, from the perspective of usefulness for carving items, it would be more correct to use the term veksten (weak stone), coined by Amund Helland in 1893. However, for the sake of simplicity, in this article I will continue to use soapstone.

Typical appearance of the dark Sparsås soapstone. Photo by PS

From visual inspection, the Sparsås rock is composed of amphibole, mica, talc (powder from rock smeary between fingers) and probably some quartz. Trace minerals include carbonate (slight reaction in 10% HCl) and magnetite (powder is drawn to magnet). This is a highly preliminary assessment but indicates a deviation from the classic Norwegian soapstone mineralogy with talc, chlorite and carbonate (+ minor and trace minerals). This said, with amphibole as “reinforcement”, the Sparsås soapstone is quite strong. It may not have been the easiest to carve, but on the other hand would have resisted mechanical impact of various kinds.

The relative softness of the stone, but with a content of much harder amphibole, may be the explanation why Gjessing (2023) observed a quernstone in the quarry (see above). This is the basic property of most historic quernstones/millstones, i.e. a soft matrix as well as spots of harder minerals, in Norway exemplified by the large, old quarry landscapes of garnet micaschist in Hyllestad and Selbu (e.g. Heldal et al. 2013). This rock was not suitable for vessel production, but there indeed exist historic sites, at which vessels and quernstones were produced from the same quarries. Valle d’Aosta in the Italian Alps is a most pronounced example, with a geology comprising soft chlorite schist dotted with hard garnets, exploited since Roman times (e.g. Storta 2023, and references therein). It is, however, unlikely that the Sparsås stone was particularly well-suited for quernstone. There would not have been much production of such stone, but the theme is definitely worth consideration in further studies.

From current knowledge it is hardly possible to interpret the geological origin of the soapstone. Frigstad (2004) suggested that most soapstone deposits in Aust-Agder have a gabbroic affinity. Skowronek & Chmielowski (2024) agreed with regard to the Hisåsen site, but implied that the other Aust-Agder deposits may have an ultramafic affinity. However, Moree & Nijland (1996) and Moree (1998) in their geological studies of the Østre Vimme soapstone quarry (just 10 km northeast of the Sparsås site), favoured enrichment of magnesium by metasomatic processes/skarn formation prior to regional metamorphism (the Sveconorwegian orogeny, ca. 1150-950 ma) as a viable way to explain the soapstone/talc formation. This is further discussed in a separate article on this website.

Østre Vimme has a surrounding geology not unlike the Sparsås site. But in addition to soapstone looking somewhat like the Sparsås rock, the quarry features a lot of very soft, talc-rich soapstone. Such talc-rich varieties have not yet been observed at Sparsås.

Quarry layout

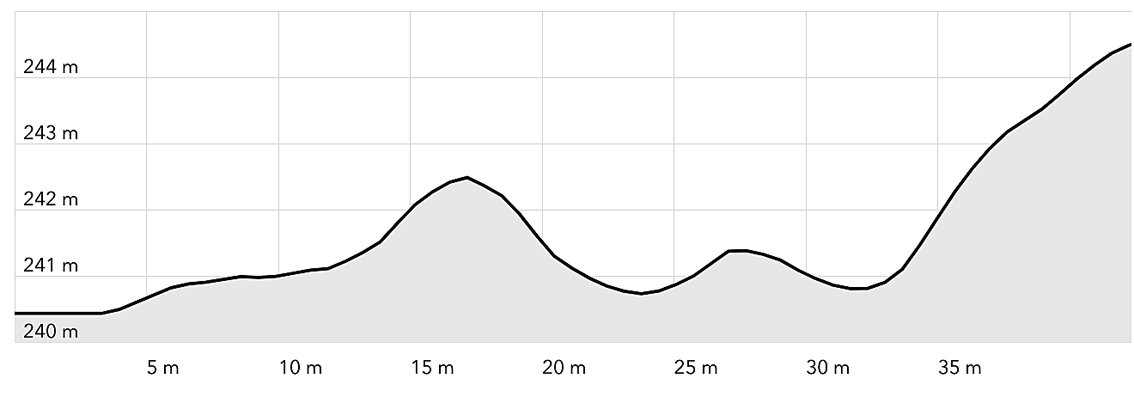

The two quarries at Sparsås are located at c. 240 m.a.s.l. in thick forest along the northern slope of a hill/ridge trending SW-NE, just south of a small lake called Moltetjønn and its surrounding moor. The quarries are some 40 m apart, each with a diameter of about 30 m, encompassing 3-4 pits, quarry faces and spoil typically deposited along the western margins of the workings.

