Rock art by a “fjord” along the Nile? This is how Wadi Abu Subeira may have looked like at the time of the making of the Late Palaeolithic rock art, some 15-20.000 years ago. The iron mining concessions that may destroy the rock art are also indicated. Hypothetical reconstruction by Per Storemyr based on information on rock art locations from Adel Kelany and on the general knowledge of the geomorphology in the area, provided in Wendorf & Schild (1989). Only field studies can confirm the hypothesis.

Since the publication of the threats to the Palaeolithic rock art in Wadi Abu Subeira three weeks ago, there has been much response through e-mail and social media, and the case has been covered by many online magazines and blogs. People in Egypt and elsewhere are concerned, and I wish to thank you all for your interest and for bringing the case along to friends and colleagues, as well as to administrators and politicians. There now seems to be a need for an “unbiased”, comprehensive overview of what is actually known about the landscape, the archaeology, the rock art, the threats, current conservation efforts and options for the future. The overview below is based on published literature, and information that otherwise belongs to the public sphere. It is written in close cooperation with Adel Kelany, and we have benefitted from input by Dirk Huyge.

Content

This is a comprehensive article – here’s an overview:

- Location and current infrastructure

- Geology, climate and wildlife

- History of archaeological survey

- Summary of known and anticipated archaeological sites

- Threats to the archaeology

- Conservation efforts

- Future protection

- A vision – World Heritage Site

- Sources

- Maps

Location and current infrastructure

Wadi Abu Subeira (or Chor [Khor] Abu Subeira) is a 60 km long and up to 1 km broad wadi in the Eastern Desert of Egypt. It has many small side-valleys and enters the Nile about 12 km north of Aswan, or 650 km south of Cairo. Historically, the wadi was an important gateway from the Nile Valley to the Eastern Desert and the Red Sea, and in more recent centuries it has particularly been frequented by the Ababda Bedouins.

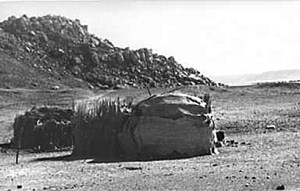

Campsite of Ababda Bedouins in Wadi Abu Subeira in the early 1980s. The rock art site CAS-6 is in the background. Development has now, 30 years later, reached to this place. Photo: Stephan Seidlmayer, with many thanks! The photo can also be found in the exhibition text “Pharao setzt die Grenzen“.

The lowermost 4 km of the wadi has now villages, agricultural fields and a major stone quarrying area at its north flank. About 40 underground clay mining operations are located along the flanks of the wadi, from the mouth and 10 km upward. Open-cast iron mineral mining takes place between 10 and 13 km from the mouth. Higher up there is little or no modern activity. There is a rough track going through the wadi, but no asphalt road. In the lower reaches there is a network of tracks for transportation of clay and iron minerals with heavy trucks. Except at the mouth by the Nile, which has been inhabited and cultivated for a long time, there was hardly modern infrastructure in the wadi until 20-30 years ago. Since fields and villages are occasionally threatened by flash flood, a security dam has been built 4 km from the mouth.

The 60 km long Wadi Abu Subeira and its location in Upper Egypt. Late Palaeolithic rock art sites are marked with green. The current iron mineral mining concessions that may destroy the rock art with red.

Geology, climate and wildlife

The wadi is located in the Nubian sandstone province of Upper Egypt and it developed along a major east-west fault line. At the steep, 50-100 m high northern flank, which is almost an escarpment, characterised by scree and rock fall, the sandstone has been altered by so-called silicification, implying that it frequently has become hard like quartzite. The southern flank is hardly silicified and not as steep as the northern flank. Iron ore, in the form of so-called oolitic ironstone, forms layers within the Nubian sandstone. This is also the case with the various types of clay.

At the time of the making of the first rock art, in the Late Palaeolithic (geologically the Late Pleistocene), some 15-20.000 years ago, it is known that the Nile River at Aswan at times ran an estimated 15 m higher than today, probably forming a braided river. This may imply that Wadi Abu Subeira at times was a shallow and narrow “fjord”, reaching several km up the wadi (9-10 km?). The occurrence of patches of Nile silt in the wadi is a testimony of the once higher Nile elevation. However, it is also a possibility that the mouth was sometimes blocked by sand dunes – and thus the “fjord” would rather have been an occasional lake (fed by ground water and occasional rain).

Towards the very end of the Late Palaeolithic (c. 12.000 years ago), a phase known as the “Wild Nile” brought exceptionally high floods. It is likely, but not yet confirmed, that extensive layers of the mineral calcite formed at the stones along the wadi flanks at this time. Such layers are found immediately below the Late Palaeolithic rock art.

The Late Palaeolithic was hyper-arid in the region, but with the beginning of the Holocene, about 10.500 years ago, a moister climate took over. This implied that the Nile eroded away the massive layers of silt that had previously been deposited. Moreover, since many wadis, including Wadi Abu Subeira, carried water at this time, previous deposits within the wadis – and remains of human activity – were also subject of erosion. Since the current arid to hyper-arid climate was established about 7.000 years ago (5.000 BC) there has been little erosion, though detrimental flash floods may occur after local, heavy rainfall in the Eastern Desert.

