The ancient quarry floor of Østre Vimme soapstone quarry – below detached and fallen blocks. Photo by PS

Østre Vimme is another of the several old soapstone quarries in the Aust-Agder region of Southern Norway. It was worked in the Iron Age for «standard» vessels, but it has at least three production phases, for which there may be a specific reason: Parts of the quarry feature very talc-rich and soft soapstone, implying that the stone was also easy to carve for small items like spindle whorls, sinkers and lamps. Hence, it would have been a valuable resource for a long time. Softness may be the result of a special geology. Dutch geologists have suggested that this is a deposit not derived from alteration of ultramafic rocks, which is by far most common mode of formation in Norway. Rather, it may derive from alteration of dolomitic limestone. There is only on other known soapstone deposit in Norway with such an origin. Here’s an account of this exciting quarry, also including a discussion of whether soapstone vessels from the quarry were exported to Denmark in the 9th century CE.

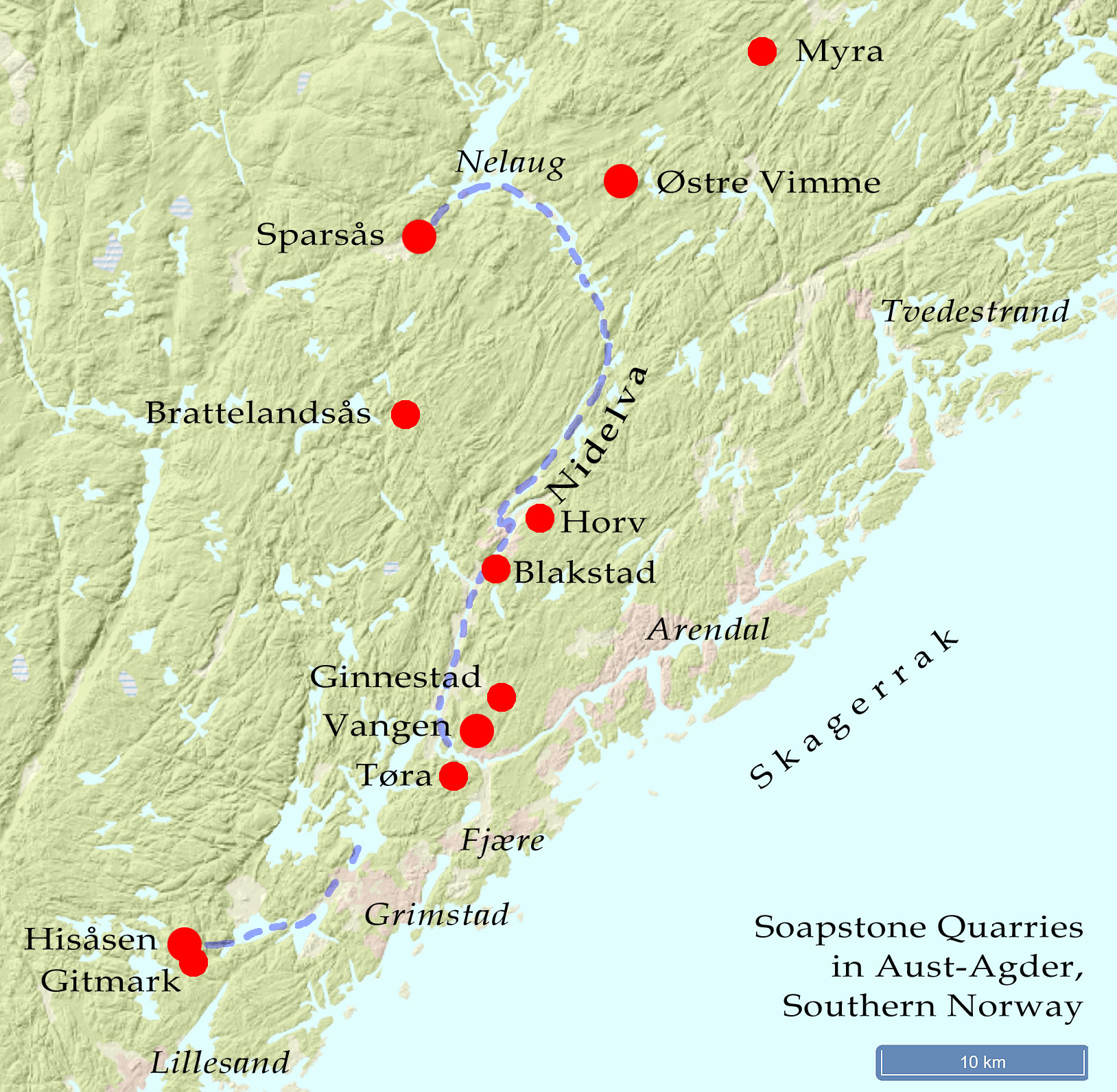

Located by Nelaug in the municipality of Åmli, 20 km from the Skagerrak coast (as the crow flies), Østre Vimme, also called Austre Vimme and Storøygardsås, is only 10 km east of the Sparsås soapstone quarry. The latter quarry was described in a recent article on this website and is entirely different from Østre Vimme. Sparsås is pristine, “orderly” and probably featuring one production phase of “hard” soapstone only, whereas Østre Vimme, with its soft stone, has been affected by both natural and man-made damage, leaving it rather “chaotic” and more difficult to understand.

