Heavily bioeroded/bored European flat oyster shell from a shallow bay at Flosta, South Norway (c. 9 cm long). Photo by PS

Looking closely at shells on the beach, you will find that most have smaller and larger holes, tunnels and “galleries” made by boring organisms. This is bioerosion, a powerful part of the process that makes shells break down and eventually become part of a shell sand deposit. Along the coast of Norway, such deposits were sometimes dug for aggregate to make lime mortars for building medieval churches. And bioerosion of shell fragments in the mortars can still be seen under the microscope. It may aid the understanding of how the mortars were made.

Everyone knows the shipworm, the strange bivalve shell that bores through the wooden hull of a ship or the timber shafts of a quay to make a living – and so destroys the wood. Except for one special type, shipworms don’t bore through hard calcium carbonate, such as limestone, marble and shell. But there are many other organisms that specialize in doing just so.

Shipworm borings in driftwood at the outer coast of Tromøy, South Norway. Photo by PS

Earlier this year I wrote a small article on bioerosion on the Adriatic coast, showing how bivalves, limpets, barnacles, sponges and algae/cyanobacteria contribute to shaping the coastline by boring into the limestone. Since there is hardly any limestone (or marble) along the rocky coast of South Norway, where I live, I had to start looking at shells on beaches and in shallow bays to find similar phenomena.