There is now little vegetation in Wadi Abu Subeira, but though there are, as far as we know, no trees, bushes are a main feature of the occasionally active water courses. Current wildlife has not been studied. It will certainly be rather limited, but may very well be representative of the Eastern Desert in general (ibex, gazelle, striped hyena etc.). Moreover, this part of Egypt is on very important bird migration routes, but it is not known whether Subeira constitute some kind of stop-over place.

This is also Wadi Abu Subeira: A small side valley, site CAS-2 (or KASS1), with a very rich concentration of Predynastic (3-4.000 BC) rock art. Photo: Per Storemyr

History of archaeological survey

The general archaeology of the wadi is poorly known and hardly published. It is the subject of the on-going survey by a team of archaeologists/Egyptologists with the Ministry of State for Antiquities (MSA) (formerly Supreme Council of Antiquities, SCA). The survey is headed by Adel Kelany, who is with the regional antiquities office in Aswan. Kelany is also in charge of the Mines and Quarry Department of MSA, a department that concentrates on survey and protection of the many ancient quarries and mines in Egypt. The ongoing work was launched in 2005-2006 as a rescue survey in response to the modern clay mining going on in the wadi. At the start the rescue survey focused on remains of ancient quarries, then in cooperation with the international, EU-funded QuarryScapes project. It widened to include all archaeology after the Late Palaeolithic rock art was discovered in 2006. My own field involvement has been through the QuarryScapes project and additional site visits with Kelany and team.

Leo Frobenius: One of the first to document Predynastic and later rock art in Wadi Abu Subeira. Source: Wikimedia Commons

A more limited survey of Predynastic rock art from the period 4-3.000 BC has also taken place in recent years. This has been carried out by the Aswan-Kom Ombo Archaeological Project, an American-Italian-British mission headed by Maria Gatto of Yale University. The mission has in particular concentrated on a fine ensemble of Predynastic rock art that was discovered in 1930 in a small valley at the southern side of the wadi. Generally, the occurrence of Predynastic rock art in the wadi has been made public by archaeologists and other people occasionally visiting the wadi throughout the 20th century. It was, in fact, reported already in 1892 by Greville Chester and is quite well documented by one of the famous DIAFE expeditions by Leo Frobenius in 1926. But the articles never mention images looking like the Late Palaeolithic ones.

Limited remains of Middle Palaeolithic (40-100.000 years ago) occupation close to the mouth of the wadi was excavated and reported by the Combined Prehistoric Expedition of Wendorf and Schild in the 1980s. Occasional observations indicate that there are, despite erosion, more remains of Palaeolithic occupation in the wadi, but nothing of this has been made public yet.

The work of the Combined Prehistoric Expedition in the Aswan region was concentrated to Wadi Kubbaniya, just opposite Wadi Abu Subeira, on the west bank of the Nile. The now very famous occupation sites in Kubbaniya is a grand testimony to the widespread occupation of the area in the Late Palaeolithic (c. 20-12.000 years ago), but also to earlier presence.

Palaeolithic stone tool workshop (foreground) at the northern “escarpment” of Subeira. The makers used solid quartzite bedrock for their tools. This is quite uncommon, since pebbles and lose blocks are often used as raw material for quartzite tools. Photo: Per Storemyr

Summary of known and anticipated archaeological sites

Palaeolithic occupation and quarrying (until 12.000 years ago)

I addition to the Middle Palaeolithic occupation and anticipated, more Palaeolithic occupation sites, there are extensive traces of Palaeolithic tool working along the northern wadi flank and on top of the “escarpment”. The nature and age of this tool working has not been studied, but there is reason to believe that it may reach back to the Early Palaeolithic (more than 100.000 years ago) and that it continued in the Middle Palaeolithic (Levallois cores). The tool makers took advantage of the fine, hard and colourful quartzite, like they did at several other places in Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia in these periods. It is unlikely that the tool making continued to any great extent into the Late Palaeolithic, since at this time Egyptian flint was the main stone used for tools. But quartzite may have been used to make grinding stone in the Late Palaeolithic, just as it was in Wadi Kubbaniya across the Nile (in order to process wild plants). It will, however, be very difficult to find clear Palaeolithic grinding stone workshops among the numerous such workshops from later periods (see below).

Karl Butzer in 1968 proposed that Wadi Abu Subeira, given its accessibility and iron mineral deposits, especially at the current location of iron mining (see below), would have been a logical source of red pigment (hematite, goethite) for Palaeolithic man (e.g. for body paints). This is very likely, but has not been confirmed.