Overview of soapstone quarries in Aust-Agder, with main transportation routes indicated. Map based on Kulturminnesøk and NGU’s mineral resource database.

Archaeological research history

The archaeological research history of Østre Vimme is also different from the Sparsås quarry. Neither Helge Gjessing (1923) nor Arne Skjølsvold in his 1961 work mention the quarry. However, after finds by locals, in particular a small iron celt (“chisel”), Skjølsvold went to the quarry around 1970 and included the site in an article on tools found in old soapstone quarries (1979). The quarry is also briefly described in a book on the history of Agder (Låg 1999) and mentioned in several later works on the significance of the regional soapstone industry, in particular by Schou (2007, 2017), and see also Holberg & Dørum (2018).

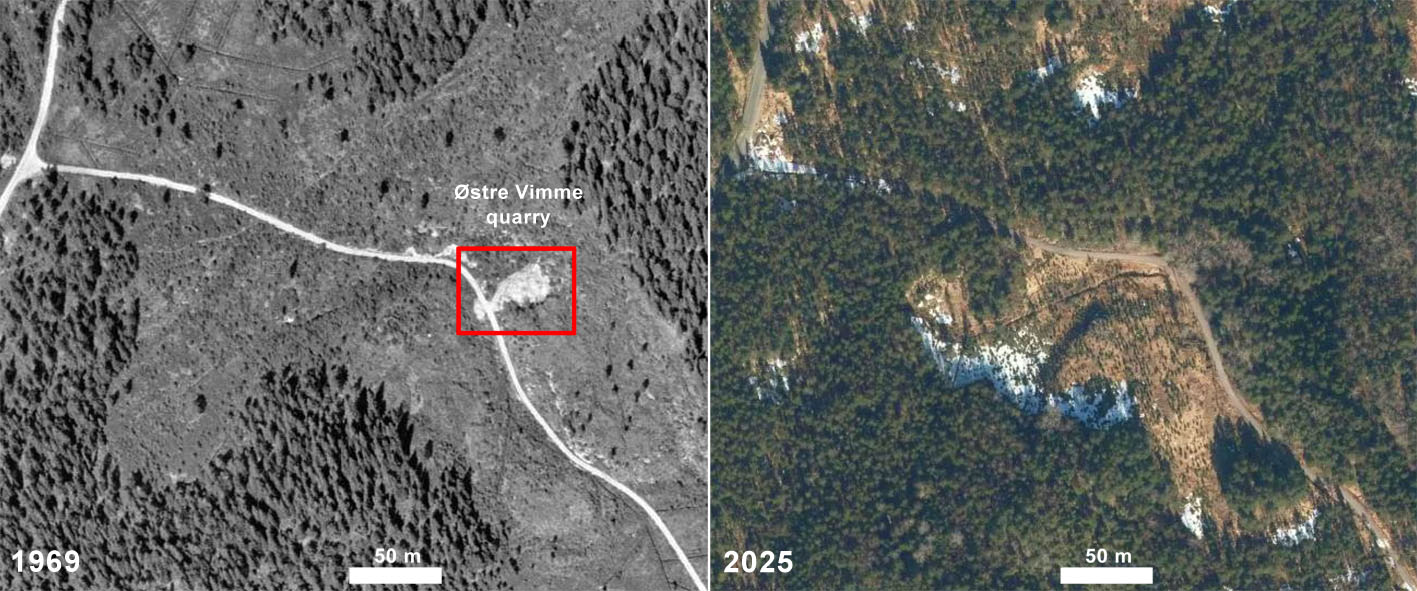

Skjølsvold’s visit took place after the large spoil heap of the quarry had been dug for obtaining material for building a dirt road through the forest in the late 1960s. About 100 lorry loads of soapstone waste were removed from the heap, implying that it was possible to get an idea of the stratigraphy of the spoil. Three distinct layers with dark “stripes” in between were observed, the stripes probably representing turf formed in periods of less intensive exploitation (Skjølsvold 1979).

The spoil heap of the Sparsås quarry was used for road building in the late 1960s. Here are aerial photos of the situation in 1969 and 2025. Source: norgeibilder.no

The Sparsås quarry after digging the spoil heap for road material in the late 1960s. Note the steep cliff, which was undermined by quarrying, leading to detachment of all the blocks covering the western part. Photo by Arne Skjølsvold, in Skjølsvold (1979).

Many discarded soapstone objects were recovered, among them vessels with a form typical of the Viking Age (R729), but also several other smaller and larger half-finished and broken vessels. In addition, half-finished/broken sinkers or loom weights, as well as fragments of circular discs were found. However, the finest object was an iron celt, presumably to be hafted as a pick, discovered in the uppermost/youngest layer of spoil. Skjøsvold (1979) discusses the celt at length, comparing it to other, similar finds in Norway. He infers that it has a form typical of the Viking Age and the preceding Merovingian period.