Lidar elevation model of the two Sparsås quarries. From hoydedata.no

Elevation profile a-a’ (see map above). From hoydedata.no

Although the quarries are overgrown with moss, many circular vessel extraction marks are easy to spot. In quarry 1 they are concentrated on retracted, semi-vertical quarry faces, up to 2-3 m high, along the southern side. One of these quarry faces has detached from the bedrock and fallen over since Helge Gjessing visited the site a hundred years ago. The extraction marks feature half-finished vessels still attached to the bedrock, as well as circular marks from split/removed vessel blanks.

The main quarry face in quarry 1. Photo by PS

Naturally detached quarry face with vessel blanks still attached. Quarry 1. Photo by PS

Like quarry 1, quarry 2 is characterized by depressions indicative of deeper (now spoil, earth and moss-filled) workings within the encompassing spoil heaps. It is not possible to indicate their depth, but they will, presumably, have been rather quickly water-filled after abandonment of quarrying. There are just a few visible vessel extraction marks in the overgrown bedrock of quarry 2, but a large boulder is standing out in the SW-part (see title photo). It has many extraction marks, and a vessel blank in which hollowing has begun from the top.

Vessel blanks attached to the bedrock in quarry 2. Photo by PS

Vessel blank attached to the bedrock. Hollowing has begun. Quarry 2. Photo by PS

As the rather uniform extraction marks for individual vessels, the disposal of waste also gives an impression of uniformity, as the spoil heaps are generally very orderly placed at the periphery of the two quarries. They are rising to a height of 1-2 m above the current “quarry floor” and descending gently on the exterior side. There is no track in/out of the quarries, but an indistinct path between two spoil heaps in quarry 1 is leading in a westerly direction. Whether this is indicative of an ancient transportation route is uncertain.

Quarry 1 seen from above. Note the moss-filled depressions, indicative of deeper quarrying. Photo by PS

Survey within 100 m from the two quarries has not revealed further workings in the area. Also, no reports have been found indicating that the Sparsås site includes more quarries.

Spoil volume and production rate

From measurements using Lidar-maps, the spoil heaps of the two quarries cover a total area of roughly 500 m2 and have an estimated average height of about 1 m. This implies that the volume of the spoil heaps would correspond to a volume of 250-350 m3 of solid rock (for method of calculation, see Storemyr & Heldal 2017). Given that the vessels normally have a diameter of 30-35 cm and a height of up to 15-20 cm, in a perfect rock it would be possible to make up to 8 vessels from 1 m3. Rocks are not perfect and 4 vessels per 1 m3 is probably closer to reality. This would correspond to a waste rate of 90-95%, hence the total number of vessels produced may have been in the range of 1000-1500.

This, of course, is educated guesswork only. A waste rate of 80% or even lower would increase the number of vessels correspondingly. It is, however, my impression that we are not talking about many thousand vessels, but an upper limit in the range of 3-4000 vessels is perhaps not entirely impossible. At any rate an order of magnitude may have been established: more than 1000 vessels, and less than 5000. Let’s use a conservative 2000 for further discussion.

The type of vessels extracted (R729) are found at consumption sites in the 9th and 10th centuries, not least abroad (e.g. Skjølsvold 1961; Schou 2007, 2017; Skowronek & Chmielowski 2024, and references therein). Hence, a maximum of 200 years for a main phase of working the quarry may be assumed. This implies an annual production of 10 vessels.

However, with the uniform work that seems to have taken place, it is likely that the main production phase was much shorter. If, say, 50 vessel blanks were produced by a small team of experienced quarrymen each summer, and subsequently transported for pre-final carving/dressing at one or more local/regional centres/farms, we are looking at a period of 30-40 years only, i.e. one or two generation’s work in the two quarries. If more quarrymen were involved, we may be talking about a time frame down to a decade.

Indistinct path leading into quarry 1 between spoil heaps. Photo by PS

Hypothesis

A hypothesis has thus been established: Given the limited size, uniform layout and extraction marks, as well as very organised disposal of waste, the main phase of quarry work may have been over a generation or so in the 9th or 10th century CE. We may also ask: With the quarry’s uniformity and such a short lifespan, perhaps exploitation was a result of deliberate survey to find usable soapstone in a period of high vessel demand? For most soapstone quarries in Norway seem to have been quite long-lived with multiple production phases. This includes the nearest known neighbour to Sparsås – the Østre Vimme quarry – described in a separate article on this website.

