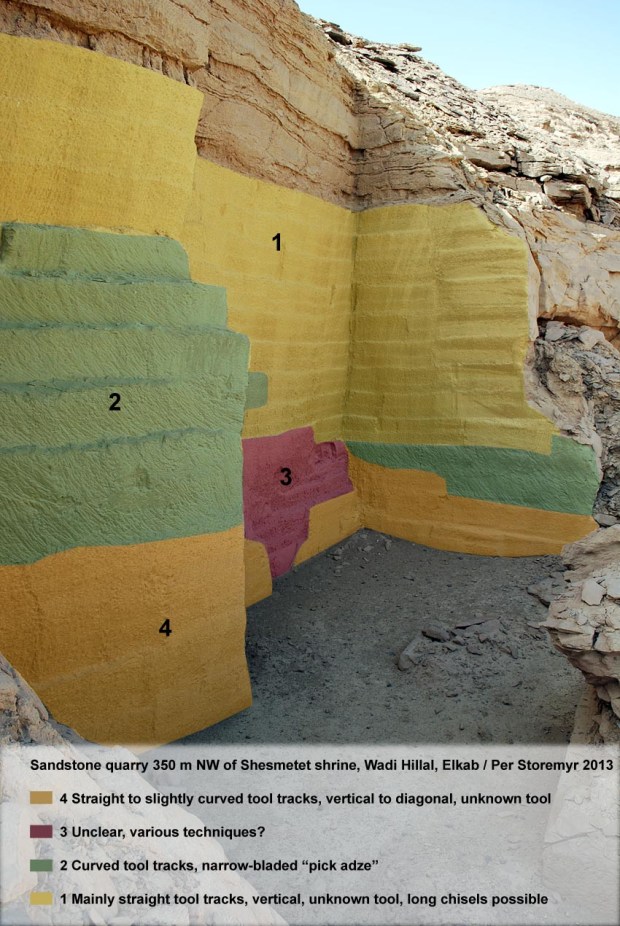

Fact, no fiction: Evidence for the use of pickaxes with a narrow blade forming the cutting edge. Quarry by Shesmetet temple in Wadi el-Hillal by Elkab in Upper Egypt. Photo: Per Storemyr

Ancient Egyptian quarrying of softstone, such as sandstone and limestone, is commonly described as having been done exclusively by chisels struck with wooden mallets, even through the Roman period. In this way trenches separating each block were made, and then the block was loosened at the underside with various types of wedges. But this is not the end of the story. In this article I will show – perhaps the first – indisputable evidence that pickaxes were also used, albeit possibly on a minor scale.

One of the most common tool traces in Ancient Egyptian limestone and sandstone quarries form long, straight lines that beautifully define numerous quarry walls and separation trenches, generally from the New Kingdom on.

Typical appearance of separation trenches in Ancient Egyptian sandstone quarries, with long “chisel tracks”. From the west bank at Gebel el-Silsila. Uncertain dating, but probably Graeco-Roman. Photo: Per Storemyr

Few have seriously doubted that these parallel lines derive from medium to long chisels, usually with a narrow blade forming the cutting edge. In their book “Stones and Quarries in Ancient Egypt” (2008), based on “Steine und Steinbrüche im Alten Aegypten (1993), Rosemarie and Dietrich Klemm even introduced a chronology of quarrying based on differences they observed in preserved chisel marks, or rather the tracks that the chisels left on the rock. They also went beyond the long, parallel marks and included other types of marks from the Old and Middle Kingdom in their chronology, which simplified looks like this (p. 194ff, 2008-edition):

- Old and Middle Kingdom: Short, irregular tool tracks, from the use of short, relatively soft copper chisels.

- Early New Kingdom: More regular and slightly longer tool tracks, typically forming a herringbone pattern, from the introduction of harder bronze chisels.

- New Kingdom to Late Period, from the 19th Dynasty on: Regular, almost parallel, long tool tracks, from the introduction of longer bronze chisels.

- Ptolemaic and Roman period: Very regular, parallel, long tool tracks, from the introduction of harder iron chisels.

This chronology has since become a widely cited standard reference to the tools used in Ancient Egyptian quarrying. Though it is difficult to dispute the general development from the New Kingdom on, some researchers read another story from especially the early tool marks, starting by Somers Clarke and Reginald Engelbach in their “Ancient Egyptian Construction and Architecture” from 1930. They found that many tool marks in the Old and Middle Kingdom were rather consistent with the use of pickaxes held with both hands, which typically creates curved tool tracks (p. 17). Dieter Arnold in his “Building in Egypt” (1991) went a few steps further and suggested that “pointed stone picks or axes were used during the Old and Middle Kingdoms” (p. 33).

Though the suggestions, especially as regards the Old and Middle Kingdoms, can only be substantiated or rejected through detailed studies and experimentation, they are valid contributions to a possible much more complex development in tool use than Klemm and Klemm have proposed. From another perspective, it is indeed odd that that the use of long chisels had such a strong position even into the Ptolemaic and Roman periods. For elsewhere in the Graeco-Roman world, the pickaxe had become the standard tool for cutting trenches in softstone and marble; it may have started already with the Minoans, as reviewed by Waelkens, De Paepe and Moens in “The Quarrying Techniques of the Greek World” (1990).