Fiane & Aabakk (2009) in their historical description of the Østre Vimme farm, to which the quarry belongs, extend Skjøsvold’s account by the interesting remark that nearby moors have names relating to soapstone production (Blautgråssmyra, Blautgråsskjerret). Since in Norway there are several finds of soapstone vessels deposited in moors (Skjølsvold 1961), perhaps there is something to be found also in the Østre Vimme moors?

Selection of objects found in the Østre Vimme spoil heap. Note the light colour of the soft soapstone and the rust-coloured spots. Photos by Kulturhistorisk Museum, UiO, in digitaltmuseum.no, where detailed descriptions can be found.

The iron celt found in the spoil heap in the late 1960s. Photo by Universitetets Oldsakssamling, from Skjølsvold (1979)

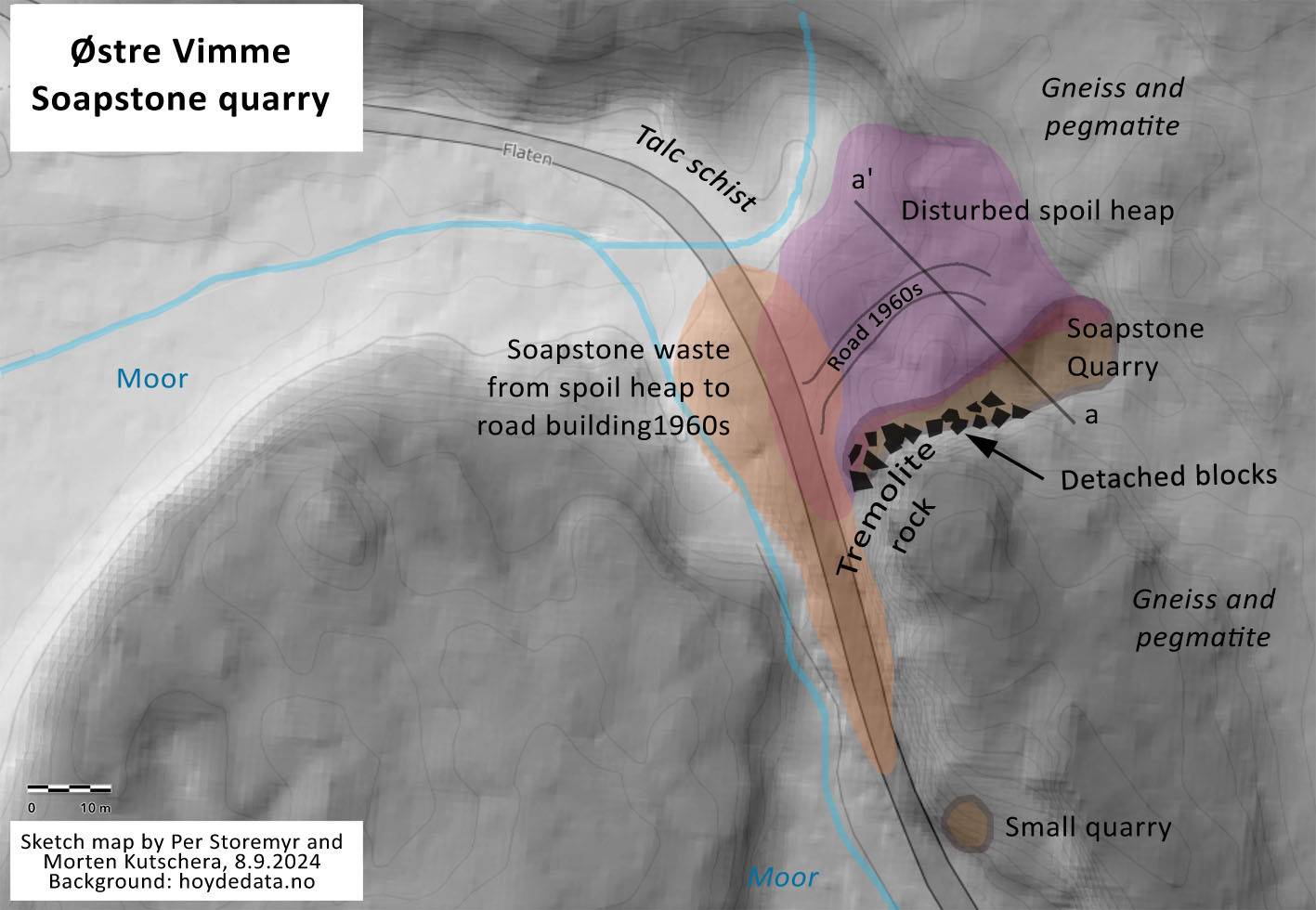

Quarry layout and spoil volume

Though important finds were recovered, the quarry was heavily damaged by the digging in the 1960s, which must have removed an estimated 200 m3 from the spoil heaps. However, natural damage probably started well before the modern era. Since the quarry is located on the north side of a 40 m long hillside, and because quarrying undermined a c. 6 m high cliff, much of the western part of the quarry has been buried by rock fall. According to Skjølsvold (1979), the horizontal depth of the underground operations must have been about 4 m. In the eastern part, where the hillside is just slightly undermined and a few vessel extraction marks are still visible, a small pond with uncertain depth has developed within the quarry.