To confirm or reject the hypotheses, more research obviously must be done on the quarry’s geology and archaeology, including radiocarbon dating, as well as comparison with other Aust-Agder quarries. However, the most intriguing work ought to be geological/geochemical provenance studies. For here we may have a short-lived quarry site with a seemingly special geology that did not give the typical, soft soapstone vessels. This could imply a favourable situation for tracing vessels possibly exported to Denmark and beyond.

Many thanks to archaeologist and stone artisan Morten Kutschera of the Agder County Council, with whom I visited the quarry in May 2024.

Last updated 6.1.2026

References

Dannevig, B. 1979. Froland. 1: Bygd og samfunn. Froland kommune

Frigstad, O. F. 2004. Kleberstein – en utstilling i Åmli. Agder naturmuseum og botaniske hage. Årbok 176, 28–33

Gjessing, H. 1923. Aust-Agder i forhistorisk tid. In Scheel, F. (ed.) Arendal fra fortid til nutid: utgit ved byens 200-aars jubileum som kjøbstad 7. mai 1923. Kristiania, 1-56

Grenne, T., Heldal, T., Meyer, G.B. & Bloxam, E. 2008. From Hyllestad to Selbu: Norwegian millstone quarrying through 1300 years. In Slagstad, T. (ed.) Geology for Society, Geological Survey of Norway Special Publication, 11, 47-66

Hansen, G. & Storemyr, P. (eds.) 2017. Soapstone in the North: Quarries, Products and People. 7000 BC – AD 1700. UBAS University of Bergen Archaeological Series, 9

Helland, A. 1893. Tagskifere, heller og vekstene. NGU, 10

Holberg, E. & Dørum, K. 2018. Arendal før kjøpstaden. Fram til 1723. Arendal by- og regionshistorie, bd. 1, Oslo

Låg, T. 1999. Agders historie. 800-1350. Agder historielag, Kristiansand.

Nijland, T. G., Harlov, D. E. & Andersen, T. 2014. The Bamble Sector, South Norway: A review. Geoscience Frontiers, 5, 5, 635-658

Moree, M. 1998. The Behaviour of retrograde fluids in high-Pressure settings. Implications for the petrology and geochemistry of subduction-related metabasic rocks from Catalina Island (California, USA) and Syros (Greece). PhD Thesis, Free University Amsterdam

Moree, M. & Nijland, T. G. 1996. The Vimme talc deposit: field occurrence, whole rock chemistry & Pb isotopes. In SNF excursion Numedal-Telemark-Bamble, 22-25 aug. 1996. Unpublished report

Schou, T. P. 2007. Handel, produksjon og kommunikasjon – en undersøkelse av klebersteinsvirksomheten i Aust-Agders vikingtid med fokus på Fjære og Landvik. Master thesis, University of Bergen

Schou, T. P. 2017. Trade and Hierarchy: The Viking Age Soapstone Vessel Production and Trade of Agder. Soapstone in the North: Quarries, Products and People. 7000 BC – AD 1700. In Hansen, G & Storemyr, P. (eds.), UBAS University of Bergen Archaeological Series, 9, 133-152

Skjølsvold, A. 1961. Klebersteinsindustrien i vikingetiden. Oslo

Skowronek, T. & Chmielowski, R. 2024. Geochemical constraints on the provenance of Viking Age soapstone finds from Ribe, Denmark. By, marsk og geest, 36, 4-21

Storemyr, P. & Heldal, T. 2002. Soapstone Production through Norwegian History: Geology, Properties, Quarrying and Use. In: Herrmann, J., Herz, N. & Newman, R. (eds.): ASMOSIA 5, Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone – Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference of the Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, June 11-15, 1998. London: Archetype Publications, 359-369.

Storemyr, P. & Heldal, T. 2017. Reconstructing a Medieval Underground Soapstone Quarry: Bakkaunet in Trondheim in an International Perspective. In Hansen, G. & Storemyr, P. (eds.), Soapstone in the North: Quarries, Products and People. 7000 BC – AD 1700. UBAS University of Bergen Archaeological Series, 9, 107-130

Storta E. 2023. Petrographic study of pietra ollare mills from Garda Civic Museum in Ivrea (To). Rend. Online Soc. Geol. It., 60, 112-124

Discover more from Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology & Conservation

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Gondwana, Laurasia, Tethys Ocean - Earth millions of years ago

Pingback: Soapstone in the Far South of Norway (II): The Østre Vimme Multiperiod Quarry With Very Soft Soapstone | Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology & Conservation