Shells on beaches and in shallow bays

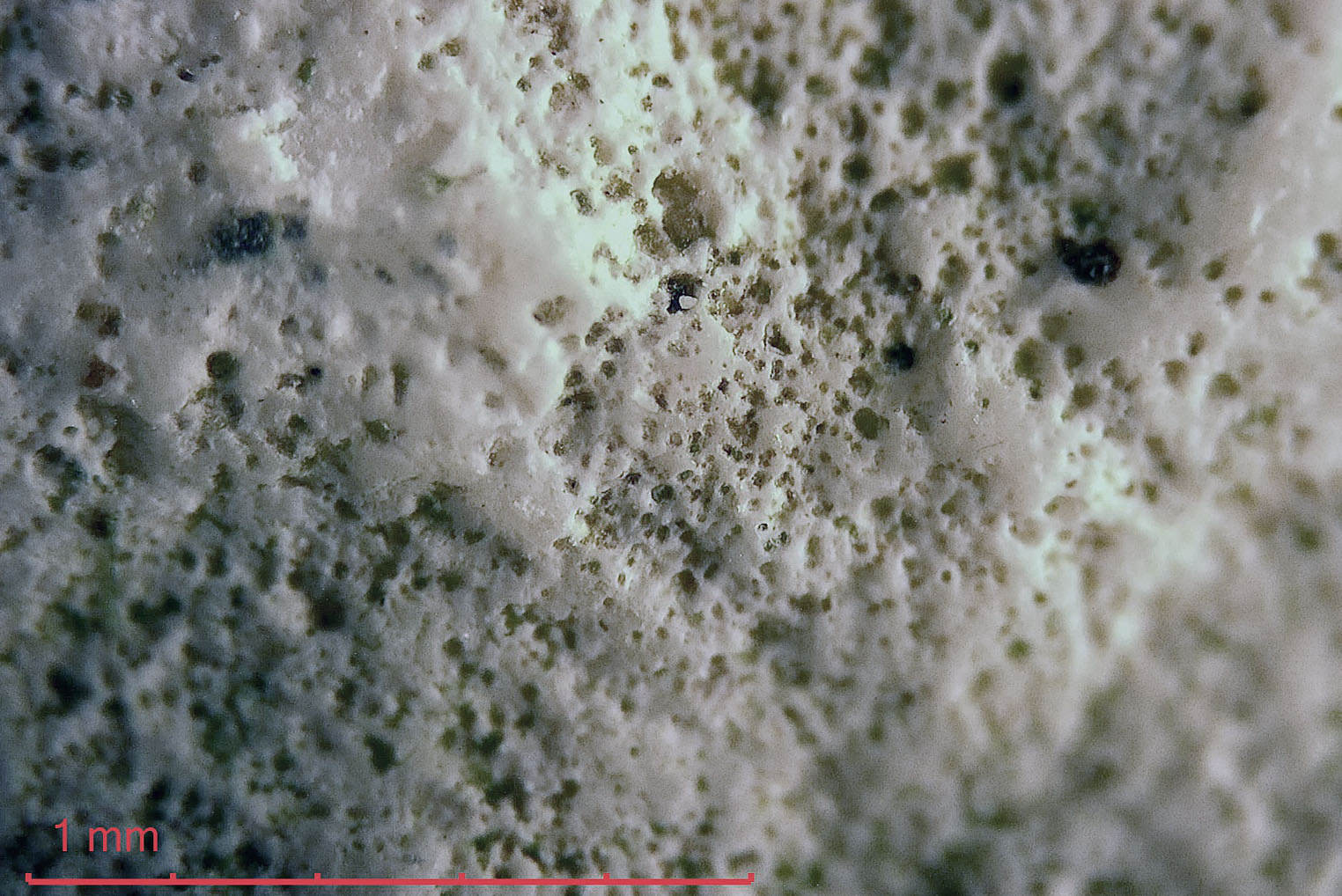

Walking along the beaches, there are lots of shells, for example cockles that look “fresh” at a distance. But on closer inspection it is evident that they have lost their lustre, they are slightly eroded from moving with the waves on the sand and they are full of microscopic holes bored from the surface inward. This is biopitting, normal also on limestone, and presumably caused by algae/cyanobacteria.

Cockles on the beach at Hove, Tromøy in South Norway. Photo by PS

Surface of a cockle shell with small holes of biopitting barely visible. Width of field 10 mm. Photo by PS

Biopitting on cockle shell under the microscope. Photo by PS

In shallow bays with muddy ground, bioerosion is more pronounced. Shells of European flat oyster, blue mussel, scallop and other species are often heavily bored, but for me it is difficult to understand who is responsible. Worms may be at work, perhaps small gastropods, maybe sponges? Scraping barnacles may also contribute, the latter of which are sometimes attached to shells. In addition, shell surfaces are usually strongly biopitted and there are lots of small worm tubes, “tunnels” of micritic (microcrystalline) calcite made by worms for their own protection.

Larger borings and biopitting on an European flat oyster shell. Width of field 10 mm. Photo by PS

Borings extending to gallery in a European flat oyster shell. Width of field 12 mm. Photo by PS

Worm tube and other secondary, micritic lime deposits on an oyster shell. Width of field 12 mm. Photo by PS

Borings in a blue mussel shell. Width of field 15 mm. Photo by PS

Shell bioerosion in the literature

