Even until the 1950s the quarrymen in Berne extracted their sandstone using pickaxes. They carved out trenches around the blocks to be removed, not unlike the way their colleagues did 5.000 years ago in ancient Egypt. Why so? Join me on a trip to the Sandsteinlehrpfad in Krauchthal and Wege zu Klee in Ostermundigen to find out – and to learn about Berner Sandstein. It was a most important stone in Switzerland, giving rise to historic quarry centres substantial on a European scale.

Switzerland is a small country, but thanks to its geology it is big in terms of historic stone architecture. Consequently, it has major historic quarry centres, particularly in the Berne region. Though not as large as the giants, such as Vienna, Paris and Caen (and Rome!), Berne is comparable to major medieval and early modern quarry hubs in Central Europe. In this account the two initiatives focusing on this heritage will be presented – the sandstone quarry trail in Krauchthal and the Paul Klee theme path in Ostermundigen. But it will also explain the extraction technique of Bernese sandstone and its antecedents 5.000 years ago. And it ends with the Bernese quarrymen’s affection for schnaps and beer – something they had in common with, yes, their Bronze Age colleagues!

Bernese sandstone

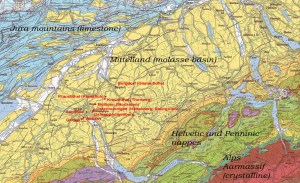

Geologic map of Switzerland with the Bernes sandstone quarries mentioned in the text. (Map 1:500.000, Institut für Geologie, Universität Bern/ Bundesamt für Wasser und Geologie)

View of the city of Bern in 1638. Copperplate engraving by Matthäus Merian. The Sandflue quarry is marked by an arrow, the minster by a circle.

Bernese sandstone occurs as thick and soft, nearly horizontal beds in the so-called Upper Marine Molasse, which was formed by the material that rivers transported from the rising and simultaneously eroding Alps into a shallow ocean about 25 million years ago. There are many historic quarry centres, first of all Berne itself, with old quarries in the city (Sandflue, now built over) and at nearby Wabern and Gurten. Others are located by Ostermundigen and Bolligen (Stockeren). A bit further away from Berne are the Krauchthal quarries to the east, followed by the Burgdorf-Oberburg quarries. In the west, around Fribourg, is another group of quarries in Bernese sandstone. And there are many more.

As they appear today, the preserved quarries generally have a history back to the 18th and 19th century, but there is ample evidence that quarrying commenced already in the Roman period. It intensified greatly in the Middle Ages and since then regular extraction took place, supplying nearby cities, towns and villages. The heyday started in the 18th century and quarrying boomed for a few decades from the mid 19th century, especially because the city of Berne became capital of the new Swiss federation in 1848. This prompted massive building works, for which huge amounts of sandstone was needed.

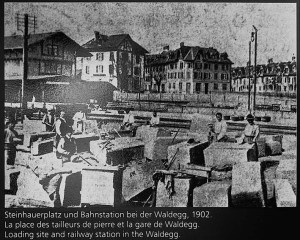

With the advent of the railway in the second part of the 19th century, stone was also exported throughout Switzerland. But as modern building materials took over, the industry declined. Today there are only three active quarries, mainly delivering stone for restoration purposes: Gurten, Krauchthal (Thorberg) and Ostermundigenberg.

The old architecture of the whole region is characterised by the yellowish to greenish to greyish to bluish sandstone, but this is nowhere as distinct as in the old quarters of Berne itself. Though restored and renewed, the houses and streets still transmit their medieval atmosphere, which was a main reason for the city’s inscription on the World Heritage List in 1983.

Though quite homogeneous, Bernese sandstone is not uniform, and for the stone carver there is ample difference between varieties of e.g. “hard” and “soft” stone. The bluish-greenish beds at Gurten by Berne and the so-called “Church bed” (Kirchenbank or Kilchenbank) at Ostermundigen are known for their particularly good and durable stone, mainly because they are fine-grained and relatively compact. These beds were much sought after and the name “Church bed” indicates that it was reserved for one of the most important buildings, the Berne Minster (Berner Münster), built from 1421 onwards.