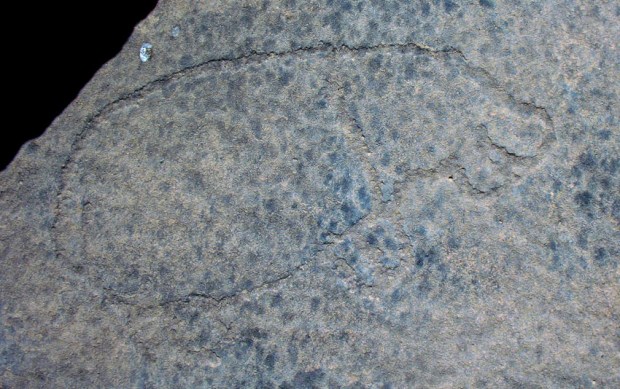

A Late Palaeolithic auroch in Wadi Abu Subeira. Note how features like edges of the rock have been used for the outline of the body. Photo: Per Storemyr

The Late Palaeolithic rock art (20-15.000 years ago)

Like the several Late Palaeolithic occupation sites in Upper Egypt, the late Palaeolithic rock art in Subeira should be seen within a group, also comprising the occurrences at Qurta close to Gebel el-Silsila, 50 km north of Subeira, as well as at el-Hosh, 10 km north of Gebel el-Silsila. Qurta is the most well-known site, with its 4 sub-sites and nearly 200 individual images. It was initially discovered by a Canadian expedition in the 1960s, but its tremendous significance as a Late Palaeolithic site was recognised a few years ago only, by the Belgian Archaeological Mission to Egypt led by Dirk Huyge. Since then intensive investigation and publication have been undertaken, culminating in a 2011-article in Antiquity, in which the Late Palaeolithic age of the rock art was confirmed by a scientific technique known as OSL (Optically Stimulated Luminescence). The occurrences at el-Hosh (at Abu Tanqura Bahari), comprising c. 35 images, are less well-known, awaiting full publication. It was found by the Belgian team in 2004.

Until now the richest site of Late Palaeolithic rock art in Subeira, CAS-6 was subject to a failed attempt at clay mining between 2002 and 2005, before it was discovered in 2006. Note the track up the hillside. Google Earth imagery.

The occurrences in Wadi Abu Subeira were first discovered by Adel Kelany and his MSA team in 2006. It was a chance find, at a place 2.5 km from the Nile (sub-site CAS-6), where modern clay mining had been attempted, but ultimately failed (Alhamdulillah!). The find was briefly published by Kelany and team with the undersigned in 2008. Since then 3 other sub-sites have been discovered by Kelany and team, sub-sites CAS-13, 14 and 20, located between 5 and 8 km from the wadi mouth. Some of these are now awaiting publication by Kelany (in press). More than 68 panels have been found as of March 2012; each panel usually have one individual image only, but many have 2 or more. Since survey is ongoing and far from completed, it is very likely that there are additional panels and images and thus it is not possible to give an exact number of individual images at the moment.

So far, all images are located relatively high up on cliffs or wadi slopes, both at Qurta, el-Hosh and Subeira. They were, in other words, made above the Late Palaeolithic level of the Nile. But whereas the Qurta and el-Hosh occurrences are mainly found in-situ on vertical cliffs, the Subeira drawings are commonly found on larger and smaller boulders that have tumbled down the wadi slope. It is anticipated that this mode of occurrence is related to specific geological/climatic events at the end of the Late Palaeolithic or later (e.g. earthquake, heavy rainfall).

Broken boulder with Late Palaeolithic rock art in Subeira: A fish (top) and a hartebeest (below, right) can be seen. Photo: Per Storemyr

The subject matter at all these sites mainly consists of aurochs, but there are also other bovids such as hartebeest and gazelle, as well as hippos and many fish images. At Qurta there are, additionally, birds, “monsters” or “hybrids” and stylized humans, whereas Subeira feature wild dog and a superbly drawn, almost life-size Nubian ibex (tracing of the latter is not yet published). This repertoire closely resembles the known wildlife of the Late Palaeolithic along the Nile.

The techniques used were hammering and incision, or a combination of the two. There are no painted images, like in the contemporary, great “Ice-Age” cave art of France and Spain. However, hammered and incised images are also known from the same time in Europe, for example the outdoor art in the Côa Valley (Portugal). Otherwise, the naturalistic style of drawing is a common trait of both the European and the Egyptian Late Palaeolithic images.

Late Palaeolithic rock art in the Côa Valley in Portugal. Note the similarity in style to Subeira – and the horse! Source: Adapted from Henrique Matos, Wikimedia Commons

In addition to age, it is mainly the similar naturalistic style that leads to questions about contact or transfer of aesthetic concepts between Europe and North-Africa in general and the Nile Valley in particular during the Late Palaeolithic. Such research has hardly begun, but will have to take account of discoveries of rather similar images near the coast of Libya and in Italy. All these images were made at the end of the last Ice-Age – at a time when the level of the Mediterranean was some 100 m lower than at present. Consequently, the ways of possible contacts may have been easier than we commonly tend to think of.

Though there is older rock art in the southern part of Africa (e.g. Blombos cave), the Late Palaeolithic group in Upper Egypt is so rich, so diverse and so well dated, that it can firmly be designated “the oldest rock art in North Africa”. And it is not exaggerated to speak of it as unique, thus true world heritage. This said, there is bound to be more, similar rock art at favourable places in North-Africa. It has just not been looked for yet.