These observations inspired a look into the literature on shell bioerosion, as well as micritization. The latter often follows bioerosion and may be a part of it, involving the transformation of the crystalline fabric of shells to a microcrystalline and porous one, without the shell necessarily losing its general form. The same happens to corals and many other species with carbonate shells or skeletons. It is part of the early diagenesis (rock forming process) of carbonate rocks.

This has become an important field of research because it involves dissolution and reprecipitation of carbonates and thus aspects the global carbon cycle, but also of development of porosity in petroleum reservoir rocks (Garuglieri et al. 2024). It is a complex field of research, with quite some differences between warmer and colder oceans. In northern seas, e.g. Skagerrak, it was pioneered by Torbjörn Alexandersson (1972, 1978). There are also studies in shallow waters along the Scottish coast (Akpan & Farrow 1985) and as far north as Finnmark (Bromley et al. 1981). Mention is also made of bioerosion and micritization in beach rock (Nagy & Dypvik 1984).

Generally, at our latitudes, the studies show that holes made by boring organisms are very common, indeed, whereas it has been more difficult to explain micritization. Microorganisms may be at work, but also inorganic mechanisms of dissolution and reprecipitation, as well as changes from aragonite to calcite. Aragonite is a common mineral in shells and a less stable variety of calcium carbonate than calcite.

Such observations are confined to shallow marine environments. If shells become part of a terrestrial deposit, their rate of decay may increase depending on the actual environment, for example regarding acidity (higher pH enhancing dissolution), availability of microorganisms, larger boring organisms and animals. Living terrestrial gastropods have been seen to scrape or bore on their dead ancestors to build their own shell (Cadée 1999, 2016).

