The famous Chisel quarry, a vital part of Chephren’s Quarry. Intact in 2014, destroyed by agricultural development in 2023. Source: Google Earth

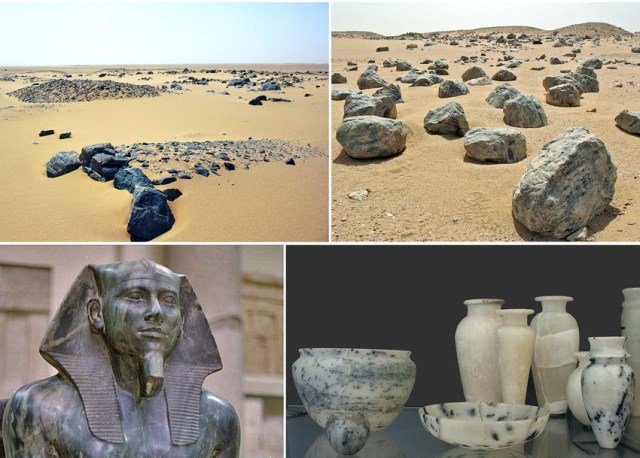

Over the last two years Chephren’s Quarry in the Western Egyptian Desert has been largely destroyed by the Toshka Megaproject. Providing tens of thousands of fine, bluish hardstone vessels and superb statuary almost 5000 years ago, the quarry is among the most special ones from Ancient Egypt. As the world’s oldest, large-scale quarry for sculpture and stone vessels, it covers an area of roughly 50 square kilometres of boulder terrain in the flat desert west of Abu Simbel, and has been at risk from the Toska Megaproject since the 1990s. This enormous land reclamation project was initiated in order to use water from Lake Nasser for producing wheat and other crops in the region’s hyper arid environment and make Egypt less dependent on imports for feeding a rapidly growing population.

Chephren’s Quarry was discovered in the 1930s. In the 1990s modern archaeological investigation was started by the University of Liverpool, a project that was widened to an archaeological rescue survey by 2002, partly financed by the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage. Monitoring ran until 2007 by the EU-funded QuarryScapes project, which was headed by the Geological Survey of Norway, in close cooperation with the Egyptian heritage and geological authorities. Since then, the site has been monitored by the heritage authorities.

Chephren’s Quarry, southern Egypt: Above, quarry sites now destroyed, and below, examples of sculpture and vessels. Photos by Per Storemyr; statue of King Chephren by Jon Bodsworth (Wikipedia).

The quarry landscape

A staggering 700 individual quarries, plus an array of associated elements of infrastructure, such as living quarters, wells and transportation networks, was mapped during several campaigns from 1999 to 2007. The intricate organisation of quarrying came to life, aimed at providing delicate stone vessels and statuary to pyramids and temples. A very special gneiss was the target, and it was clearly the bluish colour of the stone that made it so attractive that operations in this remote area, 1200 km south of Giza, was sustained for centuries.

Chephren’s Quarry is the world’s oldest large-scale quarry for sculpture and stone vessels. Now the fine statue quarry on the picture is entirely destroyed by the Toshka Megaproject. Photo by Per Storemyr

But individual quarries are modest. This is because stone is rather scarce in the flat desert landscape. It is a weathered-down boulder terrain, which implies that groups of small and large boulders were split, often by fire, and worked by locally procured stone tools to blanks that were transported down the Nile and finished in special workshops in Aswan and elsewhere. This mode of quarrying means that we are left with hundreds of “holes” in the ground, surrounded by left-over stones and thousands of spoil heaps from the works.

The Toshka Megaproject

Building of canals for diverting Nile water from Lake Nasser started already in the 1970s. A New Valley running parallel to the Nile in the Western desert was envisaged – a green corridor for much-needed crop production – and for habitation. Surely, such a megaproject met many obstacles, political, environmental, technical, and financial. Thus, the project came to a halt several times and by 2012, at the time of the Arab Spring, it was considered a gigantic failure.

However, by 2021 extensive works resumed in the Toshka area, close to Chephrens Quarry. Very little of the ancient quarry landscape had been affected by the project until then. But with the rapid pace of the project over the last two years, also connected to the wheat supply crisis due to the war in Ukraine, most of the quarry landscape is now gone forever.

Only about 10-20% of the archaeological remains are left, and, fortunately, this includes an important part of the quarries, at the so-called Quartz Ridge and environs. Also the nearby Stele Ridge carnelian mine has been partly preserved. Judged from satellite images, there are few indications that they will be destroyed in the very near future. Other key sites, for example Chisel Quarry, Khufu Stele Quarry and not least archaeological remains along the 50 km long ancient track to the Nile are now entirely transformed to modern agricultural production areas.