The Predynastic and later rock art (From c. 4.000 BC)

Nothing has been published about occupation and quarry sites after the Late Palaeolithic, through the Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic (c. 10-4.000 BC) and into the Predynastic period (c. 4-3.000 BC). However, if they are not eroded away, there may very well be sites from these periods, especially since it is likely that the wadi was an important gateway to the Eastern Desert at this time.

Occupation is corroborated by the numerous Predynastic and later rock art occurrences. Three specific sites are mentioned in the literature and designated with sub-site numbers in the ongoing MSA survey. CAS-6 is located just below the Late Palaeolithic rock art at the sub-site with the same site code. It is an extremely rich rock art occurrence, mainly consisting of animals (especially cattle and ibex), but also with depictions of humans with bows and some boats. It is likely that rock art was made here almost continuously from the Predynastic and into the Middle Kingdom-New Kingdom/Nubian C-Group period. There are also much later engravings, for example of camels, and “wasm” or tribe symbols belonging to relatively recent times.

Contrary to CAS-6, site CAS-2 (also named KASS1), has been properly studied, by Maria Gatto and her team. This is also a very rich rock art site, located in a small, “hidden” valley at the south side of the wadi. There are depictions of ibexes, donkeys, gazelles, cattle, ostriches, a few giraffes and elephants, a single hippo and an amphibian. And hunting figures (archers) are sometimes associated with the wild fauna. More than 20 boats represent some of the most prevalent images depicted. These and most other images belong to the Predynastic period. Importantly, at the location there are two gueltas, or pools that become filled with water during occasional heavy rainfall. The specific location and the nature of the rock art has led Gatto and team to suggest that it may have been a site for elite hunting, but also of great ritual significance in the Predynastic period.

There is limited destruction by modern quarrying at CAS-6, as well as problems with dust from the heavy trucks passing by, but CAS-2 is still in very good condition. This is not the case at rock art site CAS-7, which is located just 500 m from the Nile. This site shows Middle Kingdom boats and various animals, but has been almost obliterated by both ancient (Roman?) and modern quarrying.

In addition to these three known sites, there are numerous other rock art sites along the wadi. Many are small, with a few animals only; others comprise dozens of images.

Generally, this type of Predynastic and later rock art is well-known, both along the Nile and in the Eastern Desert. Hence, with a possible exemption for site CAS-2, it is not unique, but of tremendous importance for understanding the use of Wadi Abu Subeira over the last 6.000 years.

Ancient stone quarries

Last, there are numerous ancient quarries of generally unknown age along the wadi. None of these have been properly published, but have been briefly communicated at conferences. Several were spotted at the time when QuarryScapes were part of the survey of the wadi (2006-2007).

Like in the Palaeolithic, the quarriers took advantage of the silicified sandstone or quartzite, especially along the northern side of the wadi. They made hand-held grinding stone, typically oval or boat-shaped, and there are remains of quarry activities both along the slope and on the “escarpment”. A few extensive quarry sites have been seen, but most are almost “hidden” among the boulders and stones that have tumbled down the wadi slope. There are also remains of ornamental quartzite quarries, but what was actually procured is not known.

The quarrying in Wadi Abu Subeira must be seen in connection with the extremely widespread, similar quarrying of quartzite in the Aswan region as a whole, especially in the area around Wadi Abu Agag south of Subeira and on the West Bank (Gharb Aswan). At the west bank grinding stone was procured in the Late Palaeolithic and then again – in massive amounts – from the Predynastic to relatively recent times. Aswan was indeed a big supplier of grinding stone to all of Egypt for 3.000 years, from roughly the Old Kingdom to the Roman period. Aswan is also renowned for its ornamental stone quarrying, of which quartzite was an important commodity, especially in the New Kingdom, but also in the Roman period.

Sandstone for building purposes was also quarried at Subeira in ancient times. Most traces of the production are no destroyed by modern quarrying, but there is reason to believe that there once were relatively substantial quarries on both flanks close to the mouth of the wadi (Gebel el-Hamman and Khattarah). This type of quarrying, especially for building temples, was widespread in the Aswan region in the Pharaonic and Graeco-Roman periods.

Thus, the quarrying at Subeira is a reflection of what was generally going on in the Aswan region through history – and prehistory.

The lowermost 10 km of Wadi Abu Subeira in 1965 (Corona satellite image) and in 2011 (Google Earth). Note the development of agriculture and clay mining (tracks and mines show up as light lines and spots).

Threats to the archaeology

The threats to the archaeology in general and the Late Palaeolithic rock art in particular are similar to most other places in modern Egypt: Expansion of villages, cultivation, stone quarrying, and mining activities. Egypt still experiences strong population growth; hence there is a need for more housing and agriculture. Expansion of infrastructure and industry follows, and thus quarrying and mining expand, especially in the desert areas bordering the Nile Valley. Subeira is located exactly in this, from an archaeological perspective, heavily threatened border zone between the valley and the desert.