Looking for the best beds was usually of importance, but during the building booms almost any stone would do, also relatively coarse-grained, less compact material, and this is part of the reason why Bernese sandstone has a pretty poor reputation: Stone from inferior beds easily disintegrates and develops scales, especially under the influence of soluble salts. And this again is a reason why so many buildings have been and are in need of restoration.

The Krauchthal trail

The sandstone trail at Krauchthal is a classical one for experience and learning, in particular designed for the local audience – including kids. It starts at the local museum, featuring information posts on geology and history at important quarries, landmarks, old roads and some buildings. A wonderful, half-day walk in the forested, hilly landscape – following in the footsteps of the 150 quarrymen (Steinbrecher) and stone masons (Steinhauer) who paid their taxes to the municipality in the heydays of the second part of the 19th century.

The first quarry, active until about 1875, is impressive: With a ground plan of just 18 x 33 m, Kreuzfluh towers 51 m high – or sinks 51 m down – depending on the perspective! It is almost a true vertical “hole “, with walls on each side, the lowermost only broken by the high and narrow, cut access road.

Bäichle, the next quarry, is much smaller, a “normal” 19th century quarry cut into part of a gentle hill slope. This is used as a place where visitors can put their names on the quarry wall – a guest book in stone! Also, if you contact the local museum, they will lend you tools for working stone here. Not a bad deal!

Then follow the small Brecherfluh quarries, at the bottom of a picturesque natural cliff. The largest local quarry, at Thorbergstrasse, over the centuries developed to a true underground mine. This quarry is the one still in operation and not part of the sandstone trail, which is also the case with at least ten other, mostly smaller quarries in Krauchthal.

A good place for a break is on the top of Chrüzflueh with its pavilion and grand vistas across Krauchthal. To climb the hill you partly use cut-out stairs in the sandstone, but it may be slippery here and elsewhere along the trail, so you will definitely need good shoes!

Wege zu Klee

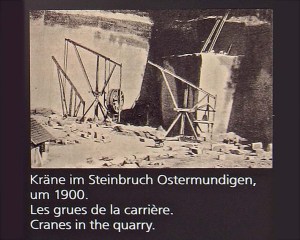

Wege zu Klee (“Roads to Klee”) is the second initiative presenting the rich regional quarrying history to the public, an initiative launched by the municipality and the museum Zentrum Paul Klee, located between Berne and Ostermundigen. The trail, or theme path, follows in the footsteps of the famous Bernese painter Paul Klee (1879–1940), to whom the Ostermundigen quarries were a great inspiration.

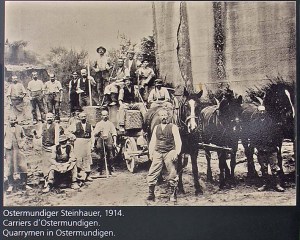

Ostermundigen was the largest regional quarry centre in the second part of the 19th century, even the largest in all of Switzerland, before the boom abruptly came to an end. Up to 500 quarrymen, including many immigrants, were engaged as quarriers and masons and in 1871 the world’s first combined rack railway was constructed to bring the stone easily from the quarries to the railway station.

In addition to the stone mason’s workplace by the railway station and the quarrymen’s houses, the posts at Wege zu Klee concentrate on the part of the quarry that is still in operation at Ostermundigenberg. Here are several of Klee’s paintings exhibited, placed in such a way that one can understand the scenery he saw when he worked. In fact, the famous Bibémus quarries in Aix-en-Provence (France) are presented in a similar way to the public, relying on the paintings by Paul Cézanne, who inspired Klee significantly.

But Ostermundigenberg was only the last quarry to be opened in the 19th century. Earlier, and back to the Middle Ages, extraction took place a bit further east in quarters now known as Hättenberg and Steigrübli. These have to a large extent become covered by houses and new infrastructure, but there is still activity in part of the Steigrübli, now as the scene for the popular theatre group of “Madame Bissegger“. A good way of reusing an old quarry!

Cutting the trenches

Cutting the trenches with pickaxe. Source: Drawing after photo from Franz Gfeller (in Gisiger 1993, p. 17)

With the exception of the still-active quarries, extraction took place with the sole use of manual labour. And this basically meant carving narrow trenches around the blocks to be removed. A special double pickaxe, the Schrotpickel, was the main tool. The quarrymen used it standing beside the trench, typically with one knee on the ground, hacking out the sandstone, whereas the debris in the trench was removed with a tool called Schrothaue.