Sketch map of the quarry and its near surroundings, by PS and Morten Kutschera 2024

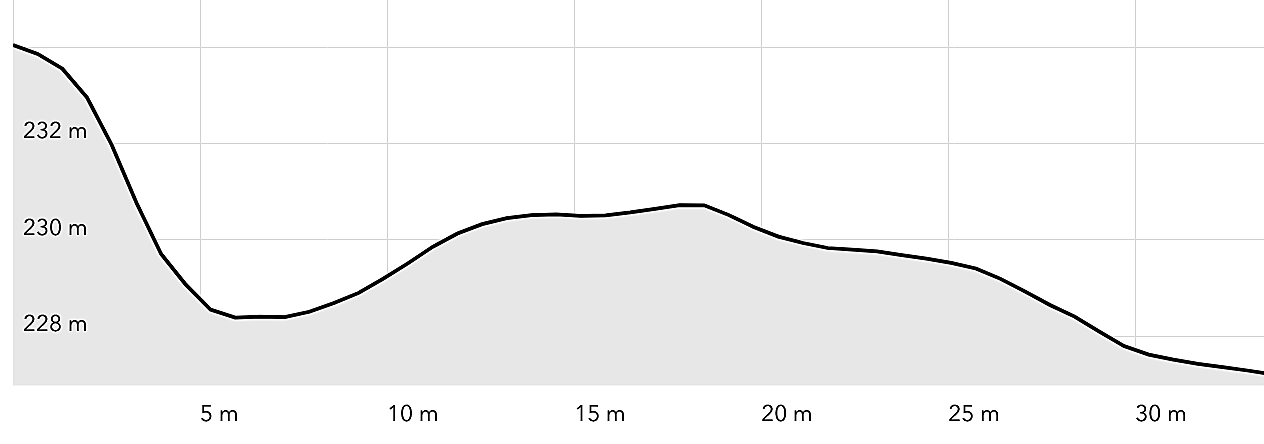

Elevation profile a-a’ in map above. From hoydedata.no

Due to the rock fall, it is not easy to get an overview of the quarry’s western part. However, since the detached blocks are big, it is possible to sneak in between them. There are some vessel extractions marks on the blocks, but most interesting is that the blocks have preserved a rather pristine quarry floor. We had too little light to study the moist floor in detail during our visit, but it is dotted with smaller and some larger remains of degrading, soft soapstone fragments from the quarrymen’s work. It may well be that the small “caves” hide interesting clues about the operations.

From measurements using Lidar-maps, the spoil heap has an area of about 800m2. Skjølsvold (1979) notes that its height was up to 8 m before the digging in the 1960s. This probably is an exaggeration. From several Lidar-map profiles, a present maximum height of about 4 m can be inferred, and the average is probably less than 2 m. In sum, then, including an estimated 200 m3 used for road building, a spoil volume of some 1500 m3 would seem reasonable.

Using the same calculation method as for the Sparsås quarry, a total number of “standard” Viking Age vessels produced may have been in the order of 3-4000. But given that also other types of items were manufactured, this figure must be considered an extremely rough estimate of the quarry output.

The Østre Vimme quarry as seen from the pond in the eastern part. Photo by PS

Mark of vessel extraction on the quarry face by the pond in the eastern part. Photo by PS

The quarry floor below the big blocks that at some time detached from the undermined quarry face. Photo by PS