A bioeroded small gastropod, 20 mm across. Photo by PS

Shell fragments from a gravelly beach by Stavern, South Norway. On close inspection, almost every fragment shows traces of bioerosion. Width of field: c. 30 mm. Photo by PS

Shell sand is characterized by diversity of shell types. From Korshavn at Flosta, South Norway. Photo by PS

Shell sand for aggregate and marble for lime burning

There are quite a few medieval churches along the Norwegian coasts and fjords that have lime mortar with aggregate dug from shell sand deposits, or perhaps even from active sandy/gravelly beaches. Aggregate is what you mix with the lime binder to make the mortar workable. Two of these churches are Sakshaug Old Church in Central Norway and Moster Old Church on the west coast, both built in the 12th century.

Shell fragments from bivalves, gastropods and foraminifera in a medieval mortar from Moster Old Church. On the larger fragment in the middle, tiny holes (biopitting) from microboring organisms can be spotted. Width of field c. 8 cm. Photo by PS

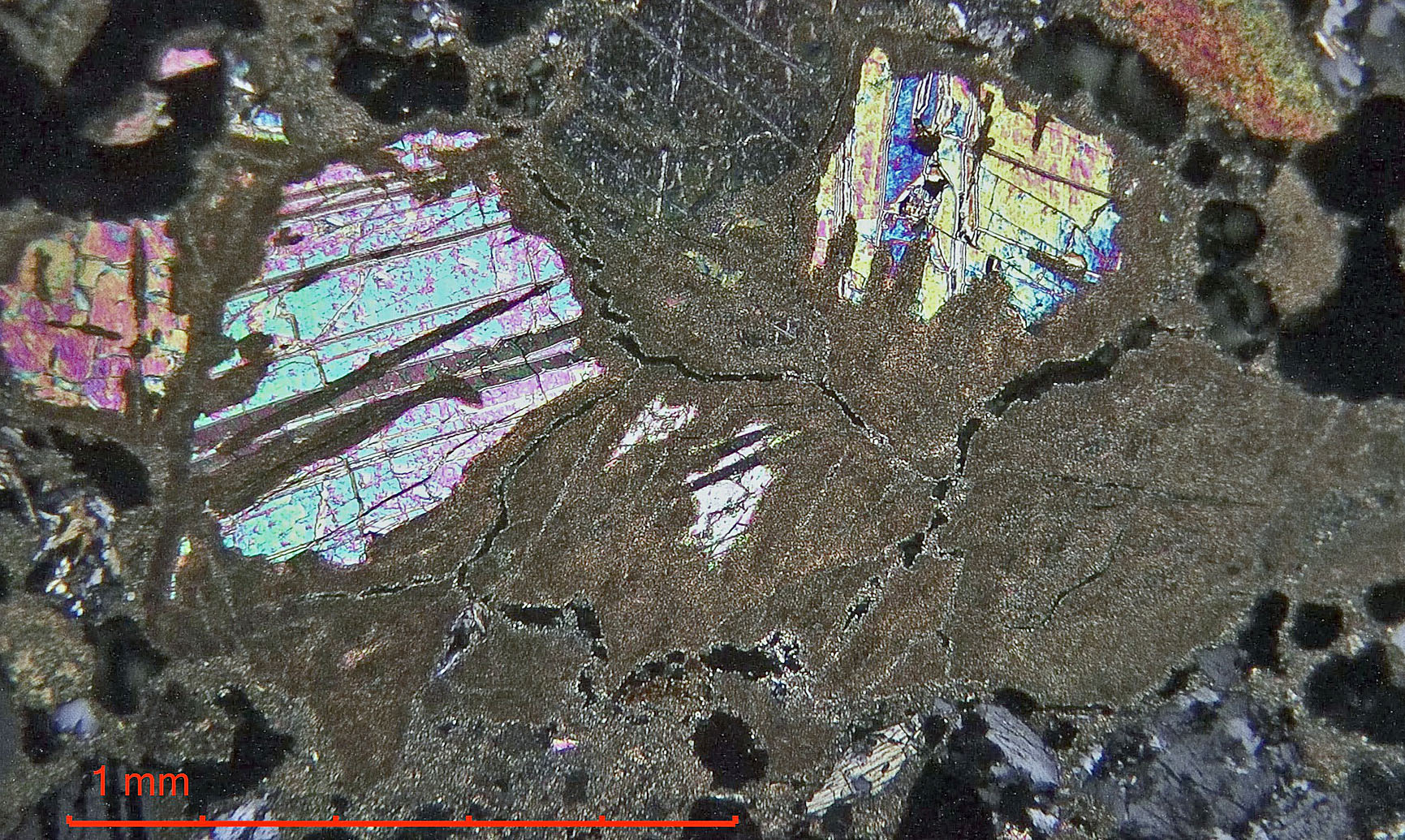

Both churches have aggregate with a high proportion of shell fragments, but also including rock and mineral grains. And in both cases, as in many others along the coast, the lime binder was burnt from local marble. One can easily spot typical unburnt – or “underburnt” – marble fragments on studying thin sections of mortar samples with a polarizing microscope. Such fragments did not get the required 850°C in the crude, old kilns to become entirely calcinated. And so they are preserved because they could not be slaked to binder on making the mortar.

There are marble lime burning traditions reaching far back close to both churches. Marble was the most important raw material for lime burning along the Norwegian Atlantic coast – simply because of geology (Storemyr et al. 2023). This is quite different from what happened elsewhere in the North Atlantic region. For on the isles north of Scotland and the Faroes, but also on the west coast of Denmark, lime was historically often burnt from shell. These are places that are often, but not always, poor in bedrock lime resources (Thacker 2017, 2019, se also overview in Storemyr & Arting 2024).

Sakshaug old church in Central Norway. Photo by PS

Old lime mortar with shell sand aggregate in Sakshaug old church, Central Norway. Photo by PS

Underburnt marble fragment in mortar at Sakshaug old church, Central Norway. The colorful areas are remains of “fresh” marble. Microphoto (XPL) by PS

Bioerosion in shell aggregate

Typically, the shell fragments in both Moster and Sakshaug old churches are small, usually much less than 10 mm. The largest fragments belong to bivalves and gastropods, while there is a range of fragments from smaller gastropods, foraminifera, as well as barnacles and spines from sea urchins.