In this way a remarkably regular pattern of parallel, curved lines on the quarry walls developed – marks that are similar in all Bernese quarries. They are also found in most other Swiss sandstone quarries. With the trenches around the block completed, it could be loosened at the base, i.e. along the bedding plane of the sandstone, using short wedges placed at regular intervals.

This extraction technique was the only one used until the end of the 19th century. But in many cases it was even applied until the 1950s. However, with the advent of pneumatic drills and jackhammers such machines slowly replaced the pickaxes. And from the 1950s onward chainsaws and wire saws soon became the primary means of extracting the blocks.

The reason why manual labour persisted for so long probably has two reasons: One the one hand Bernese sandstone is, when quarry moist, soft enough for this traditional technique to be extremely well adapted. On the other hand the sandstone industry was in massive decline in the first half of the 20th century, implying that quarry companies may not always have had the necessary means to invest in more modern equipment.

*

An extraction technique used for 5.000 years

Cutting regular trenches is definitely not the oldest technique of extracting stone from bedrock, but it is the oldest one for obtaining squared building blocks. Whereas splitting with stone tools and firesetting was used for getting pieces of hard rock to utensils, jewellery, artwork, weapons and ritual objects since time immemorial, the trench method generally commenced with the introduction of stone architecture. And this took place in the Early Bronze Age in the Near East, 4.600-4.700 years ago – in Saqqara in Ancient Egypt, when Pharaoh Djoser and his architect Imhotep decided to refrain from traditional mud brick and build the Step Pyramid in the local, soft limestone.

The difference between cutting trenches with chisel and mallets (straight lines), and pickaxe (curved marks). Small Graeco-Roman quarry at Elkab, Upper Egypt

From then on soft stone, when available, was the preferred material for representative architecture of the elite, enhanced by sculpture and decoration in hard stone. It is a story of the rise of complex societies and cities, and a story intimately connected with metal technology. For soft rock can be cut efficiently with bronze tools. Thus, throughout Ancient Egyptian history limestone, sandstone and travertine was extracted by cutting regular trenches using bronze chisels and mallets. It started with open-pit quarrying, which was soon supplemented with underground extraction in vast galleries along the Nile Valley, most of which have survived until this day.

With the introduction of iron technology in the last millennium BC, the use of chisels and mallets seems to have continued for some time in Egypt, but the Greeks and Romans generally preferred iron pickaxes to cut the trenches – as did the Nabateans in their impressive sandstone quarries in Petra (Jordan). Rome was built by squaring blocks from its vast deposits of soft travertine and volcanic tuff – and the pickaxe was also the main tool for extracting the harder marble. But marble quarrying was occasionally carried out by wedge splitting, the method preferred for extracting hard rock (such as granite) over the last 2000 years – a method sometimes also applied for soft rock.

Many medieval and later cityscapes would have been unthinkable without soft stone extracted by cutting regular trenches with pickaxes; examples especially include world-famous quarries in France, notably the limestone quarries in Paris and Caen.

Steps and platforms

Looking at the remains of ancient open-pit quarries, there is often a striking pattern of irregular steps rising from the quarry floor. This is the result of the most common extraction process in homogeneous soft stone deposits: the stepwise lowering of the quarry front, which usually was initiated along a hill slope or low escarpment. We find very good (and very early!) examples in the large quarries surrounding the pyramids of Giza.

But at Giza we also find the remains of another extraction process; the sinking of a whole platform cut up in huge, regular building blocks – looking like the pattern on a Swiss chocolate slab. This is the famous quarry on the north side of the second – or Chephren’s – pyramid. Apparently, the builders and quarrymen must have regarded this process more efficient than working stepwise – they thus avoided the carving out of difficult corners – and perhaps it was also necessary in order to obtain the very large blocks used in the lower parts of the pyramids.

In many quarries we find variations of these two processes, e.g. in Petra, where stepwise extraction took place along slopes and a peculiar mode of quarrying was applied along very tall, vertical cliffs: The quarrymen made a small cut 30 or 40 metres above the valley floor and then extraction proceeded downward – and slightly inward – to achieve maximum output without compromising security.