Geology

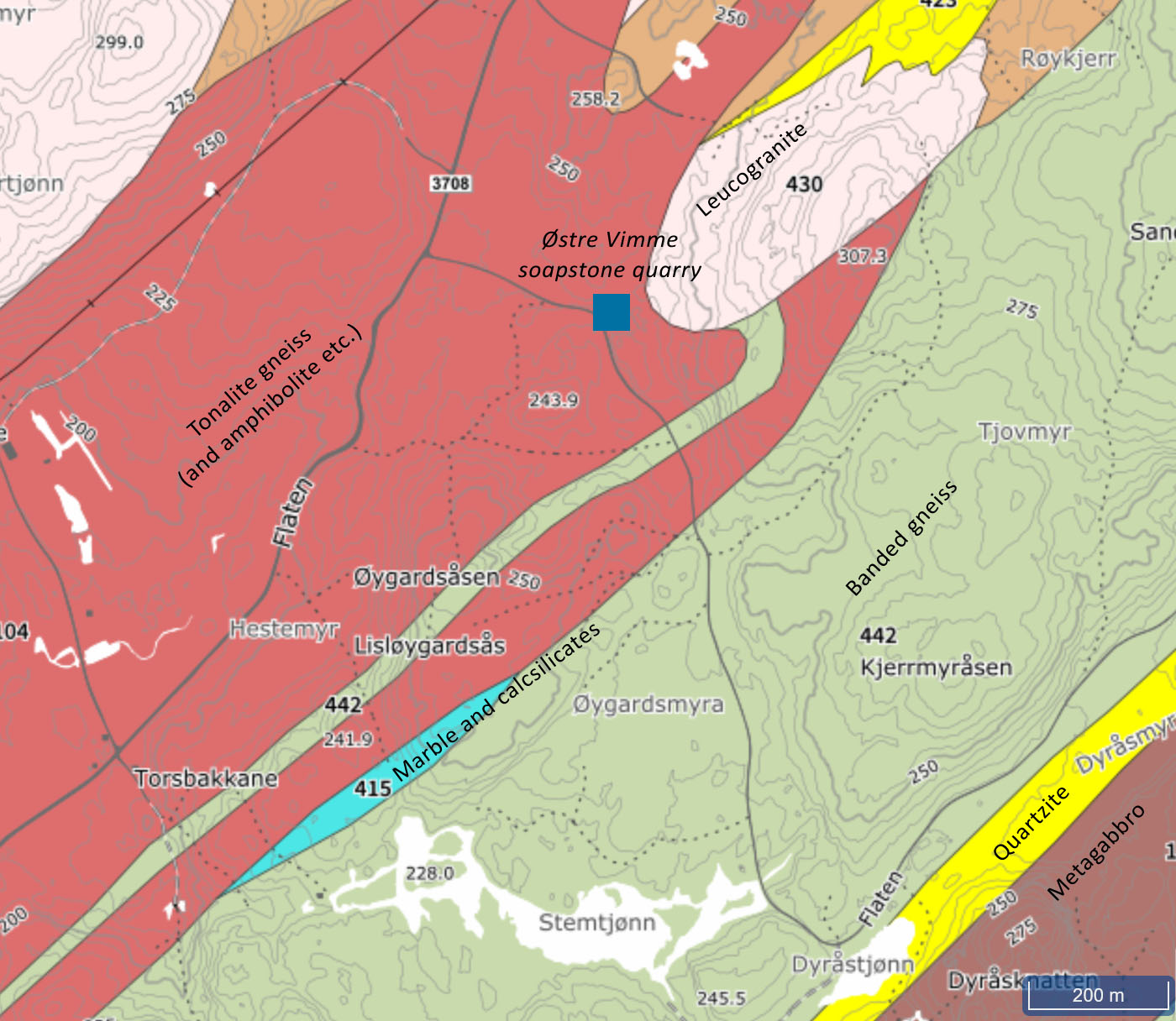

The Precambrian geology in the area of Østre Vimme is rather similar to the Sparsås quarry, with various metasedimentary gneisses, amphibolite and quartzite (review in Nijland et al. 2014). However, there are calcsilicate rocks and marble close to the quarry, indicating skarn formation, for which the Aust-Agder/Arendal region is well known (cf. skarn iron ore deposits). No ultramafic lenses have been reported close to the quarry, but further away there are quite large bodies of metagabbro (see the geological map below).

The gneisses around the quarry are migmatitic, quartz-rich, criss-crossed by pegmatites, and just to the east is a body of unfoliated leucogranite (cf. Moree & Nijland 1996, Moree 1998). In a zone 0,5-1 km to the northeast, small iron ore deposits have been reported and there are also minor nickel-deposits quite close, both as of yet unclear origin (Fiane & Aabakk 2009, see also the Mineral resources database by the Geological Survey).

Simplified geological map from the Geological Survey of Norway. Rock unit characterization partly from Moree & Nijland (1996)