Village and agricultural expansion

The mouth of Wadi Abu Subeira was inhabited 200 years ago and probably also much longer back in time. In first half of the 20th century there was no particular development at the wadi mouth, but in the 1950s and 60s, in the era of construction of the High Dam at Aswan, the cultivated area was expanded and a canal built from the Nile to feed the fields. Since then cultivation has expanded about 4 km into the wadi. Khattarah and Makla villages by the mouth (on the south side) has also greatly expanded over the last 40-50 years, and since the 1960s a new village has been built close to a side valley (Khor el-Usina) on the north flank, about 1.5 km from the Nile.

The expansion of agricultural fields has now reached to the dam protecting from flash floods, and there may not be immediate risks from further expansion of cultivated areas. Also, the giving of new concessions for land cultivation appears to have stopped in Suebira. However, within these areas, as well as in the villages, there will, naturally, be changes also in the near future. Generally, the lowermost 4 km of the wadi is now so affected by modern development that there is little archaeology left to preserve at its floor. At the flanks, however, there are still many sites; CAS-6 with its Palaeolithic rock art is a testimony! And, importantly, the mouth of the wadi is of particular significance for understanding the geomorphology of the wadi – how it developed in the Late Palaeolithic and later. In other words: the mouth is the important place for finding out whether Wadi Abu Subeira was a “fjord” at the time the Late Palaeolithic rock art was made. To find out, one way to proceed is to investigate the old sediments by digging and drilling within the agricultural zone (but, of course, also higher up in the wadi).

Rock art (on the cliff) among spoil heaps from modern stone quarrying in Wadi Abu Subeira: Adel Kelany on his way down from inspecting part of rock art site CAS-7 (Pharonic rock art). Photo: Per Storemyr

Stone quarrying

The ancient sandstone quarries by the mouth of the wadi have been “reactivated” over the last 40-50 years. One reason is that there has been a ban on using Nile silt (traditional mud brick) for house building at least since the High Dam at Aswan was finished by 1970. This is because silt is no longer deposited: The building of the first dam at Aswan around 1900 and later the High Dam implied the cessation of the annual flood downstream of the dams. Thus, people reverted to stone for building their houses. Consequently, legal and illegal small-scale stone quarrying has been going on along the Nile throughout Egypt. But this is “artisan” quarrying, to some extent following age-old traditions. It damages archaeology, and has done so at several places in Wadi Abu Subeira (also by CAS-6), but it is not as destructive as larger-scale, fully legal building stone quarrying: A very big quarry has developed over several decades in an area of 1 square km at the north side of the wadi mouth (Gebel el-Hamman). The quarrying has, in practice, destroyed almost all archaeology (very probably also Palaeolithic rock art).

Small-scale quarrying is very difficult to control and thus may still pose a minor risk in the lower reaches of the wadi. The same is true for the large quarry at the mouth, which may, at some stage, wish to expand.

Subeira: A lonely stone with Predynastic rock art and a modern clay mine in the background. Photo: Adel Kelany

Clay or tafla mining

Aswan clay (Egyptian: Aswan tafla) is famous and has a tradition for pottery production since several thousand years. This is not clay from the Nile, or Nile silt, which was generally the main source for pottery in Ancient Egypt, but various types of very fine-grained rocks, deposited as layers within the Nubian sandstone. Hence, Aswan clay must be mined to be useful for pottery and other forms of ceramics and, consequently, the Aswan region abounds in smaller or larger holes in the bedrock since it is often easier (or more economic) to procure the clay by underground as opposed to open-pit mining.

With the industrial expansion since the 1952 Revolution, production of ceramics also gained in importance and so did Aswan clay. But it seems that Wadi Abu Subeira was opened up for clay mining only some 15-20 years ago, intended for the general ceramics industry, as well as for lining in high-temperature furnaces. According to satellite images (Google Earth), there were few clay mines in 2002. From then on the mining greatly expanded to about 40 individual operations by several, mainly private companies, but also the state-owned El Nasr Mining Company. However, the development has come to a virtual standstill over the last couple of years. This is thanks to the conservation efforts by Adel Kelany and his MSA team (see below). Some of the clay is used for brick production and there is a small factory (furnace) at the south side of the wadi, about 5.5 km from the mouth. It was constructed between 2005 and 2007.

Since the clay mining is going on underground, existing mines have limited impact on archaeology. But when they were opened, they heavily altered the landscape around the mine openings because there was a need for both access tracks and for depositing non-useful rock taken out from the shafts. Thus, there are big spoil heaps around each mine. And the network of tracks laid down on the wadi floor certainly has an impact on fragile archaeological sites, such as ephemeral camps.

Clay mining also takes another, specific form in Wadi Abu Subeira, just as it does along the entire Nile Valley. Since there is no more any annual Nile flood to leave fertile silt on the fields, people have found other ways of getting their cultivated areas fertilised not only by chemical means: They go up on the hills along the Nile, dig up clay and silt from the bedrock in small, open pits and transport it back to the fields. It is an ecological, though work-intensive, way of replacing the former Ethiopian silts brought by the river with a natural, domestic product, present in unlimited quantities. And it is probably also used for construction purposes. Virtually uncontrolled, the only trouble is that this “quarrying” endangers archaeological sites, also in Wadi Abu Subeira – in particular Palaeolithic tool workshops on top of the escarpment at the north side of the wadi. However, it seems that there is now little expansion of this “home industry” and it may not pose any great risk at the moment.