Just like in Petra: Quarry at Brecherfluh, Krauchthal. Note that a big block has fallen after quarrying took place (red lines)

A similar method can, in fact, be recognised in the Bernese quarries 2000 years later. At the tall rock face by Brecherfluh in Krauchthal quarrying was undertaken in a nearly identical manner, but there are even better examples along the cliffs in nearby Burgdorf. Today the latter 18th century quarries in Burgdorf are slightly obscured by vegetation, but on old paintings they appear as their Petra counterparts.

Obviously an efficient method of “attacking” a tall cliff without moving to underground quarrying, the “Petra method” was followed by many other ways of laying out the quarries in the Berne region – ways that were dependent on the local topography, what the quarry was intended for and the sizes of the blocks to be extracted. And as the demand for stone rose, the manual craft of extracting stone approached industrial dimensions and efficiency – and hardly anywhere is this as clear as in the 19th century Kreuzfluh quarry in Krauchthal. For in this quarry, which appear as a deep, vertical hole in the hill slope, broad platforms were divided into many large blocks, just like at Giza 4.500 years earlier to avoid working difficult corners, and successively sunk up to 50 metres down!

Illustration of how a whole platform of cut blocks was sunk in the 19th century. From the quarry trail in Krauchthal

As soon as the platform was subdivided each block was loosened at the bottom and then simply tossed over the edge, landing softly on built-up quarry debris (the Stucknest) many metres below. Then the blocks were roughly dressed, loaded on horse carts and brought out along the serpentine-like quarry road to the village and further to the building sites – from the mid-19th century to the nearest railway station.

Sinking platforms with place for as many as 20-30 blocks was an important, general quarrying method in the homogeneous Bernese sandstone, though block sizes would probably have varied with time. We find it in the 19th and 20th century open-pit quarries in Ostermundigen, and it is still used here, as well as in the active quarry at Gurten. The method can also be seen in modern quarries elsewhere in the world, for example where homogeneous granite is extracted to large depths. But in other modern Swiss sandstone quarries the more normal stepwise extraction is also applied. Of course, in the active quarries machines are used for cutting the blocks – and tossing them over the edge has been replaced by lifting them out with big cranes.

Hard work – early death

It is remarkable that an essentially Bronze Age technique easily survived the Industrial Revolution up to quite recently. Though many would see this as a confirmation that the stone craft never was particularly innovative, one could also argue that cutting soft stone with pickaxes remained exceptionally well adapted to the task: to make square blocks.

Similarly, many would insist that cutting stone with a pickaxe is extremely hard work, suited for punishing slaves and prisoners rather than constituting the normal daily activity of highly experienced craftsmen. Yes, as many kinds of manual labour, extracting stone was hard work, quite often followed by accidents, illness and early death – and poverty when little or no work was available. This definitely also applied in the Berne region.

Generally, in medieval and post-medieval Europe, quarrymen were mostly poor, the sons following in the footsteps of their fathers, with large families to care for, and mostly at the lower levels of the craftsman hierarchy. Or they were day labourers, though usually highly knowledgeable ones. They often worked for a master, for example a stone mason, owning or renting a quarry; typically a family business going from father to son over decades or even centuries. Or they worked for a master supervising quarries owned by a city, an elite building contractor or an association involved with large building projects (e.g. cathedrals).

But the social status of the quarrymen varied immensely, not only in the Berne region, but also throughout Europe. Essentially, the status depended on how far the stone was treated before it went out of the quarry. If the quarry was also a workshop where extraction and dressing/carving went hand in hand, both kinds of work might be carried out by the same craftsmen, and thus these would have had a status similar to stone masons, legally or in practice. Consequently, in some areas stone quarries were to some extent “schools” – places for recruiting stone carvers. This may apply globally, throughout history. It would be interesting to find out whether it also was a practice in the Bernese quarries.