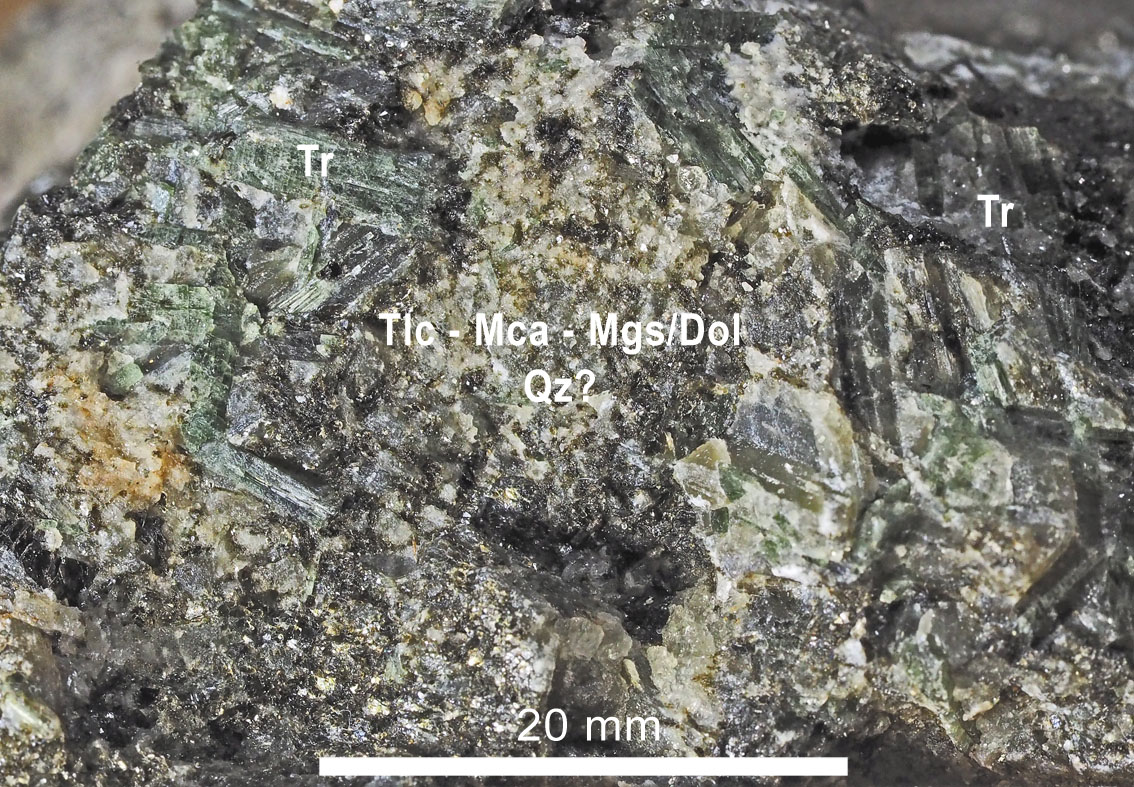

In zones within and just beside the quarry is a coarse-grained, almost pegmatitic, tremolite-rich rock, sometimes showing asbestiform tremolite. Preliminary assessment by visual inspection, including stereo microscopy, and tests with cold and hot 10% HCl, shows that this rock also contains variable amounts of mica (biotite/phlogopite), talc, as well as a little magnesite (or dolomite) and quartz.

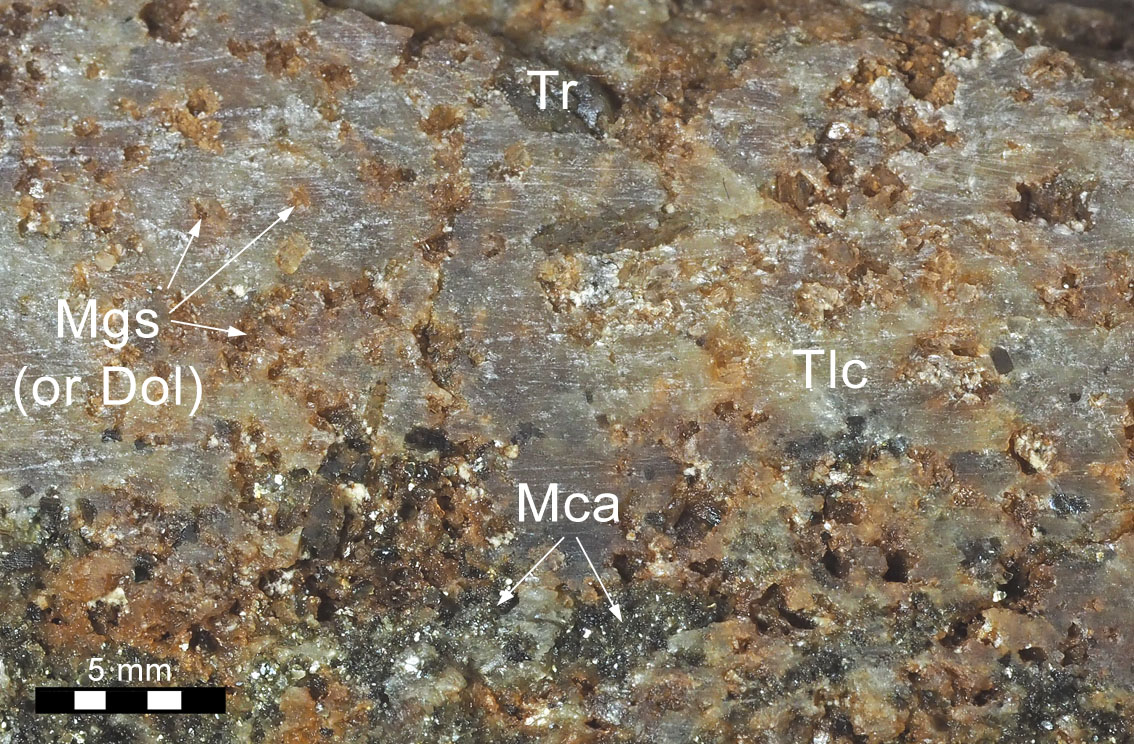

Interestingly, the rock grades into the light, soft and very talc-rich soapstone, which was the main target of prehistoric exploitation. In addition to talc, the soapstone contains some tremolite, magnesite (or dolomite) and mica (biotite/phlogopite). In the eastern part of the quarry the rock is rather schistose and north of the spoil heap is also a zone of schistose, talc-rich rock. Along the dirt road, about 50 m south of the main quarry indistinct tool marks define a smaller extraction spot.

Previous visitors have also noticed the light, soft and talc-rich character of the Østre Vimme soapstone (Skjølsvold 1979, Frigstad 2004). Frigstad (2004) thus maintains that it is different from other soapstone deposits in Aust-Agder. No doubt this is an important reason why the quarry features multiple use periods and several types of manufactured items. The stone was simply very easy to carve.