These are the greatly expanding iron mineral (hematite) mines in Wadi Abu Subeira. Source: Google Earth (2011)

Iron mineral mining

Aswan iron ore is also a famous commodity and, as we have seen, may have been in use as far back as the Palaeolithic. It was procured for red pigment throughout the Pharaonic period, and later (then perhaps also for iron-making), but we only know of one large mine in the region from these times; it is located at the West Bank, just opposite the Island of Elephantine. Modern mining started with the industrial expansion in the 1950s, especially just to the east of Aswan City in the Wadi Abu Agag area. It was meant for sustaining a national steel industry, but due to the relatively low-grade iron ore, most of the mining ceased in the 1970s and was relocated to the Bahariya oasis in the northern part of the Western Desert, from where a railway was built to connect with the steel plant at Helwan near Cairo.

Over the years there have been many attempts at revitalising the iron mining in Aswan, but with limited success, as seen from the perspective of the steel industry. However, red pigment (hematite) can also be obtained from the iron deposits; it is used, for example, for the paint industry and as a concrete aggregate. On Google Earth the slow expansion of the mines in the Agag area can be followed from 2002 and at this time there were also a few signs of exploitation about 12 km up in Wadi Abu Subeira, some 7-8 km north of Agag.

Since then this iron mineral mining has greatly expanded in Subeira, but it was not until recently that the great risks it poses to archaeology became fully realised. The operations are now undertaken by 2 companies and goes on as large-scale, open-cast mining, since it is not economically viable to carry out underground mining. Thus, big areas have already been totally altered and potentially important archaeology may thus have fared pretty bad.

Contrary to the clay mining, which is controlled by the Aswan Governorate that is obliged to report to the regional antiquities authorities (MSA), iron mineral mining is under the jurisdiction of the Egyptian Mineral Resources Authority (EMRA), a part of the Ministry of Petroleum. EMRA does not have to to report new mining/quarrying concessions in “deep” desert areas to MSA, but only those concessions that relate to areas near the Nile Valley. Wadi Abu Subeira is considered “deep” desert, and thus it was only by chance that it was recently found out that there are plans for greatly increasing the iron mineral exploitation in Subeira. Several concessions have been given, covering a huge tract of land along a 10 km stretch of the wadi (see maps). If operation begins within these concessions it may be the death to some 75% of the archaeology. Three Late Palaeolithic rock art sites are also within the concessions.

Clearly, the reporting practices of EMRA is a huge problem, since there is, of course, much archaeology in the “deep” Egyptian deserts! As leader of the Ancient Quarries and Mines Department of MSA, Adel Kelany is now working on changing these practices.

This picture is symbolic for the good cooperation there has been between the Egyptian archaeologists and the clay mining industry in Subeira until now. Photo: Adel Kelany

Conservation efforts

Fortunately, following very recent contacts between MSA and EMRA, there are indications that EMRA may go back on a part of the concessions, changing them so that they are not touching known archaeological sites. For the part of the wadi that has already been roughly surveyed, there are few problems for Kelany and team to draw up reasonable maps, handing them over to EMRA for inspection so they can alter the concessions. However, around the ongoing iron mineral mines, survey has hardly begun and thus very rapid work is now necessary in order to save as much archaeology as possible also in this area. It should be rather clear that the ongoing iron mining should not expand, at least not until the area is thoroughly surveyed.

The strategy followed in this particular conservation effort is not to stop iron mineral mining in the desert district east of Aswan, but to relocate it to areas with little or no archaeology. The same strategy has been followed by Kelany and his MSA team for the clay mines. In the course of the last few years they have worked very closely with the clay industry and the Governorate and so been able to prevent opening of new mines in Subeira. New concessions have, however, been given in another wadi to the south of Subeira (near Wadi Abu Agag). This wadi has been surveyed and displays limited archaeological remains. The same strategy has been followed in another work by MSA Aswan, the protection of the ancient granite quarries close to the city centre. Many modern quarries, which formerly destroyed the archaeological remains, are now relocated to other areas.

Another important conservation strategy followed over the last few years has been to hire local guards for controlling the most important archaeological sites in Subeira, primarily the Palaeolithic rock art sites. At CAS-6 there has also been put up a simple fence in order to show that this is archaeological ground.

Current nature protectorates in Egypt. Could Wadi Abu Subeira enter this list? Source: Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency

Future protection

With the legal basis provided by the Egyptian Antiquities Law (no. 117/1983), the current conservation regime aims at “spot protection” of important archaeological sites, thus allowing mining to go on immediately beside the archaeology, but banning new operations. Given the specific history and geography of Egypt, 117/1983 has not been an inefficient law, and many archaeological sites have been saved on its basis. Until now Subeira is also a good example of this (given that the iron mining can be controlled and relocated).