Schnaps and beer

It is unclear to what extent the quarrymen in the Berne region were organised from the Middle Ages on. But it is very interesting to note that as the stone masons’ fraternity was established in the city of Berne in 1321, masters and journeymen of all stone trades, also quarriers, were accepted. This fraternity developed over Berne’s powerful period as a large city-state to the still-existing “Guild of the Ape” (Zunftgesellschaft zum Affen), “ape” referring to the ability of artists to imitate the wonders of God, but also quite specifically to the quarried, but unworked block of stone.

Also 4.500 years ago: Beer jar excavated from Chephren’s Quarry (Egypt). The archaeologist also seems to have been thirsty…

However, in 1701 the quarrymen were expelled from the guild because of their heavy drinking! Quite an accomplishment, remembering that those who may have assisted the exclusion, the masons and carvers, never have been famous for their abstinence. In the regulations of the Bernese stone masons’ union from 1892, we get a glimpse of the importance of beer at the work places, paragraph 6 firmly stating that it is strictly forbidden to wash the hands in the basins reserved for beer glasses. And in the 19th century heydays the Ostermundigen quarrymen became legendary for their schnaps consumption.

The history of alcohol in quarries seems to go all the way back to the very beginning of large-scale extraction in Ancient Egypt. Though beer was also food in Ancient Egypt, all the beer jars found in the quarries has led some to speculate whether it was used as a way of recruiting the quarrymen.

Alcohol is, of course, not unknown in other parts of society either – especially when groups of men are brought together to carry out hard work. Though it has many facets, one being strengthening of comradeship, the consequences of alcohol in quarries was and is certainly not only fun. But this is another story, perhaps to be written later on.

Links

- Sandstone trail at Krauchthal (Sandsteinlehrpfad)

- Museum Krauchthal

- Wege zu Klee

- Zentrum Paul Klee

- Zunftgesellschaft zum Affen

- Theatre Madame Bissegger

- Bibémus quarries, see also Quarry landscape

of the month at QuarryScapes - For Ancient Egyptian Quarries: See this blog post: Ancient Egyptian quarries: A literature update 2007-2010

- For similar methods in soapstone quarries: See this blog post: Experimental archaeology: The traditional way of quarrying soapstone

- Geologische Karte der Schweiz 1:500 000, 2005. Institut für Geologie, Universität Bern, und Bundesamt für Wasser und Geologi

Literature

- Bezzola, H. (1960): Sandstein – Berner Stein. Der Hochwächter. Blätter für heimatliche Art und Kunst. 16, 352-360.

- Bläuer, C. (1987): Verwitterung der Berner Sandsteine. Unpubl. Dissertation Universität Bern. PDF

- Gerber, M. E. (1982): Geologie des Berner Sandsteins (Das Budigalien zwischen Sense und Langete, Kanton Bern). Dissertation, Uni Bern, 121 p. (Publ. Geolog. Institut Universität Bern, 290)

- Gfeller, F. (1986): Berner Sandstein. Brochure

- Gisiger, U. (1993): Die Berner Zunftgesellschaft zum Affen, Bern, 143 p.

- Hofer, P. (1960): Die vier Sandsteingrubens Berns. Der Hochwächter. Blätter für heimatliche Art und Kunst. 16, 332-351

- Hofer, P. (1970): Fundplätze – Bauplätze. Aufsätze zu Archäologie, Architektur und Städtebau. Schriftenreihe gta, 9, 222 p. (Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag)

- Museum Krauchthal (2006): Sandsteinlehrpfad Kraucthal, Brochure, Krauchthal, 16 p.

- Museum Krauchthal (undated): Information posters along the Sandsteinlehrpfad, Krauchthal

- de Quervain, F. (1963-64): Gesteinskunde und Kunstdenkmäler. Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte, 23, 22-30 + illustrations. PDF

- de Quervain, F. (1969): Die nutzbaren Gesteine der Schweiz, Bern, 312 p. (see p. 213-216)

- de Quervain, F. (1970): Der Stein in der Baugeschichte Berns. Beiträge zur Geologie der Schweiz. Kleinere Mitteilungen, 49 (auch in: Mitteilungen der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft Bern, 27, 9-26)

- Schmalz, K. L. (1983): Ostermundigen. Geschichte. Gemeindeentwicklung. Alte Ansichten. Ostermundigen: Einwohnergemeinde Ostermundigen, 112 p.