But it is hard to observe the softest varieties in solid rock today, neither in the open, eastern part of the quarry, nor below the rock fall in the western part. But on the quarry floor below the rock fall, as well as in the spoil heap, soft fragments are omnipresent.

Talc-tremolite rock in the Østre Vimme quarry. TR=tremolite, Tlc = talc, Mca = mica, Mgs/Dol= magnesite/dolomite, Qz=quartz. Photo by PS

Soapstone in the Østre Vimme quarry. Tlc = talc, Mca = mica, Mgs/Dol= magnesite/dolomite, Tr=tremolite. Note the brown rust colour associated with the carbonates. Photo by PS

Fragment of an unfinished vessel carved in a less pure variety of soapstone from Østre Vimme. The dark minerals are mica and some tremolite. Compare with objects carved from much purer soapstone in photos above. Photo by Kulturhistorisk Museum, UiO, in digitaltmuseum.no

Formation of the soapstone

Importantly, Dutch geologists, on studying the geology of the Bamble Sector of the South Norwegian Precambrian, have analysed and interpreted the unusual tremolite-talc-phlogopite rocks, including the most talc-rich varieties (Moree & Nijland 1996, Moree 1998). Although a certain content of magnesite (or dolomite) is not mentioned, the analyses roughly correspond with my assessments, showing tremolite (up to 90%), talc (up to 90%), quartz (0-50%) and phlogopite (10-40%), with rutile, zircon, apatite and tourmaline as accessory minerals.

Moree and Nijland maintain that the rock is extremely rich in both Mg and Si, which would exclude that it is derived from an ultramafic precursor, the most common mode of soapstone formation in Norway (Storemyr & Heldal 2002, Hansen & Storemyr 2017). Rather, given the metasedimentary geological environment, they prefer a sort of skarn formation or metasomatic alteration of siliceous dolomite prior to regional metamorphism. Moreover, they infer that the heat needed for alteration may have been provided by intrusion of the unfoliated leucogranite just to the east of the soapstone quarry.

Comparison with the Nordland talc deposit

I can hardly judge the validity of the intriguing interpretation, but if correct, the Østre Vimme deposit is special, indeed, as there is currently only one other known soapstone deposit in Norway derived from dolomite. This is the Nordland (or Stølsfjellet) deposit in Høle, east of Sandnes in Rogaland. Already in 1945 geologist Odd Mortensen made a detailed study of the deposit and convincingly suggested that it was formed by metasomatic alteration of dolomite, with heat and silica-rich solutions provided by intrusion of a very quartz-rich rock.

The usable Nordland soapstone occurs in zones within an altered rock ranging from almost pure talc to calcium-rich marble with serpentine (ophicalcite). Apart from talc, serpentine and carbonates (calcite, dolomite, magnesite), other minerals present include tremolite, epidote and chlorite (pennine), as well as traces of pyrite and sphene (Mortensen 1945).

Minor amounts of both soapstone and marble have been extracted from the deposit in early modern to modern times, and it also has a history as a talc mine. Marble with serpentine was, for example, used for the façade of the so-called Serpentingården in Oslo (1898) (Reusch 1913, Bugge 1929, Bergsåker 1964, see also mindat.org and the Mineral resource database). Archaeological investigations have, to my knowledge, not been undertaken; hence it is unclear whether the quarry has a history back to the Middle Ages or earlier, for example for vessel production.

The Nordland soapstone (or the talc-rich variety, steatite) is greyish white and clearly different from the Østre Vimme soapstone. From a purely visual perspective, magnesite (or dolomite) from Østre Vimme tends to become slightly rust coloured upon weathering, probably due to a certain content of iron. This has not been observed in the Nordland soapstone.

Impressions from the Nordland quarry. Clockwise from top left: 1. Spoil heaps from talc production. 2. Spot with very talc rich rock. Note the greyish white stone (here with some organic growth) and absence of rust-coloured spots. 3. Calcitic marble with serpentine. 4. Layered talc-rich rocks. Photos by PS (1998). See also Storemyr (2000)

Geochemical provenance studies

In the recent work of Skowronek & Chmielowski (2024), both the Østre Vimme and Nordland quarries are mentioned as possible places of origin for a group of very talc-rich, Iron Age soapstone vessels found in Ribe (Denmark). Their “Group II” vessels, dating to the first half of the 9th century CE, have high MgO and SiO2 values, moderate Fe2O3 values and very low values of Co, Ni and V (see online publication for details).

Much of the Ribe data are in quite good agreement with the whole rock chemical analyses from the Østre Vimme quarry samples TN3 and TN4, provided by Moree (1998) (SiO2 56-58%, MgO 22-26%, Fe2O3 4-5%, V 21-26 ppm, Co 12 ppm, Ni 65-69 ppm). However, the Ribe vessels are practically devoid of CaO, which contrasts with the Østre Vimme data (6-13%). A CaO analysis from the Nordland quarry is also available and at more than 30% (Mortensen 1945) it deviates much from the Ribe analyses.