However, with the tremendous pressure on land resources in Egypt, the trouble with “spot protection” according to 117/1983 is that landscape and connections between archaeological sites are not properly taken into account. The context of the archaeology is, in other words, not being pursued. This has for quite some time been realised on the international arena and in many other countries, and, accordingly, new laws have been issued. This topic is also discussed in Egypt.

Until new laws are being issued, one way to protect larger tracts of landscape is to bring law no. 102/1983 into play. This law is for nature protectorates, of which many have been declared in Egypt over the last 20-30 years, indeed. Some nature protectorates are large, some are small, some enjoy good protection, some not – but often they have in common that they also provide a means to secure the context of the archaeology within their boundaries. In many cases archaeology has thus been protected without the Egyptian state even knowing it is there.

Subeira may be a candidate for protection according to law 102/1983. For many people it may seem that the landscape is so thoroughly “industrialised” by mining that there is hardly any “nature” left. However, it is important to recall that Subeira is 60 km long, very little disturbed in the upper reaches and there is even no proper road through the wadi (there are asphalt roads in many other wadis in Upper Egypt). Moreover, the current mines, though numerous, are not entirely altering the overall landscape. All this stand, in fact, in quite some contrast to many other substantial wadis entering the Nile Valley from the Eastern Desert, especially in the Aswan Governorate. Moreover, it may well be that the flora and fauna of Subeira is richer than we usually anticipate. Only further studies can give an answer to this.

Thus, Subeira – and first of all its unique, irreplaceable and immovable Late Palaeolithic rock art – deserves many further seasons of hard fieldwork, and consideration in view of a possible landscape protectorate. It may not only be a big chance to protect the rock art and the archaeology as such, but also to save one of the few, relatively undisturbed tracts of beautiful desert land bordering the Nile Valley in the Aswan region – a region that greatly relies on the income from tourists. In the future they won’t necessarily travel to an entirely industrialised region, but they will certainly keep coming if they can admire, in addition to temples and tombs, beautiful desert landscape – and the oldest rock art in North-Africa.

Despite modern activity, Wadi Abu Subeira, here seen towards west, is still a place with Upper Egyptian desert beauty. The stone lines in the foreground belong to an ancient trap for hunting. Photo: Per Storemyr

A vision – World Heritage Site

Returning to the fantastic group of Late Palaeolithic rock art sites in Upper Egypt – Qurta, el-Hosh and Subeira – it should be kept in mind that Qurta is already visited by tourists and described in major travel guides. This shows that there is considerable public interest in this very special archaeology. And one can also look to the extremely popular Palaeolithic rock art in Europe! What is more; Qurta has been discussed in terms of nomination as a World Heritage Site. Clearly, all the three sites deserve World Heritage status – it is just this kind of unique archaeology that UNESCO initially thought of as belonging to the heritage of all mankind. Thus, the similar rock art in the Côa Valley and at several places in France and Spain are since long designated as World Heritage Sites.

So a vision may be that Qurta, el-Hosh and Subeira were pursued for nomination as one World Heritage Site. There is a very long way to go in Subeira, for first of all much fieldwork is needed to assess the full potential of the rock art and other archaeology. Simultaneously risks have to be mitigated and a proper management regime established. Then a possible nomination procedure can follow. This is not only World Heritage, it is also very fragile heritage. It needs to be handled with the utmost care!

…and also the current rock art in Subeira is a testimony to what is really important for people. (But the truck looks so old? Could it be Late Palaeolithic? The Flintstones? Answer: It is the dust from the clay mines that sets in the pecked outlines and so is responsible for the patination…) Photo: Per Storemyr

Sources

Personal communication

This article has been written in close cooperation with Adel Kelany, and we thank Dirk Huyge for providing much information and for comments. Thanks also to Mindy Baha El Din for input on nature protection.

The Late Palaeolithic rock art at Subeira

- Kelany, A. In press. More Late Palaeolithic rock art at Wadi Abu Subeira, Upper Egypt. Annales du Service des Antiquites de l’Egypte.

- Kelany, A. Submitted. The archaeological excavation and survey at the Unfinished Obelisk and Wadi Subeira. Papers from the conference: The First Cataract: One region – Various Perspectives. Berlin, September 2-5, 2007.

- Storemyr, P., Kelany, A., Negm, M. A., Tohami, A. (2008). More “Lascaux along the Nile”? Possible Late Palaeolithic rock art in Wadi Abu Subeira, Upper Egypt. Sahara, 19, 155-158. PDF (0,5 MB)

- Kelany, A. Survey work at Subeira. Unpublished reports to MSA (formerly SCA) in 2008, 2010 and 2011.

Predynastic and later rock art at Subeira

- Gatto, M., 2009. Egypt and Nubia in the 5th–4th millennia BCE: A view from the First Cataract and its surroundings. British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan, 13: 125–45. PDF from British Museum

- Gatto, M., Hendrickx, S., Roma, S., Zampetti, D., 2009. Rock art from West Bank Aswan and Wadi Abu Subeira. Archéo-Nil 19, 151-168. View online at academia.edu

- Gatto, M. et al. 2009. Archaeological Investigation in the Aswan-Kom Ombo Region (2007―2008). Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo, 65: 9-49. View online at academia.edu

- Lauwers, R., 1995. Egypt: Rock art in danger. BCSP (World Journal of Prehistoric and Primitive Art), 28: 10.