- Schweingruber, M. et al. (1971): Heimatbuch Krauchthal, Gemeinde Krauchthal et al., 482 p. (Verlag Haller und Jenzer)

- Soom, Y. (2009): Die Sandsteinbrüche in Burgdorf. Das Burgdorfer Jahrbuch, 76, 95-114. PDF

- Trachsel, H. (ed.) (2006): Sandstein. Eine überraschende Vielfalt. Bern, 120 p.

The sandstone quarries on the map

Pingback: Tusen år med brytning av kleberstein tok nettopp slutt. En historie om mekanisering og globalisering. Og om å gjenoppdage gammelt håndverk | Per Storemyr Archaeology & Conservation

Dear Per Storemyr,

we have a critical key question to your dating the method of sandstone-extraction by pickaxes. Are you realy sure that it was used til modern times esp. 1950? Why should they do this because motor saws are in use since the 20th of the 20century and wedges min. since the Roman times?You know Klemm´s work about Egypt quarries. He distinguishes Old Kingdom til Ptolemaic quarries from medieval and modern by the method of using pickaxes resp. chissels and later on wedges resp. drillholes. Wedges were used not only from Ptolemaic but Kingdom times on and they came in use esp. in the Medieval, because the hard work of hacking tranches were replaced by comfortably drilling or hacking far smaller holes for taking the wedges.

Chronology is that kind of sciense most failures are done.

As you say remarkably regular pattern of parallel, curved lines on the quarrywalls are called to be evidence of the so called tranch-method. But there is a very strange aspect that most researchers neglect. If one hacks a tranch with the pickax he is not able to cut more than 2 or 3 cm deep into the rock. Herakles should have managed several cmtrs. more. In fact man cannot produce marks that are longer than this stretch. But what everyone can see on Switzerland or Egyptian quarrywalls are marks which are til one mtr. long or more. Prof. Stellrecht geogolist from the University of Karlsruhe/Germany was confrontated with such long marks on the quarrywalls of the Zwerchhälde in Sternenfels (www.megalith-pyramiden.de), which hosts an enormous cairn of more than 20 mtrs. height. Dr. Behrends, archeologist of the State Office, supposed it could be a Roman quarry. Stellrecht said that this marks had brought on up front and not through a tranch. This is quite logic because if you hack blind into a tranch you are not able to control the direction and the distance of your impactions except you lead your chissel directly downward. So everyone wonders why? Why should they take effort to smooth the quarrywalls using chissels and pickaxes by curved lines because this work was totally unnecessary? This work was hard and dangerous and it is not imaginable that the owner of the quarry payed for this useless action. In the Kreuzfluh quarry you see close standing rockwalls of 50 mtrs. height. It looks like a rock-cathedral and the patterns seem to be artfull decoration.

We cannot believe that this Switzerland quarrywalls should be formed in modern times. In Burgdorf the Gisnauflüe are showing the same patterns. You see galleries like in Egyptian quarries. My co-researcher Maurice Gernhälder asked a 90 year old woman if she knows anything about quarrywork in her memory. She said not even her parents knew anything about it. On an old picture of 1733 (J. Riediger) the four quarries had the same extention as nowadays. Big missunderstandings, maybe the use of schnaps and beer, must have produced such datings in modern times. Reusing old quarries was and is a common thing. After some time uninterested quarryworkers are not able to differentiate new from old processing tracks. But these laymen are our only witnesses.

In reality Switzerland is full of Celto-Roman quarries which looks like to be transformed into funeral monuments and whole necropolices like Gebel el-Silsila at the river Nile and others Klemm have found. Beyond the prison of Thorberg on the eponymous mountain there is a quarrywall formed like a vast portal and exactly in the middle you can enter a chamber in the rock with domed ceiling which is so small that an origin by stone-quarrying is unpossible. On the south-side of the hill there is another entry and beside a bench cut into the rock. Such rock-benches are part of archeological sites throughout the old civilizations.

With best regards

K. Walter Haug, Walzbachtal/Germany

Dear Mr Haug,

thanks for your lengthy comment. Yes, I’m pretty certain of my interpretations. I think you will find anwers and further information about your questions in a paper I recently wrote together wil James Harrell: “Limestone and sandstone quarrying in Ancient Egypt: tools, methods and analogues”. Abstract of the paper can be found here: https://www.academia.edu/12483606/Limestone_and_sandstone_quarrying_in_Ancient_Egypt_tools_methods_and_analogues_co-authored_with_James_Harrell_. Please send me an e-mail if you are interested in the full paper.