Small quarry close to Shesmetet temple in Wadi el-Hillal by Elkab, showing marks of both chisels and pickaxes. Photo: Per Storemyr

All these investigations and discussions were not on my mind back in 2010, as I was on an entirely different type of fieldwork with the Belgian Archaeological Mission to Egypt. But on a free day, I was so lucky as to bump into a small sandstone quarry close to the Ptolemaic temple of Shesmetet in Wadi Hillal by Elkab in Upper Egypt. Climbing up to the quarry, there were the standard, long straight tool tracks so widely seen in Egypt, but it was another type of tracks that caught my attention; large parts of the quarry walls covered with strongly curved tracks, fully consistent with the use of a pickaxe.

Curved tracks of pickaxe in a corner at the Shesmetet quarry (top). The quarryman needed to turn round to remove the last bit of stone (marks to the right of the scale). This is very typical in quarries were picks have been used to make separation trenches, for example in the Berne area in Switzerland (bottom, 19th century). Photos: Per Storemyr.

On closer inspection of the well-preserved quarry walls, it could be seen that a pickaxe with an adze-like, narrow blade had been in use, each cut measuring 10 cm or more in length. But it was in the corners that the evidence became most striking. For it is difficult to cut a straight trench-corner with a pickaxe, so normally the quarryman would turn round, with his back to the quarry wall to cut the last bit of rock away. And this was exactly what could be seen in the Shesmetet quarry. It is just like it can be observed in numerous much later quarries, where the use of pickaxe is very well documented, for example in 19th century sandstone quarries around Berne in Switzerland (see this blog post).

Chisel marks in a separation trench in a small, probably Graeco-Roman quarry at Qubbet el-Hawa by Aswan. Note the “stepped” appearance, with many small “humps”. These are the result of each impact of the chisel when it is driven down through the rock with a mallet. Photo: Per Storemyr

The difference between chisel tracks (top) and marks from pickaxe (bottom) in the quarry by Shesmetet temple. Photo: Per Storemyr

Separation trench made by pickaxe in the sandstone quarries at Gebel el-Silsila (west bank). Photo: Per Storemyr

Not only were the tool tracks in the little quarry long and curved, they were also very “smooth”, in contrast to chisel tracks, which form long series of closely spaced small “humps”. These are the result of each impact of the chisel when it is driven down through the rock with a mallet.

Arguably, the quarry is the result of one relatively short operation only, driven down as a series of platforms in the hillside. This is because the marks of the pickaxe are found in a belt between straight tool tracks, as the preliminary map at the end of the article shows. At the bottom, representing the last phase of quarrying, there are long, often slightly diagonal “chisel tracks”; then come the tracks of the pickaxe and at the top, where it all started, there are again the straight tracks, now forming quite vertical, parallel tracks.

The quarry has not been dated, but, especially given its proximity to the Shesmetet temple, it is most likely from the Ptolemaic period. But Wadi Hillal has monuments stretching back to the New Kingdom and beyond, so we cannot be entirely certain about the dating. A search for diagnostic ceramics and inscriptions thus ought to be undertaken.

Satisfied with the discovery, I didn’t think much about the quarry before recently going through my photo archives. And there was another “discovery” waiting. For back in 2002 I had, indeed, seen similar marks of pickaxes at the western part of the famous Gebel el-Silsila quarries. What was more; I had photographed a half-finished separation trench made with a pickaxe. The trench, 10-15 cm wide, was made in a “standard” way, with two parallel, curved tracks cut out in order to knock off the middle part with a heavy blow. Moreover, the type of pickaxe appears to be similar to what was observed by Elkab, featuring a narrow blade forming the cutting edge.

This particular part of the Silsila quarries has neither been dated, but is generally considered to have been in operation between the New Kingdom and Greaco-Roman period.

Whatever the dating, it should be clear by now that there are variations in tools used for cutting separation trenches in Ancient Egyptian softstone quarries, and that the pickaxe must have been in use at least by the Ptolematic period, if not earlier. This said, there can be little doubt that the straight “chisel tracks” are dominating from the New Kingdom on. But we still don’t know exactly what kind of long chisel tool that was applied and how it was put in use to form such terribly straight tracks. But this is another story.

Thanks to Jim Harrell and Maria Nilsson who indirectly gave me the impetus to put together this article.

Other articles on this website dealing with softstone quarrying:

- Experimental archaeology: The traditional way of quarrying soapstone

- With pickaxe into modern times: Quarrying of Bernese sandstone (CH)

- With pickaxe into modern times II: Quarrying of Marés at the Balearic Islands

Map of the quarry

Preliminary map of the quarry by Shesmetet temple, showing the various tool marks that can be seen at the quarry walls. Map: Per Storemyr

Location map

Pingback: Tusen år med brytning av kleberstein tok nettopp slutt. En historie om mekanisering og globalisering. Og om å gjenoppdage gammelt håndverk | Per Storemyr Archaeology & Conservation

Pingback: Em Hotep Digest vol. 02 no. 07: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt

Pingback: Appunti brevi - Stone-ideas.com

Pingback: Noticias breves - Stone-ideas.com

Pingback: Kurz notiert - International magazine for architecture and design with natural stone | International magazine for architecture and design with natural stone

Pingback: Notas e Agenda - International magazine for architecture and design with natural stone | International magazine for architecture and design with natural stone

Pingback: Briefly noted - International magazine for architecture and design with natural stone | International magazine for architecture and design with natural stone