- Mayer, W., 1981. Felszeichnungen bei Assuan. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo, 37: 313-314.

- Červiček, P., 1974. Felsbilder des Nord-Etbai, Oberägyptens und Unternubiens. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag. (Includes information from the DIAFE VIII expedition by Leo Frobenius. Photos and drawings from Subeira are online at the Frobenius institute. Simple search using: wadi abu subeira)

- Murray, G. W., and O. H. Myers, 1933. Some Pre-Dynastic Rock-Drawings. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 19: 129-133.

- Chester, G., 1892. On Archaic Engravings on Rocks near Gebel Silsilah in Upper Egypt. The Archaeological Journal, 49: 120-130.

Wadi Kubbaniya and Middle Palaeolithic occupation at Subeira

- Wendorf, F., and R. Schild (eds), 1989. The Prehistory of Wadi Kubbaniya 2-3. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press.

The Late Palaeolithic rock art at Qurta, and general about rock art in Egypt, a small selection

- Dirk Huyge, Dimitri A.G. Vandenberghe, Morgan De Dapper, Florias Mees, Wouter Claes and John C. Darnell, 2011. First evidence of Pleistocene rock art in North Africa: securing the age of the Qurta petroglyphs (Egypt) through OSL dating. Antiquity, 85, 330: 1184–1193. Abstract

- Huyge, D., 2009. Rock Art. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles. Read online

- Huyge, D., 2008. Côa in Africa: Late Pleistocene rock art along the Egyptian Nile. INORA – International Newsletter on Rock Art 51, 1-7. Read online

- Huyge, D., Aubert, M., Barnard, H., Claes, W., Darnell, J.C., Dapper, M. de, Figari, E., Ikram, S., Lebrun-Nélis, A., Therasse, I., 2007. “Lascaux along the Nile”: Late Pleistocene rock art in Egypt. Antiquity 81. Read online

History of “quartzite” stone quarrying in the Aswan region, with special emphasis on Gharb Aswan

- Bloxam, E., Heldal, T. & Storemyr, P. (eds.) (2007): Characterisation of complex quarry landscapes: an example from the West Bank quarries, Aswan. QuarryScapes report, Geological Survey of Norway, Trondheim. 275 p. PDF (20,2 MB)

Modern development and conservation

These reports deal with ancient quarries and Egypt as a whole, but there are relevant chapters on threats to archaeology, and conservation in the Aswan region:

- Storemyr, P. (2009): Whatever Else Happened to the Ancient Egyptian Quarries? An Essay on Their Destiny in Modern Times. In: Abu-Jaber, N., Bloxam, E., Degryse, P. & Heldal, T. (eds.): QuarryScapes. Ancient stone quarry landscapes in the Eastern Mediterranean, Geological Survey of Norway Special Publication 12, 105-124. PDF (4,1 MB)

- Storemyr, P., Bloxam, E. & Heldal, T. (eds.) (2007): Risk assessment and monitoring of ancient Egyptian quarry landscapes. QuarryScapes report, Geological Survey of Norway, Trondheim, 207 p. PDF (12,8 MB)

Nature Protectorates in Egypt

Previous posts on this website

- Wadi Abu Subeira, Egypt: Palaeolithic rock art on the verge of destruction

- The Late Palaeolithic rock art at Qurta, Egypt: Field season 2011

- The Late Palaeolithic rock art in Wadi Abu Subeira (Egypt)

Maps

The map shows:

- Green: Rough outline of archaeological sites, including Late Palaeolithic rock art

- Dots: Selected archaeological sites

- Red: Modern stone quarrying (some places discontinued).

- Red triangles: Spots of modern clay and iron mining, greatly intensified since 2010-2011

- Blue: New concessions for iron mining

Two maps almost 200 years apart. Subeira as mapped in Description de l’ Egypte, vol. 6, Atlas Géographique, p. 20, Planche 2 (Source: Bibalex), and by the Egyptian General Survey Authority in 1991 (from map sheet NG36B3b Aswan, width of field c. 13 km)

Pingback: Ep. 005 - Meanwhile, In Egypt... | The Maritime History Podcast

Pingback: Palaeolithic rock art at risk: New discoveries in Wadi Abu Subeira, Upper Egypt | Per Storemyr Archaeology & Conservation

Pingback: A Palaeolithic, life-size Nubian ibex carved on rock: Adel Kelany with new discoveries in Wadi Abu Subeira, Upper Egypt | Per Storemyr Archaeology & Conservation

Pingback: Ep. 005 - Meanwhile, In Egypt... | The Maritime History Podcast

Following this and a previous blog post, there have been several stories in the media on the potential destruction of the Subeira rock art, and also a news story in “Nature Middle East”, see here: http://www.nature.com/nmiddleeast/2012/120513/full/nmiddleeast.2012.73.html.