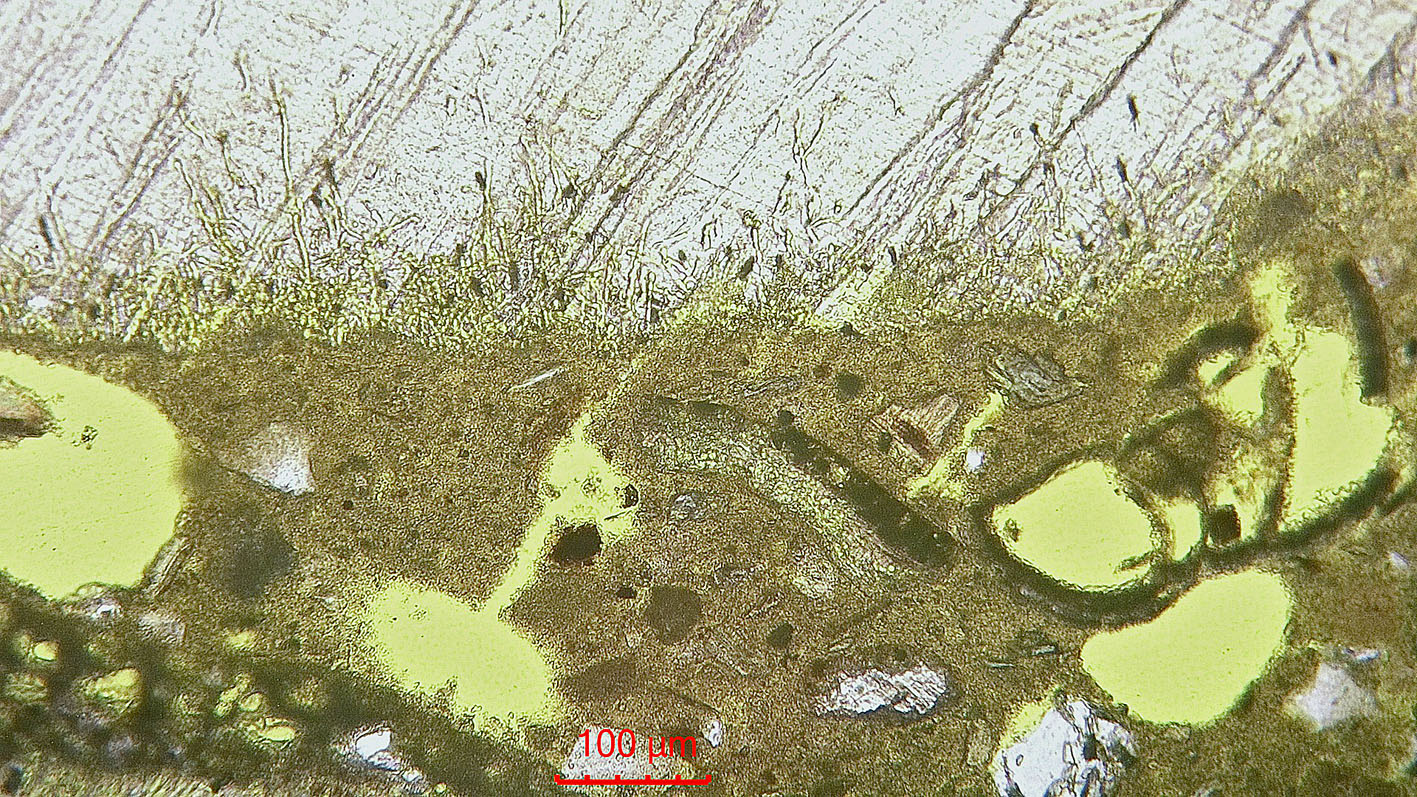

It comes as no surprise that the fragments are loaded with holes from boring organisms. Since the fragments are so small, traces of larger boring organisms cannot be seen, and there are generally holes within two size classes – in the range of 20-50 micrometres (<0,05 mm) and less than 5 micrometres.

The bigger ones are akin to biopitting surface holes seen on shells on the beach. But holes with a similar size are also cutting along the fabric of the shells to form “galleries”. Could cyanobacteria have been responsible? Often very finely crisscrossing or “tunnelling” entire shell fragments, the smaller ones are different, and I don’t know what kind of microorganisms that have been at work here. Perhaps cyanobacteria, as well?

Larger borings in dark, micritic part of shell fragment (middle). Moster old church. Microphoto (PPL) by PS

Larger borings in a shell fragment. Sakshaug old church. Microphoto (XPL) by PS

Larger borings in the dark part of the shell and very fines ones in the light. The edge (top) is micritic with borings. Moster old church. Microphoto (PPL) by PS

Very fine borings from the edge of a shell fragment. Moster old church. Microphoto (PPL) by PS

Crisscrossing, very fine borings in a shell fragment. Sakshaug old church. Microphoto (PPL) by PS