The implication of these deviations is unclear, but as for Østre Vimme, it is not entirely unlikely that it is connected to sampling strategy. Recalling that Moree & Nijland (1996) and Moree (1998) analysed samples without carbonates, whereas in my assessments magnesite or dolomite are clearly present, there will be significant variations within the quarry, also, for example, as regards the Ca-bearing tremolite, which may not be present in the softest/”purest” soapstone varieties.

Outlook

As for Østre Vimme the geochemical data deserve further consideration; ideally with reassessment from new sampling campaigns and analyses, including petrography. In addition, a more thorough geological investigation would be desirable to substantiate whether the deposit really is derived from dolomite.

For future provenance studies, it may be that initial screening of vessels from archaeological excavations may take advantage of the fact that the Østre Vimme soapstone is very soft and talc-rich, usually with rust-coloured spots associated with carbonate and sometimes with visible clusters of small, dark grains of mica. Moreover, from current knowledge, visually it is quite different from the greyish white Nordland soapstone.

Østre Vimme is a damaged and chaotic old quarry, now hidden in the forest. Behind this veil is an incredibly exciting quarry worked by generations of craftspeople. Maybe one day proper archaeological excavation and geological survey can reveal more details of their fine work.

Many thanks to archaeologist and stone artisan Morten Kutschera of the Agder County Council, with whom I visited the quarry in September 2024.

References

Bergsåker, J. 1964. Høle gjennom hundreåra. Sandnes

Bugge, A. 1929. Beretning om arbeidet i 5-årsperioden 1924-28. NGU, 133, 11-19

Fiane, E. & Aabakk, H. 2009. Åmli. Ætt og heim. Bind III: Vimsbygd. Åmli kommune

Frigstad, O. F. 2004. Kleberstein – en utstilling i Åmli. Agder naturmuseum og botaniske hage. Årbok 176, 28–33

Gjessing, H. 1923. Aust-Agder i forhistorisk tid. In Scheel, F. (ed.) Arendal fra fortid til nutid: utgit ved byens 200-aars jubileum som kjøbstad 7. mai 1923. Kristiania, 1-56

Hansen, G. & Storemyr, P. (eds.) 2017. Soapstone in the North: Quarries, Products and People. 7000 BC – AD 1700. UBAS University of Bergen Archaeological Series, 9

Holberg, E. & Dørum, K. 2018. Arendal før kjøpstaden. Fram til 1723. Arendal by- og regionshistorie, bd. 1, Oslo

Låg, T. 1999. Agders historie. 800-1350. Agder historielag, Kristiansand

Moree, M. 1998. The Behaviour of retrograde fluids in high-Pressure settings. Implications for the petrology and geochemistry of subduction-related metabasic rocks from Catalina Island (California, USA) and Syros (Greece). PhD Thesis, Free University Amsterdam

Moree, M. & Nijland, T. G. 1996. The Vimme talc deposit: field occurrence, whole rock chemistry & Pb isotopes. In SNF excursion Numedal-Telemark-Bamble, 22-25 aug. 1996. Unpublished report

Mortensen, O. 1945. Vannholdige magnesiasilikater dannet ved metasomatose av dolomitiske kalkstener. Norsk geologisk tidsskrift, 25, 266-284

Nijland, T. G., Harlov, D. E. & Andersen, T. 2014. The Bamble Sector, South Norway: A review. Geoscience Frontiers, 5, 5, 635-658

Reusch, H. 1913. Tekst til geologisk oversigtskart over Søndhordland og Ryfylke, NGU, 64

Schou, T. P. 2007. Handel, produksjon og kommunikasjon – en undersøkelse av klebersteinsvirksomheten i Aust-Agders vikingtid med fokus på Fjære og Landvik. Master thesis, University of Bergen

Schou, T. P. 2017. Trade and Hierarchy: The Viking Age Soapstone Vessel Production and Trade of Agder. Soapstone in the North: Quarries, Products and People. 7000 BC – AD 1700. In Hansen, G & Storemyr, P. (eds.), UBAS University of Bergen Archaeological Series, 9, 133-152

Skjølsvold, A. 1961. Klebersteinsindustrien i vikingetiden. Oslo

Skjølsvold, A. 1979. Redskaper fra forhistorisk klebersteinsindustri. Universitetets Oldsaksamling 150 år. Jubileumsårbok, s. 165-172

Skowronek, T. & Chmielowski, R. 2024. Geochemical constraints on the provenance of Viking Age soapstone finds from Ribe, Denmark. By, marsk og geest, 36, 4-21

Storemyr, P. 2000. Stein på Stavangerkoret/Undersøkte steinbrudd i Rogaland. I Storemyr (red.) 2000. Restaurering av Stavangerkoret 1997-1999. Dokumentasjon av arbeidene, NDR-rapport nr. 2/2000. Published as CD-ROM (zip-file, 260 MB)

Storemyr, P. & Heldal, T. 2002. Soapstone Production through Norwegian History: Geology, Properties, Quarrying and Use. In: Herrmann, J., Herz, N. & Newman, R. (eds.): ASMOSIA 5, Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone – Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference of the Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, June 11-15, 1998. London: Archetype Publications, 359-369.

Discover more from Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology & Conservation

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Soapstone in the Far South of Norway (I): The Sparsås Iron Age Quarry | Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology & Conservation