Images from Google Earth showing the development at Chephren’s Quarry between 1997 and 2023. Red polygons mark clusters of ancient quarry and other archaeological sites (source: the QuarryScapes project). The scale of each image is c. 50 km across.

Food security vs. heritage values

Controlled by the armed forces of Egypt, the Toshka Megaproject may seem an understandable endeavour to secure food production for a rapidly growing population. Whether it is a sustainable project in the long run is, of course, debatable, given that this is one of the driest spots on earth and that Nile water rights may not be easy to handle in the future. The project affects ecology and politics of a vast region.

Aerial view of part of the land reclamation in the Toshka project, giving an impression of the layout. Screenshot from Egyptian promotion video. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4C0u1h4DCTE

For the region is vast. Some 6000 square kilometres are already being reclaimed for agricultural production in the Toshka area, and tens of thousands of square kilometres may follow. Hence, one may ask why it is not possible to actively preserve Chephren’s Quarry and, of course, other archaeological sites in the region. They comprise small areas as compared to the size of the land reclamation projects, and they are imbued with unique values.

It is a sad development, also considering that destruction of “less famous” archaeological sites is going on at an alarming rate all over Egypt. There are better ways, but they require recognition of heritage values and multidisciplinary work and planning on quite another scale than today.

The famous Chisel quarry, a vital part of Chephren’s Quarry. 2014 and 2023. Source: Google Earth

Khufu Stele Quarry, a part of Chephren’s Quarry, was destroyed by agricultural developments between 2021 and 2023. Images from Google Earth. Scale in the foreground about 500 m.

Further reading

Risk analysis and destruction of Ancient Egyptian quarries, including Chephren’s Quarry

- Storemyr, P. 2009. Whatever Else Happened to the Ancient Egyptian Quarries? An Essay on Their Destiny in Modern Times. In: Abu-Jaber, N., Bloxam, E., Degryse, P. & Heldal, T. (eds.): QuarryScapes. Ancient stone quarry landscapes in the Eastern Mediterranean, Geological Survey of Norway Special Publication 12, 105-124. Download PDF (4,1 MB)

- Storemyr, P., Bloxam, E. & Heldal, T. (eds.) 2007. Risk assessment and monitoring of ancient Egyptian quarry landscapes. QuarryScapes report, Geological Survey of Norway, Trondheim, 207 p. Download PDF (12 MB)

Archaeology of Chephren’s Quarry

- Heldal, T., Storemyr, P., Bloxam, E. & Shaw, I. 2016. Gneiss for the Pharaoh: Geology of the Third Millennium BCE Chephren’s Quarries in Southern Egypt. Geoscience Canada, 43, 63-78. More info at my academia.edu-site

- Shaw, I., Bloxam, E., Heldal, T. & Storemyr, P. 2010. Quarrying and landscape at Gebel el-Asr in the Old and Middle Kingdoms. In: Raffaele, F., Incordino, I. & Nuzzollo, M. (eds): Proceedings of the First Neapolitan Congress of Egyptology. Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, Naples, 200-218. View online at academia.edu

- Heldal, T., Storemyr, P., Bloxam, E., Shaw, I., Lee, R. & Salem, A. 2009. GPS and GIS Methodology in the Mapping of Chephren’s Quarry, Upper Egypt: A Significant Tool for Documentation and Interpretation of the Site. In: Maniatis, Y. (ed.): ASMOSIA VII, Proceedings of the 7th International Conference of the Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity, Thassos 15-20 September 2003, Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique supplement, 51, 227-241. PDF

- Heldal, T. & Storemyr, P. 2003. Chephren’s Quarry, Upper Egypt: Archaeological registration and mapping of ancient quarry sites. Geological Survey of Norway, Report No. 2003.025, 43 p. Download PDF (0,6 MB)

Development of the Toshka project in recent years

- Toshka Project, Egypt (timelapse of satellite photos). 2023. https://eros.usgs.gov/earthshots/toshka-project-egypt

- Toshka agricultural project revived amid Egypt’s hope to achieve self-sufficiency in wheat. 2022. https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/1/115145/Toshka-agricultural-project-revived-amid-Egypt%E2%80%99s-hope-to-achieve-self

- Toshka: reclaiming land for sustainable use. 2023. https://wilo.com/en/Pioneering/Stories/Toshka-reclaiming-land-for-sustainable-use-_28417.html

- Why did Egypt revive the Toshka Project after it stopped in Mubarak era. 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9bBVETvEVvE

Discover more from Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology & Conservation

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.