Micritization of shell fragments

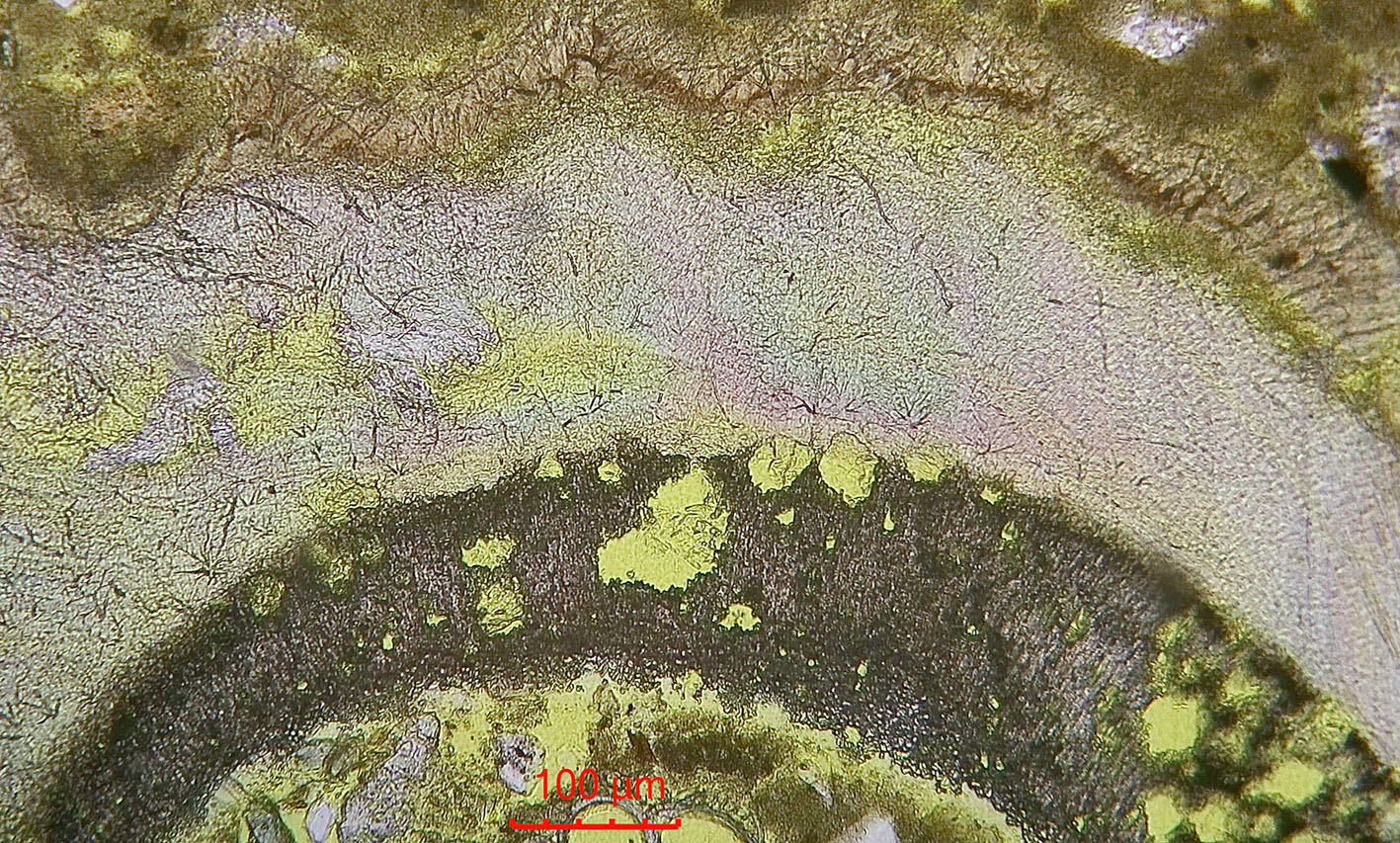

The holes and tunnels all seem to be empty. This implies that microorganisms did not leave any micritic lime within. However, many shells with microborings have turned fully or partially micritic, often in such a way that they blend almost entirely into the mortar binder, which also consists of micritic calcium carbonate, but of course man-made!

The observation is in line with the general knowledge on micritization of shells, though it is not known exactly which mechanisms that are responsible for the process.

Microbored and micritized shell fragment that seamlessly blends into the binder of the lime mortar. Moster old church. Yellow represents pores and borings. Microphoto (PPL) by PS

Partially micritized fragments of barnacle (top left) and shell (middle) surrounded by a thin layer of lime binder. Black represents pores. Sakshaug old church. Microphoto (XPL) by PS

Burnt and unburnt shell

Recalling that burning of shell to make lime once was an important tradition in the North Atlantic region, the shells burnt were of course much larger than tiny gastropods and foraminifera. Sturdy cockle was often the shell of choice.