Kind regards,

Per

I am very interested in any kind of information of this object. And we should start a serious scientific conversation about the Schrotgraben-method in medieval and modern times. What we see in Switzerland-quarries cannot be produced during hacking a trench. I am concerned with this problem since 1990 (www.megalith-pramiden.de) as I found the first cairn in such a prehistoric quarry here in South-West-Germany. We are confronted with quarry-walls which are perfekt even – vertical and horizontal – over a stretch of 40 mtrs. or more (Heilbronn, Wallerfangen, Kürnbach, Oberderdingen…) and which are oriented precisly North to South or North-East to South-West. Not the slightest deviation. Never seen before.

Hello again, I see the “Schrotgraben”-method as a very efficient method in soft stones (not so in hard stones, but this is a long story, which involved fire as well as wedges over the centuries). And I totally disagree with you as concerns the Switzerland quarries. Using pickaxes to make trenches is beautifully documented in text and photos until the 1950s. Please read historical documentation (and the paper I suggested for you, as well as many posts on my website), look at historical pictures, before you make inferences as to quarrying methods. Do serious research, let dedicated quarry researchers look at your sites. This is not mystery, this has nothing to do with NE/SW-orientation, but with rock properties and available quarrying methods. Regards, Per

We must distinguish modern quarries from ancient. The Kreuzfluh is surely very old and only compareable to Egyptian and Gallo-Roman. Like you say: “…there is ample evidence that quarrying commenced already in the Roman period”. If you read about the modern trench-hacking-method f. e. Peter Wegmüller “Felsen Höhlen Steinbrüche” the trenches were only cut into a certain deep to take the wedges in. But the technically crash-work was done only by the wedges (p. 110). Therefore the “Schrämmspuren” cannot appear over more the distance the pick-axes carved in, maybe 15 cm or more. But deeper the surface of the rock cannot show this chissel-marks. The cracking wedge produces a complete smooth surface. Therefore parts of chissel or pickax work has to alternate with smooth parts. But what we see in this questionable quarries are rock-walls completely covered by chissel-marks, in the Kreuzfluh 51 mtrs. high. So the quarrymen did a hard job which was completely unnecessary. From an economic point of view this is not understandable anyway.

In Egypt a comparable quarry is Gebel El-Silsila. A temple for the dead and a sphinx make quite sure that this was a necropolis. Tunnels and shafts were cut into the rock to incorporate the dead bodies. Between the carved rockwalls a lot of never explored cairns – missunderstood as normal rubble heaps like we have in Germany. But ours posses megalithic passage graves which everyone can enter.

If you don´t believe you are invited cordially.

Dear Mr. Haug, thanks for your lengthy additional commnets. As you will understand, I totally disagree with you on your interpretation of ancient quarrying.. Could you please provide your e-mail address, and I may send you papers dealing with the “Schrotgraben”-method, which has been in use worldwide in soft stone deposits until quite recently (in Bern until ca. the 1950s, thus there is very good documentation, also photos). Regards, Per

Pingback: The old quarry that was reused as a beer brewery | Per Storemyr Archaeology & Conservation

Hi Paul, thanks for your request. Not an easy question! I saw the biography of Frank at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/rusconi-francis-philip-frank-8299, and it seems Neuchatel is a key place. So the only thing I can recommend is to take up contact with various authorites in this beautiful city, built of the golden “Pierre Jaune”. Good luck!

Dear Per

Im researching a stone mason Francis Philip Rusconi who is famous in Australia for opening up the Borenore quarry at Orange NSW (used in Sydney bldgs) and who was apprenticed in Switzerland by his mason father Pietro Rusconi by age 15 (1889-1900) at Neuchatel, and also at verquinto, Italy. Francis did work from Switzerland on the StMarie Cathedral altar Paris, and Westminster Abbey staircase etc. Could you recommend how best to go about findng information on Francis and his work?

Pingback: Miszellen | www.stone-ideas.com