But in Norway marble was by far the most important lime raw material along the Atlantic coast, as was limestone in the south-east of the country. Yet, there are a few regions with little or no marble and limestone in the bedrock. Thus, one cannot rule out that some Norwegian churches were made – or repaired – with lime based on burning shell, such as cockles and perhaps European flat oysters.

In cases where there are no underburnt marble or limestone fragments to determine the origin of the lime binder, several methods can be used for finding an answer. “Shell-limes” may, for example, have different chemical signatures than “marble-lime” and “limestone-lime”. In this little article it has been shown that an additional tool for investigation is observation of shells under the microscope. It can be used for screening larger amounts of samples.

For, to sum up the observations, as a hypothesis: When shell fragments in a mortar are diverse, generally small and show overwhelming evidence of bioerosion, it is unlikely that they have been part of lime burning. Burning would have destroyed many bioerosion traces and thus the shell fragments were rather added to the mortar as aggregate – just as in the cases of Moster and Sakshaug old churches.

Section of sea urchin spine in lime mortar from Sakshaug old church. Microphoto (XPL) by PS

This article is partially based on samples taken during conservation campaigns with Fabrica and other partners at Moster and Sakshaug old churches (2022-2025), including building archaeological studies and stratigraphy of mortars. Thanks to the National Trust of Norway, that owns both churches, and the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage, for permission to take mortar samples.

Last update 28.12.2025

References

Akpan, E.B. & Farrow, G.E. 1985. Shell bioerosion in high-latitude low-energy environments: Firths of Clyde and Lorne, Scotland. Marine Geology, 67, 1-2, 139-150

Alexandersson, T. 1972. Micritization of carbonate particles: processes of precipitation and dissolution in modern shallow-marine sediments. Bull. geol. Inst. Univ. Upsala N. S. 3, 7: 201-236

Alexandersson, T. 1978. Destructive diagenesis of carbonate sediments in the eastern Skagerrak, North Sea. Geology, 6 ,6, 324–327

Bromley, R.G. & Hanken, N.-M. 1981. Shallow marine bioerosion at Vardø, arctic Norway. Bull. Geol. Soc. Denmark, 29, 103-109

Cadée, G.C. 1999. Bioerosion of shells by terrestrial gastropods. Lethaia, 32, 3, 253–260.

Cadée, G.C. 2016. Decay rate of shells in aquatic and terrestrial habitats, some comments. Basteria, 80, 4-6, 193-194

Garuglieri, E., Marasco, R., Odobel, C., Chandra, V., Teillet, T., Areias, C. et al. 2024. Searching for microbial contribution to micritization of shallow marine sediments. Environmental Microbiology, 26, 2, e16573

Nagy, J. & Dypvik, H. 1984. Lithified Holocene shallow marine carbonates from Nesøya, North Norway. Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift, 64, 121-133

Storemyr, P. & Árting, U. 2024. The Stones and Mortars of the Faroese Medieval Cathedral. In Eliasen, K.S. & Stige, M. (eds.) The Cathedral of Kirkjubøur and the Medieval Bishop’s See of the Faroes. Tórshavn: Tjóðsavnið, 301-328

Storemyr, P., Granmo, T. & Berner, T. 2023. Småskala kalkbrenning. Geologisk mangfold i kulturminnevernets tjeneste. Fortidsminneforeningens årbok, 177, s. 53-76

Thacker, M. 2017. Constructing lordship in North Atlantic Europe: the archaeology of masonry mortars in the medieval and later buildings of the Scottish North Atlantic. PhD-thesis, 3 volumes, The University of Edinburgh

Thacker, M., Hughes, J., & Odling, N. 2019. Animal, vegetable or mineral? Characterising shell-lime, maerl-lime and limestone-lime mortar evidence from the Late Norse and Medieval site of Tuquoy, Orkney. In J. I. Alvarez, J. M. Fernandez, I. Navarro, A. Duran, & R. Sirera (Eds.), Proceedings of the 5th Historic Mortars Conference, RILEM Proceedings PRO 130, 758-777

Discover more from Per Storemyr Geoarchaeology & Conservation

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Miscellanea: Metro station for the Colosseum in Rome